THE

CLUSTER

PARADOX

‘Cluster’ has surged frighteningly in the national lexicon during the Covid-19 crisis. But, as it turns out, the larger they’ve loomed, the more reassured we can be.

Become a Stuff supporter today for as little as $1 to help our local news teams bring you reliable, independent news you can trust.

Contribute Now

Watching the number of New Zealanders infected in our coronavirus clusters blossom, then spread through the country like blood through our veins can feel deeply worrying.

One friend has turned those figures into something of a comfort blanket: each day he updates a spreadsheet he maintains to track each cluster.

He’s got the right idea. Sort of. Because all those statistics we hear about our clusters should be deeply reassuring, says Professor Shaun Hendy, director of Auckland University’s Te Pūnaha Matatini centre. It means we are still in control. For the most notable thing about our clusters is how much we know about them.

Auckland University's Shaun Hendy says we should be reassured, not alarmed, by what we know about the coronavirus clusters.

Auckland University's Shaun Hendy says we should be reassured, not alarmed, by what we know about the coronavirus clusters.

Countries like the US have gone far beyond the point of tracking and encircling their clusters. We could have reached that point if we had developed a sudden, huge cluster, such as the one in South Korea where 500 cases exploded from a single church meeting. Our contact tracing system would have been overwhelmed, our capacity to ring-fence the cluster gone.

“It can be alarming to look at the clusters and see so much detail about them,” says Hendy, “but other countries are so well beyond the point of looking at clusters any more.

“If the disease did get out of control here, we would very quickly lose the ability to trace those clusters. The fact we’ve seen them and are able to have a really good description of them is showing that … we are on top of it.”

As Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said at one of her media briefings, the clusters “tell us something helpful” - where the disease came from, how it spread and to whom. Linking every case in a cluster to an ‘index patient’ - the source - gives health officials confidence they have contained the spread and not missed branches.

It’s the cases that aren’t attached to clusters that cause concern - where did they come from? Hendy says what clusters don’t tell us is the “low-probability stuff”: do we have chains of asymptomatic people who haven’t been tested, and who could be essential workers?

Dr Harriette Carr, the deputy director of public health, says clusters generally follow a clear pattern.

Dr Harriette Carr, the deputy director of public health, says clusters generally follow a clear pattern.

Dr Harriette Carr, the deputy director of public health, says our big clusters (barring those in rest homes) have mostly followed a shared pattern: a ‘seed event’, where one person has infected another 15 or 20, usually in situations involving alcohol, and lots of repeat close contact over a long period of time. Then those 20 people go home to unwittingly infect workmates and colleagues.

From studying our clusters, says Carr, officials have learned that in New Zealand, there’s two degrees of separation, and Kiwis are very mobile. Because symptoms begin gradually, people hadn’t realised they were sick until after they’d started spreading infection. And, they’ve confirmed, sticking to our bubbles works: one cluster had an unexpected post-lockdown branch caused by some illicit bubble-bursting.

Officials also discovered something about, well, our willingness to lie to public health officials.

“People aren’t always honest about who their close contacts are - and you can have the best contact tracing in the world but if they aren’t honest, or forget, we can only go so far,” says Carr.

We’ve come across various reasons why people aren’t honest - I can leave it to your imagination - but some of it is illegal activities.

It’s too early, Hendy says, for science to give a detailed description of the environment that Covid-19 would best thrive in. But New Zealand’s five biggest clusters have come at a school, a wedding, a pub, a conference and a rest home. If, say, a month ago you had pressed Hendy to predict where our clusters might be, he probably would have picked those sorts of locations.

Actually, he would also have expected some at major events, like rock concerts or sports fixtures. We’ve been lucky in that regard, he says. Lucky too, not to have one overwhelmingly large cluster like the South Koreans (though our spread-out population will have helped).

Infectious diseases usually create clusters of infection. A cluster is defined as a group of 10 or more cases with a common cause.

Mapping those clusters could be done for all such illnesses - for example, with seasonal flu, but because it is less deadly, and we have a vaccine, no one bothers. It is done when we get outbreaks of measles, which is much more infectious than Covid-19 and occasionally fatal. It was done with SARS in 2002 but was much easier because people with SARS all had very strong symptoms.

What we know is that on average, each person with coronavirus will infect between two and three others. But some won’t infect anyone, and some will infect many (so-called “super spreaders”) - leading to a huge range of outcomes. All cases in New Zealand are imported - that is, they should link back to someone who caught the virus in Europe, China or the US then returned here with it.

We have 16 major clusters in New Zealand, with the five biggest being Marist (the school, in Auckland), Bluff (the wedding), Matamata (the pub), Hereford (the conference, in Queenstown) and Rosewood (the rest home, in Christchurch). Here’s what we know about them.

MARIST

Stephen Dallow, chair of the board of the 700-pupil Auckland Catholic girl’s high school, has said the index patient of Marist’s Covid-19 cluster might never be found.

On the Ministry of Health’s website, the source of the Marist cluster remains listed as ‘unknown’. And while, clearly, the original source of the Marist outbreak must be someone who had travelled overseas, Dallow’s assertion may indeed be right, says Hendy.

However, he says, some interesting work is going on that may shed more light on the Marist cluster - and all of New Zealand’s big outbreaks. The RNA (ribonucleic acid, which carries the virus’ genetic information) of Covid-19 randomly mutates over time into different strains, meaning it should be possible to identify which strain each cluster was infected with and give some hints as to its origin.

Most cases in the Marist cluster are actually now outside the school.

Most cases in the Marist cluster are actually now outside the school.

That should allow researchers to add previously isolated cases into clusters, and give them much more confidence about linking cases rather than presuming that fleeting, unmemorable encounters transferred the infection.

Every little piece of information adds to the confidence that we understand the chain of transmission that led to the disease.

The Marist cluster began when a teacher tested positive for the virus on the weekend of March 22-23, and as our graphics show, it grew rapidly. Among those infected were students, teachers and the school’s principal, Raechelle Taulu, before it spread into the wider community. Ministry of Health data shows that apart from a few cases in Canterbury, the cluster never really spread beyond Auckland - and mainly the city’s North Shore and inner suburbs.

The majority of cases in the Marist cluster, says Carr, are actually no longer among the school community itself, but in attached households. Likewise in the Bluff and Matamata clusters, the number of cases among people who weren’t at the pub or the wedding exceeds those who were.

In the Marist outbreak, there were several events which may have helped transmission: a social gathering of teachers, a school fiafia night on March 14, and a multi-school theatre production.

It’s likely that the virus moves differently through a school community compared to other clusters. There’s evidence young people don’t show such strong symptoms and are not as infectious as older people, and they are less likely to fall seriously ill or die. That could make the cluster harder to track, because it is less visible, but at the same time, in a semi-enclosed community like a school, mass testing is more viable.

Marist certainly showed up the limitations of the ministry’s contact tracing, who took three weeks to interview one student who was a close contact of an infected teacher. “It was too little, too late,” says the student’s father. His daughter, fortunately, was not infected. “It’s the biggest cluster in the country - and it takes three weeks to get hold of people.”

Cases: 93 Fatalities: 0 Recovered: 83

BLUFF

It was the perfect setting: a restaurant perched atop a hillside with sweeping picture-window sea views. It was also the perfect setting for an infectious disease: two large families from different parts of the country converging in one location.

“Weddings are that kind of event,” says Hendy.

“People come from around the country, around the world - it’s one of the reasons why we enjoy it, quite apart from celebrating someone getting married, it’s a great chance to catch up with people we haven’t seen for a long time.”

So the nature of the event is … it generates a lot of risk.

The reception was at the Oyster Cove restaurant, at Bluff’s Stirling Point. But the Bluff Cluster is actually mis-named, because the wedding itself was actually in Invercargill. And the wave of infections it caused travelled the country, all traced back to the wedding on March 21 - when gatherings of under 100 people were still permitted.

In part, that was because while the couple both lived and worked in Invercargill, their family roots were from further afield: the groom from a Wellington Greek family (12 Bluff cases were reported in the capital), the bride from a Waikato whanau (where 28 cases were reported). There were also cases from this cluster recorded in the Hutt Valley, Nelson-Marlborough, Northland and Waitemata (Auckland North) regions. Both bride and groom were among those infected.

Oyster Bay restaurant: the 'seed event' for the Bluff cluster.

Oyster Bay restaurant: the 'seed event' for the Bluff cluster.

Oyster Bay venue director Ross Jackson said afterwards he’d been hesitant about hosting the wedding, but had taken extra precautions. Guests greeted each other with elbow touches and waves, not hugs and handshakes. Later, Jackson said, “in hindsight, if we knew then what we know now, we probably wouldn’t have done it”. The bride later said: “We feel lots of responsibility, but everyone has been really reassuring.”

The index patient in this cluster is believed to be a man in the groom’s party, an Air New Zealand flight steward who had flown back into the country a few days earlier.

Flight crew were under no obligation to self-isolate. On the day, it seems the man was asymptomatic. The day after the wedding, the steward was seen gargling salt water - popularly touted on the internet as a coronavirus ‘cure’ - but he explained this was because of a tooth problem.

A statement provided by the airline said the man was “deeply upset by what has happened and the implication in comments published in the media that he did anything wrong."

From there, the virus’ tentacles spread. Fitting Harriette Carr’s model, one branch spread among Invercargill City Council employees - where the bride works. Also employed there, it has been reported, was the wife of Alister ‘Barney’ Brookland. The Invercargill grandfather died at home of Covid-19 on April 14 and has been confirmed as part of the cluster.

The other death was that of the groom’s father, 87-year-old Christo Tzanoudakis, a former docker and chip shop owner and senior member of Wellington’s Cretan community. He passed away at Wellington Hospital on April 10, having fallen ill five days after the wedding.

Cases: 98 Fatalities: 2 Recovered: 65

MATAMATA

The Redoubt Bar sits on the main street of the prosperous Waikato town of Matamata, in the shadow of the ‘Welcome to Hobbiton’ sign. Wednesday March 17 was St Patrick’s Day, and New Zealand’s pubs were still open (they would remain so for another four days). The Redoubt was serving pints of green Heineken, the staff wore green top hats and a live band played.

New Zealand’s third biggest Covid-19 cluster was about to form.

St Patrick's night at Matamata's Redoubt Bar began a cluster that has grown to 76 cases.

St Patrick's night at Matamata's Redoubt Bar began a cluster that has grown to 76 cases.

Ten days later, the bar posted on Facebook that this “insidious awful virus” had led to a confirmed case among one of its staff members.

At the time, of course, going to the pub was a normal part of life. Hendy says: “A situation where you are in close proximity for a long period of time - maybe in close physical contact, such as people putting their arms around each other, probably having conversations close to each other so they can be heard over the noise - it’s definitely a very dangerous situation.”

The Matamata cluster, says epidemiologist Arindam Basu, associate professor at Canterbury University, shows the ‘network effect’ at play. Imagine, he says, the two of us meet in his office and he’s infected, but doesn’t yet know it. We shake hands, he passes on the virus, and I go on to shake hands with three other colleagues. We now have a network of five, with Basu and I separated by one degree, and Basu and my friends by two degrees (everyone in a cluster should have one or two degrees of separation).

Canterbury University epidemiologist Dr Arindam Basu.

Canterbury University epidemiologist Dr Arindam Basu.

The job of a contact tracer is to trace these networks, understand how they connect into the cluster, and to track the superspreaders who join networks together.

In the early part of the Matamata outbreak, their network was the Redoubt: all the original cases either attended the bar, or were close contacts of those who had. The effect of a lockdown is to disrupt the inter-connection of networks.

The Matamata cluster did not travel far: 73 of the cases were in the Waikato DHB region, and three in the neighbouring Bay of Plenty and Lakes (Rotorua, Taupo) regions. Carr says that’s partly because those originally infected were typically locals, who took the infection home with them, and because lockdown came quickly after and prevented a wider spread.

Clusters like these are likely to be harder to track, especially as the moment of infection can be so casual and forgettable. Germany’s first major cluster, in Munich, was traced to an infected employee at a car parts company visiting from Shanghai. Electronic diaries helped them follow the transfer of the infection from the woman to the staff she met with in Munich, but the transmission from the fourth to the fifth case, whom she’d never met, was tracked to a shared salt cellar in the staff canteen.

The Matamata cluster’s death was recorded on April 16, when a man in his 90s died in Waikato Hospital. His family members were unable to be with him due to government restrictions.

Locals have flooded the bar’s Facebook page with messages of support, and some posted pictures of hearts on its locked front door. Not until Level 2, at least two weeks away, will New Zealand’s bars and pubs be able to re-open.

Cases: 76 Fatalities: 1 Recovered: 48

ROSEWOOD

The Rosewood rest home, a 64-bed specialist dementia home in the Christchurch suburb of Linwood, is the largest of five clusters linked to rest homes - and inevitably has been the most deadly of the major clusters.

The Rosewood rest home - exactly the sort of place you don't want an infectious disease cluster to form.

The Rosewood rest home - exactly the sort of place you don't want an infectious disease cluster to form.

So far, 10 deaths have been linked to the Rosewood cluster.

Coronavirus studies overseas have shown age alone is a predictor of a worse outcome. Age plus a ‘co-morbidity’ (that is, an existing serious medical condition such as diabetes, or heart or lung problems) makes it even worse.

And Carr says dementia patients are even more vulnerable: it is very hard to isolate them, very hard to swab them for testing and hard to get them to self-report symptoms.

You don’t want this cluster to form at all.

Actually, says Hendy, the surprise is we didn’t see more rest-home clusters - we’re fortunate that we had early-warning signs from overseas and were able to take precautions quite early on, such as physical distancing and limiting visitors to homes.

Again, the ingredients are there: lots of close physical contacts between lots of people, and lots of them having other conditions so likely to suffer more from the disease.

Carr says the ministry is now conducting tests of every resident in a rest home where they have even a single coronavirus case, and treating those single cases as potential clusters.

Authorities made the decision to transfer Rosewood patients to Burwood Hospital.

Authorities made the decision to transfer Rosewood patients to Burwood Hospital.

The first reported case at Rosewood was on April 3. When its cases reached 28, the split was reported as being 15 staff and 13 residents.

Every resident in the hospital’s dementia unit was thought to have been exposed, and all 20 were moved to a surgical ward at Burwood Hospital. A nurse working on the ward told Stuff they feared none of the 20 would survive the virus.

The first death came on April 9, a woman aged 90 - New Zealand’s second coronavirus death. A day later, 78-year-old former boxing coach Bernard Pope became the second Rosewood resident to pass away. Since then, a man in his 60s, two men and three women in their 80s, a man in his 90s, and a man in his 70s have also died.

Cases: 52 Fatalities: 10 Recovered: 15

HEREFORD

The quadrennial World Hereford Conference is, says the World Hereford Council, a “key date in any Hereford breeder’s calendar”. The 2020 edition drew breeders of the beef cattle worldwide to Queenstown from March 9 to 13.

The 400 delegates from 18 countries enjoyed pre- and post-conference tours of both islands - and were told by the Ministry of Health they were free to continue sight-seeing even after one conference attendee had tested positive for coronavirus after returning home to Australia.

Among those who subsequently became infected was a coach driver who had driven delegates around, a Lincoln University student, and people who had attended the Wanaka A and P show alongside the breeders. Of the Hereford cases, 23 were patients in the Southern DHB region. There were also cases recorded in Canterbury, South Canterbury, Wairarapa, Mid-Central (Palmerston North), Counties-Manukau and Waikato.

Like the wedding and the bar, this cluster ticked the boxes: a large group of people together in one place for a long period; most likely in a quite noisy environment, causing them to speak loudly and closely.

Again, says Hendy, it was “the kind of contact we would always have said would be risky…”.

The combination of the Bluff and Hereford clusters caused an unusual pattern in our coronavirus infections: As at 2:20pm on April 24, the Southern DHB had the most coronavirus cases of any district health board, some 216 - despite having only about four per cent of the population.

Queenstown was, unsurprisingly, the first location for random community testing.

Queenstown was, unsurprisingly, the first location for random community testing.

It’s no coincidence that the first round of random community testing was held in Queenstown despite the Queenstown-Lakes district having only around 39,000 permanent residents. It was an insurance measure to check these two big clusters had not grown beyond the reach of contact tracers.

Cases: 40 Fatalities: 0 Recovered: 39

THE SLOWDOWN

There are two key statistics about the clusters that can offer some comfort.

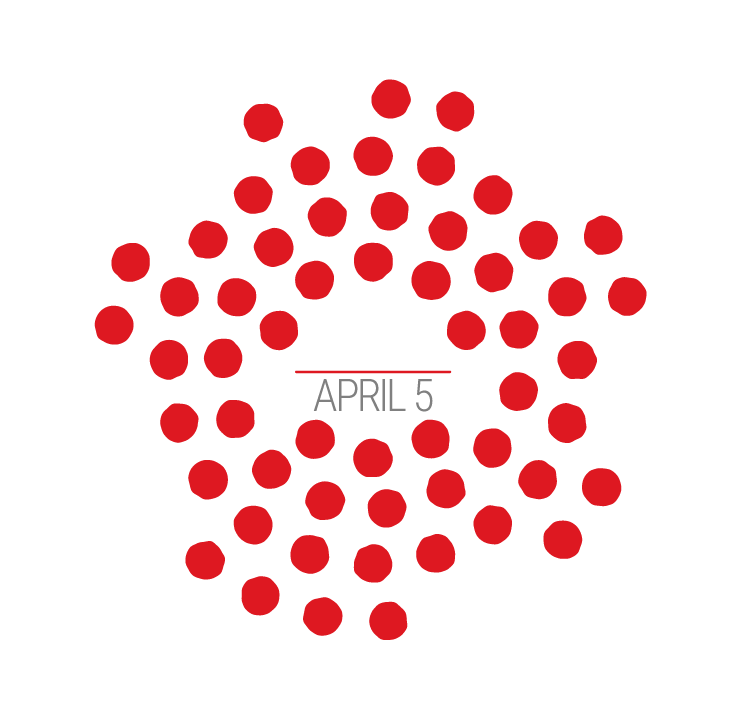

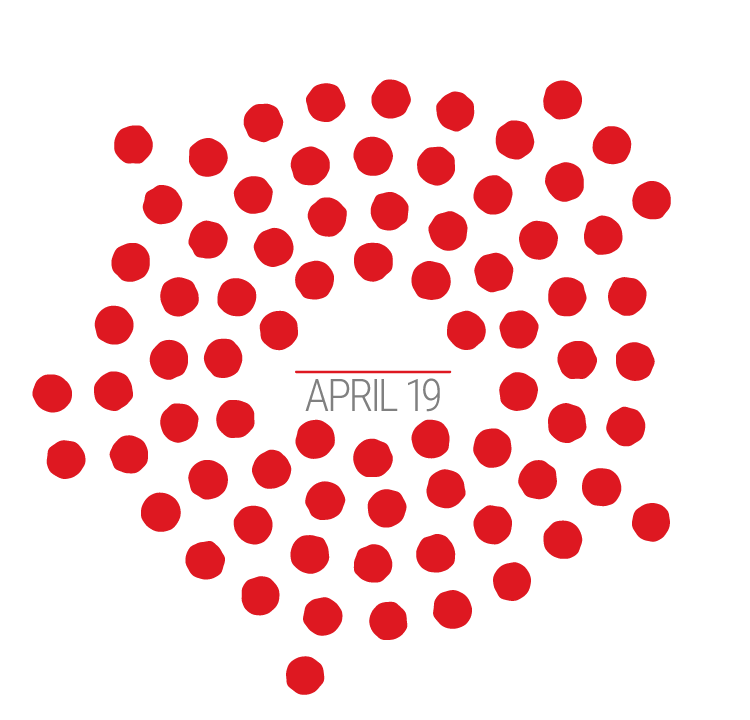

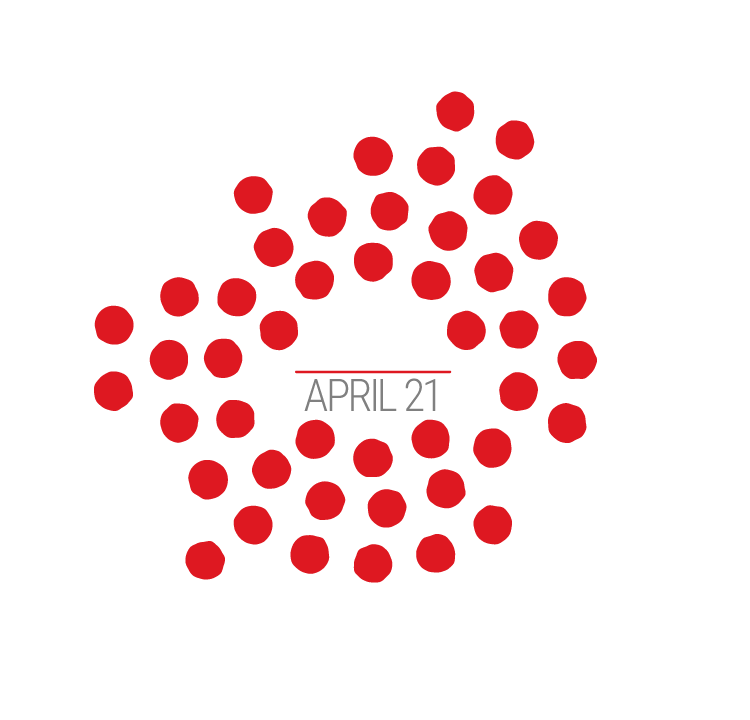

The first is the way their growth - once rapid - has slowed and even stopped.

The Marist cluster, for example, took 12 days to jump from 19 cases to 84. But only one new case was recorded in the week to Wednesday April 22. Similarly, Matamata saw only three new cases in that time, and Bluff, which grew by 81 cases over 15 days, saw just nine in that week.

On Saturday, April 25, the ministry declared one of the 16 significant clusters - the Boomrock wedding in Wellington - closed, as there has now been two incubation periods (28 days) since a case.

"We expect more clusters to be closed in coming days," the ministry said in a statement.

The curves are flattening on New Zealand's clusters

The second is the rise in the number of cases attributable to clusters. That means there are fewer unexplained infections, which means a growing confidence that the clusters have been effectively identified and ringfenced.

Three weeks ago, major clusters accounted for 20 per cent of all cases; two weeks ago it was 33 per cent; now it is 40 per cent of all cases.

And if you want extra reassurance: if we were in another country, then the different ways of measuring infection could mean our clusters would have been reported as much smaller.

Carr says we have developed one of the broadest ‘case definitions’ in the world. It means cases which might have been disregarded have been picked up, analysed and added to our statistics. For example, people reporting a runny nose (who might be dismissed elsewhere) are tested, even though they have a low probability of being infected.

With Covid-19’s reproduction number now down to 0.48, Basu says we won’t see numbers now “explode” in the way the Marist and Bluff clusters did. But he notes, “if there were no restrictions on people’s movements, then clusters would form very rapidly across the country.”

It’s not impossible, Basu says, once we get more freedom of movement, that we will see new clusters form - it depends on how far elimination has progressed. “My guess is we have reduced it, but not all the way.”

Carr says it all depends on whether every case has now been identified, or whether there are a few that have slipped the net. “If we can track and manage those, there’s a good chance it won’t happen. It’s whether we’ve been able to do that - that’s the million dollar question.”

There’s always a chance we will be surprised, agrees Hendy, and there remains a risk another cluster will form. But what we should all do, he says, as we move towards level 3, is take some lessons from the big five clusters on how to behave.

“[They] illustrate some of the risk factors if we do go to level three or level two, to do as much as we can to avoid the situation that has occurred in those clusters,” he says.

“It is a really good lesson for us as we step down the lockdowns and move away from our more controlled situation. Everyone should take a look at those clusters, and think about the risks you are taking when you go back to engaging with other people.”

Data: Andy Fyers

Reporting: Steve Kilgallon

Design: Aaron Wood

Animated map: John Harford

Editor: John Hartevelt