soldiers inc.

Chapter Two

mortal danger

The rich rewards of private military contracting come alongside the very real risk of death.

Gary ‘Slash’ Brandon survived tours in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere with enough cash to retire at 40, but without his right leg.

Gary ‘Slash’ Brandon felt a slight cramp in his left leg. He lifted it from the floor of the armoured truck as he drove through the Iraqi desert, and wiggled it slightly to ease the pressure. At that moment, a remote-detonated bomb exploded beneath the car’s engine.

When Brandon came to, about ten seconds later, plumes of dust were rising from the sand, he could see the desert floor through the holes in the truck, the front windscreen was blown out and the soldier in the front passenger seat was unconscious.

He felt as if someone had jammed a hot poker up his spine. He screamed in agony, then remembered he had a client in the back seat and checked he was alive. The front-seat passenger regained consciousness, and with both legs broken, was dragged screaming from the truck. Brandon still couldn’t move. He couldn’t feel anything in his right leg, couldn’t lift it.

As his comrades took him from the vehicle, a fellow soldier assured him he would be fine. Later, he would tell Brandon he’d seen shattered bones protruding through his skin.

Months later, Brandon would have that leg amputated. He feels lucky though: that moment of cramp in his other leg probably saved him from being a double amputee. And that meant, despite what he had suffered, he could return to the private military contractor circuit once again, forging a second career in Afghanistan.

Brandon, like most of the private contractors in Iraq in 2006, was there to provide close protection services to overseas officials, corporate warriors and key workers in the nation’s reconstruction.

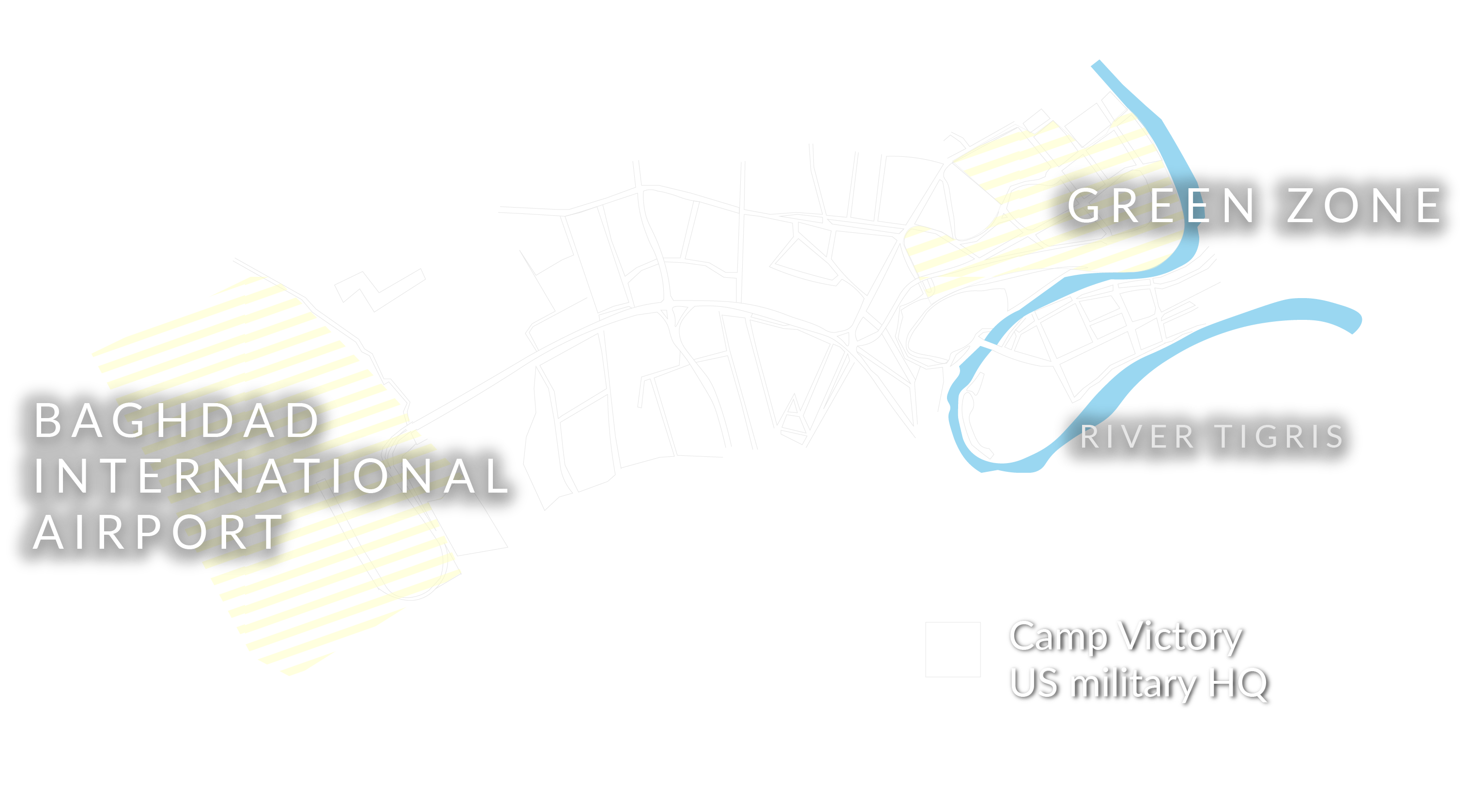

That meant lots of ‘missions’, or transport movements. And many of those were along Route Irish, which in 2005, the Sydney Morning Herald declared the world’s most dangerous highway: “a terrorist’s gift, a ready-made shooting gallery in which there are few dud ducks.”

The 12km stretch of road linking Baghdad International Airport and the ‘Green Zone’ - the guarded downtown area of the Iraqi capital where the foreigners encamped - was symptomatic of the dangers of Iraq. Around every corner there could be an IED (improvised explosive device), a suicide bomber, or a sniper.

Iraq was the hot ticket for those on the Circuit. It paid better than Afghanistan and promised more excitement, but it arguably came with much more risk.

Most who drove along Route Irish would cop some stray bullets from people firing from the rooftops. Eventually, it led the private military companies (PMCs) to swap partially-armoured vehicles for fully armoured. Even then, the roofs remained soft, making driving beneath bridges an uneasy experience.

Monty Gurnick Jr, a former soldier, prison guard and policeman, was on his first trip along Route Irish after arriving in Iraq to work for ArmorGroup when his convoy was hit. During his stint in Iraq, convoys he was travelling in were hit three times on the route.

Gurnick describes seeing huge, smoking craters and burned out vehicles, and admits he would get nervous before setting out. “You would get guys who would complain - why are we doing so many missions today? Why are we going back there?

Gurnick talks calmly about his ‘contacts’.

He was in the middle vehicle in a convoy hit by an IED which exploded beneath the engine. Two utes of insurgents drove across the sand towards them, firing. He fired back until they retreated, while his colleagues destroyed their damaged vehicle, so it couldn’t be used by the enemy.

On another occasion, his vehicle was hit on the left-front tyre, shredding the rubber. They were able to continue on ‘run flats’, a harder plastic inner tyre. A crowd had been preparing to attack them.

Gary Brandon had served a ten-year stint in the army from 1986, where he learned to parachute, and left to become a professional tandem skydive instructor in Taupō.

Eight years after that, in March 2004, he joined the exodus to Afghanistan. A friend was working for a PMC called Global Strategies Group, which had a security contract for the upcoming parliamentary elections, and gave Brandon a reference.

He found himself in Chaghcharan in the central province of Ghor, 8500ft above sea level, working in a two-man team inspecting security plans for polling stations. The locals, he says, were “awesome, really friendly”. The main issue was a bit of local banditry.

At the end of the contract, he went home wanting more. He was back less than three weeks before he was gone again - waiting until his first wife was away for the weekend before signing up to a contract working security on the main checkpoint into Baghdad International Airport.

Again, he says, there was very little action: A suicide bomber who blew himself up but fortunately nobody else; a sniper who fired from a row of abandoned houses, who Brandon responded to with a half-magazine of bullets.

It was on his next contract, in Tikrit, 140km north-west of Baghdad, where Brandon’s luck ended. In September 2005, he signed on to a contract with ArmorGroup. The US Army was gathering up old ammunition stores left from the first Gulf War and detonating them, to prevent them being seized by insurgents. Brandon’s team drove long distances between the munition sites, checking them all for security risks.

Their camp was frequently targeted. In seven weeks, they had six near-misses, one on Christmas Day when an IED exploded just to the side of their vehicle. It was the seventh that got Brandon.

He says now that they must have been under surveillance by the insurgents, who would have remotely triggered the device by cellphone, aiming to kill the ‘client’, knowing he was a passenger in Brandon’s vehicle. Maybe, he says, the command came slightly too early: a fraction of a second later, it would have exploded beneath the cab and they would “have all been jelly”.

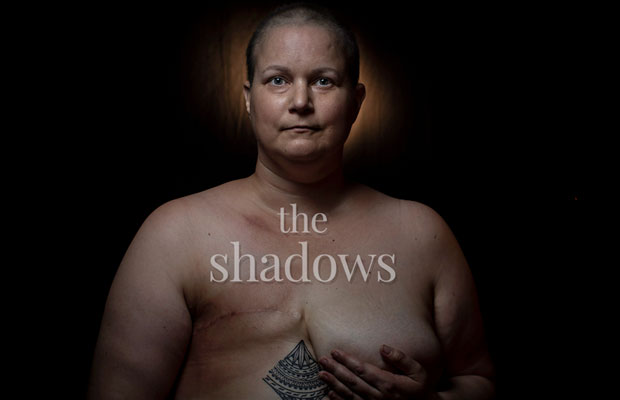

Gary Brandon escaped death, but his friend Teina ‘Narms’ Ngamata did not.

Academic Maria Bargh, who has researched the world of the Circuit, says she found no official record-keeping of New Zealanders killed while working as private military contractors. Only news reports provide a partial record.

The first to die was an engineer, John Robert Tyrell, killed in an ambush in Kirkuk, Iraq, in May 2004.

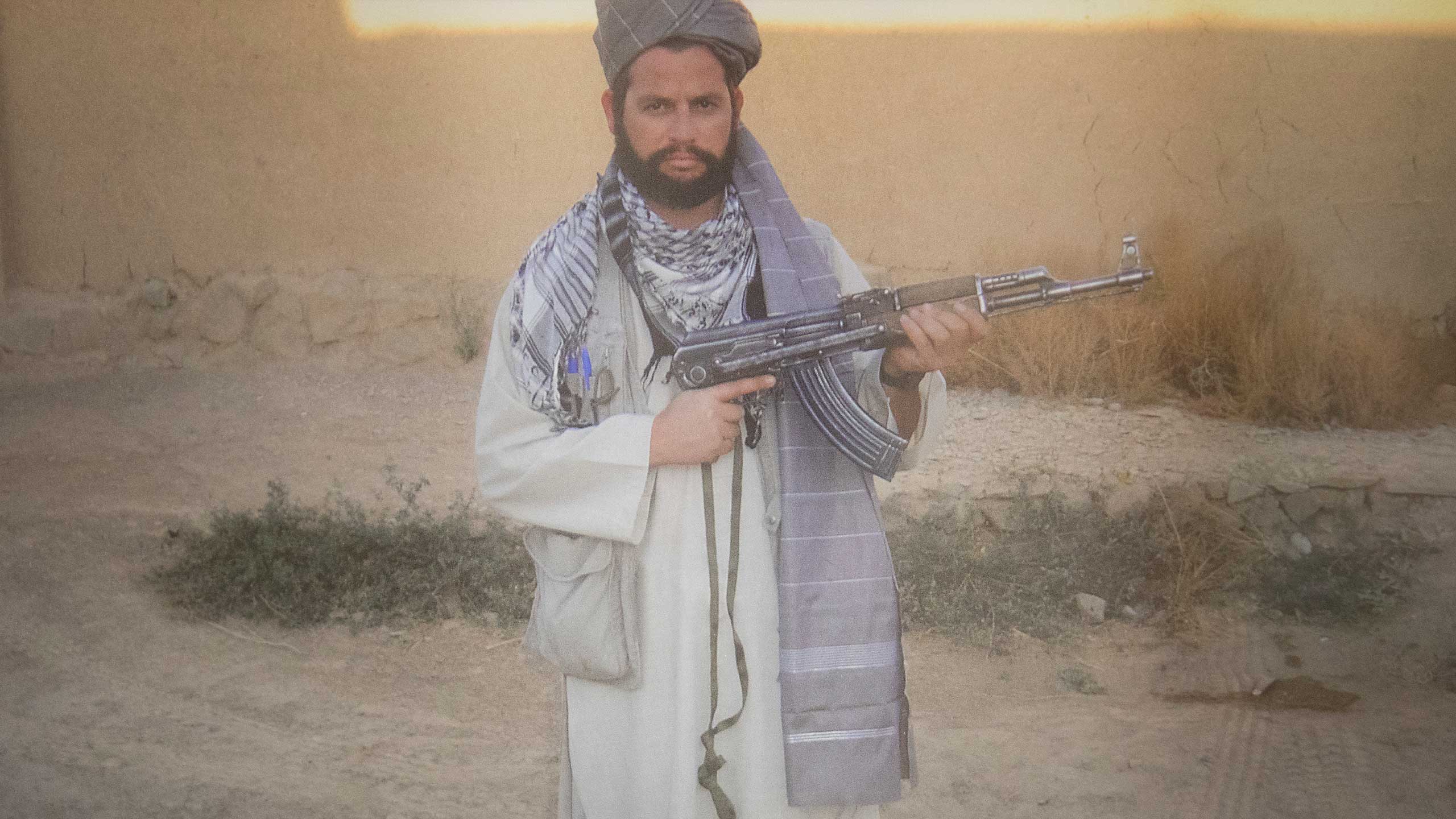

The first killed in a military role was most likely Ngamata, a Rarotongan-born former soldier who was driving a truck in Iraq, on the same contract as Gary Brandon. A photo of Ngamata with his colleagues in Iraq hangs on the wall of Brandon’s garage.

Teina Ngamata

Teina Ngamata

The next casualties were Darryl ‘Dip’ De Thierry, who was also blown up while driving a truck in a convoy in Iraq, and an Australian-based New Zealander, Kelly Clark, who died in Afghanistan in 2010 when a truck he was a passenger in crashed after hitting a patch of ice. Steve Gilchrist was killed when an armour-piercing shell hit his vehicle as he escorted a truck convoy.

Darryl De Thierry

Darryl De Thierry

The website icasualty.org tracks PMC deaths. It records 4897 deaths in Iraq, and 3892 in Afghanistan. The majority were Americans. It says 11 New Zealanders died in Afghanistan, but doesn’t log any of the deaths in Iraq.

A year after his death, Ngamata’s widow, Cheryl, told the Waikato Times that they always knew there was a danger, but “you don’t think it will happen to you.”

She was talking after the death of De Thierry.

“If you think about it too much,” Gary Brandon says, “you won’t get out of bed in the morning. So it’s just ‘let’s do it boys’. ... That’s why they are paying us the big bucks.”

Brandon tells a story of how another Kiwi he knows became nicknamed the ‘Baghdad Bodyboarder’ after a bomb blew up the car he was travelling on, killing the others inside. His door was blown open and off its hinges, and he was thrown on to it, with the door surfing off into the desert and taking him to safety.

It’s when he’s asked if he considers himself lucky that Brandon proffers the detail about the cramp in his left foot. While the client in the back seat suffered with terrible nightmares and was soon evacuated home, for Brandon, there was no post-traumatic stress.

He thinks getting knocked out immediately saved him from seeing anything that would have triggered it.

![]() Read

Read

Chapter 1

Soldier X, who worked as a PMC in Iraq and Afghanistan, says he didn’t experience it either, but reckons he’s an outlier. “I feel guilty that I enjoyed these situations when not everyone does … [but] I accept it is just how I am wired.”

While the regular military provide compulsory counselling after major incidents, the private military world does not. Monty Gurnick says only once was he offered a psychologist after a contact. Instead, he’d return, alone, to his room, and think about what had happened.

“The hardest thing for me was being in my room,” he says, with emotion.

“Thinking about my kids. And although I came home safe, it still weighs on the mind. I could have left them. That could have been me that day, and they would’ve been without a dad. Yeah.”

Clinical psychologist Ian de Terte, who was a senior police detective, is now a senior lecturer at Massey University and has consulted to the military.

“PTSD in an environment like Iraq or Afghanistan is quite helpful,” he says. “What I mean by that is you need to be hyper-vigilant, you need to be aware of what’s going on around you, because if you’re not, you will die. It becomes a problem when you’re in transition, when you come back to normal life.”

Or as Monty Gurnick puts it:

De Terte says the counter is that you need to be able to switch off when home. American military personnel, for example, drive extremely fast for safety in combat zones, then come home and drive the same way on regular roads.

“You’ve got to take some responsibility for your own mental health ... these contractors are pretty much on their own. It’s not like the police or the military when they go overseas: they’ve got psychologists with them, and they have to check up when they get home.”

De Terte says the fact contractors can sign up for another tour almost immediately would also have an impact. A period to re-adjust to regular life is helpful.

De Terte says some people will get PTSD and some won’t. Research suggests 90 per cent of us will experience some sort of traumatic event in our lives, but we don’t all get PTSD.

“And some people can encounter a lot of traumatic events, and these people are probably more de-sensitised to these incidents. I would suggest you always want to stay sensitised to things, but it is hard to do.”

Gary Brandon’s right heel had been blown apart inside his boot. It left a big hole where his calcaneous bone ought to have been. So they cut a section of his instep, and rotated it, reattaching his heel, then grafting skin from his groin to the sole of his foot.

He says a side-effect was pubic hair growing on his sole. The damage to his heel meant he had nothing to balance his weight on in the back of his foot.

After ten days in Germany, he was flown home to New Zealand, where he spent a further month at Middlemore Hospital in South Auckland.

When they decided to amputate, the conversation with the surgeon was brief. He remembers the date his leg was lost: November 6, 2006. It was his decision, he says, but he really had little option. There were still gaping holes in his tibia.

Within four weeks, Brandon had his first prosthesis. Remarkably, he returned to professional tandem parachuting, and did another 300 jumps with his prosthetic limb. That’s even more remarkable given he had undiagnosed breaks in two vertebrae (his second wife, Bex, is a doctor, and discovered those injuries herself).

But then he went back for more.

He had been offered a new job, as a team leader in northern Iraq, but despite his medical clearance, the job fell through when they heard about his leg. Instead, he signed up for a maritime security course, run by another New Zealander, Brian Tuki.

At the end of the course, Tuki offered him a job in Saudi Arabia, on the Kuwaiti border, working inland escorting clients back and forth from oil tankers. He ended up as the project manager.

It was fairly uneventful, but it got him back on the Circuit. From there, he got a security gig in Afghanistan, working alongside trainees for President Hamid Karzai’s security team. He left after six months, following a disagreement with his boss. But the company agreed to honour his ticket home, set for two months ahead, so he found work in Kandahar, negotiating with local Afghan companies to supply gravel and road barriers.

Kandahar was rough, Brandon says, with suicide bombers, nail bombers and random street shootings, but it worked for him. When the Americans hit trouble and left town, Brandon stayed and set up in partnership with one of those left short, making “quite a bit of coin”.

It was now October 2010, and Brandon had made enough to be comfortable. He wanted to get back to his new wife. Since then, he admits, he’s hardly worked. Every five years, he gets a lump sum payment in US dollars until he reaches the age of 76. “I’ve been looked after real good,” he says.

Regrets? None, he says. If he still had his limb?

“F….. if I know. Probably would have still been there [on the Circuit].

“I wanted to spend more time back here,” he says. Then he admits: “But, yeah, you do miss it.”

Credits

Words

Steve Kilgallon

Visuals

Chris McKeen

design and development

Sungmi Kim

Editor

John Hartevelt

Additional visuals

Monique Ford and Joe Johnson

With thanks to Ben Stallworthy and Scott Cottier