Thirty-seven years ago, Allan Woodford walked out the door of his home in the middle of the night and disappeared forever. The case has confounded his family and the police ever since. Did Woodford take his own life? Or was he murdered? Michael Wright reports.

This story is featured on Stuff’s The Long Read podcast. Check it out by hitting the play button below, or find it on podcast apps like Apple Podcasts, Spotify or Google Podcasts.

Anyone who knew Allan Woodford knew that he liked to keep his own company. He’d turn out to watch his sons play rugby, and was good for a couple of beers in the pavilion afterwards, but that was about it. He rarely entered a pub, or a shop, or attended any social event at all. His family is pretty sure the only weddings he ever went to were those of his own children.

Woodford lived to be outdoors. Hunting was his passion. He worked for the Pest Destruction Board, shooting rabbits on farms around Mossburn, in northern Southland, and in his spare time hunted just about anything else. Deer were a favourite. Mossburn is known as the deer capital of New Zealand and Woodford spent untold hours in the hills around the town and the nearby Tākitimu Mountains stalking his favourite game. It was widely agreed that any stag that had the misfortune of coming into Woody’s sights didn’t stand a chance.

Friends and family would later describe Woodford as solitary, rather than anti-social. If you called at his home on Bedford St — and plenty did — he was always welcoming. He was popular among the farmers on whose properties he worked and was always happy to yarn and have a laugh. “Northern Southland’s Barry Crump,” as one put it. Woodford was no bush philosopher but he did have a roguish charm. When a local farmer used the rugby ground opposite the Woodford home to prep his dog for dog trials, Woody fired off a few shots from a slug gun in their direction. There was no serious danger, but the pellets sent the poor collie haywire. The farmer couldn’t work it out.

Family, though, was at the centre of Woodford’s social life. He and his wife Jean had eight children and, in time, 22 grandchildren. Woodford, nearing retirement, doted on all of them.

So it was a shock to everybody when, in the early hours of April 20, 1985, Allan Woodford disappeared without a trace. Some time before sunrise that day he got out of bed, walked outside and vanished. In 37 years, there has been no sign of him. His family has no idea what happened.

Allan Gordon Woodford was born in Dunedin in 1920. As a young man he was a champion cyclist. “A. Woodford has ridden very consistently all the season,” the Evening Star observed in July 1939, “and thoroughly deserves the most points’ medal [sic].” Around this time, he met Jean Stout, also from Dunedin, who was impressed by the young cyclist. “Mum was a cycling groupie, I guess,” their daughter Kerryn said. The couple married in 1940.

In the early 1940s Woodford was based at a military camp near Dunedin, preparing to head off for war, when the government called for men to stay home and work in essential services. Married, and with two children already, Woodford volunteered. He spent the next 14 years working in a coal mine in Nightcaps in western Southland. The family moved to Mossburn in 1957. Woodford would spend the rest of his working life outside.

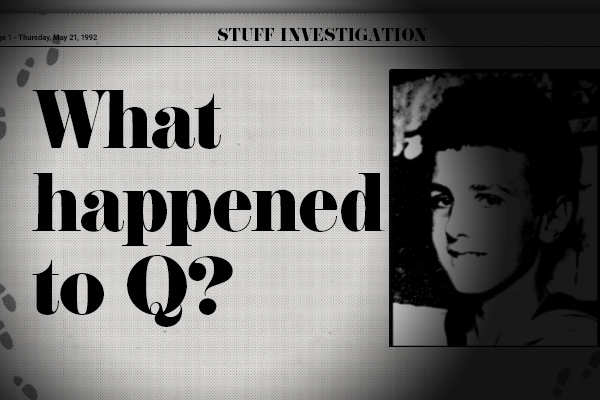

One of the last photos taken of Allan Woodford before he disappeared in April 1985.

One of the last photos taken of Allan Woodford before he disappeared in April 1985.

The Woodfords settled into life in Mossburn. They lived in a house supplied by the Pest Destruction Board, and raised their family. Their seventh and eighth children arrived after the move. In 1977, the house burnt down in an accidental fire, and they built a new home on the next-door section: a quaint, A-frame structure, painted a shade of green best described as of its time. Next to the house was the garage, where Woodford kept his rifles, ammunition, tools, and all the odds and ends an outdoorsman would accumulate. At the back of the property was a hut where friends of his sons, now moving into adulthood, would often stay, usually before a hunting trip of their own. On the next-door section, owned by the Pest Destruction Board, was another shed, where Woodford parked his truck.

The house on Bedford St, Mossburn, from where Woodford disappeared.

The house on Bedford St, Mossburn, from where Woodford disappeared.

As adults, several of the Woodford children built their own lives in Mossburn. This required their father to expand his social network, if only a little. Along with the rugby-watching, he now had to travel across town to see them. On the evening of April 19, 1985, a Friday, that was exactly what he did. On a pushbike, the former champion cyclist, now 65 years old, called at three of his sons’ homes. The conversation was, as usual, mostly about hunting: Heading out tomorrow? Where? Who with? His last stop that night was to see his son Mark, who lived only a few doors down on Bedford St. He left about 9.30pm.

Woodford himself had no hunting plans for Saturday. He hoped to do some work on the conservatory in the house, but he was also expecting two of his granddaughters from out of town. He was excited about the visit and made a point on Friday of getting bikes out of the garage for them to ride. The girls’ mother, Kerryn, was Woodford’s daughter. She had married a farmer from a different part of Southland and her husband’s rugby team was playing Te Anau that day. The plan was to drop the girls in Mossburn, en route to Te Anau, and collect them after the game.

The last person to see Allan Woodford alive was his wife, Jean. They watched TV together until about 11pm, then went to bed. They slept in single beds in an upstairs bedroom and during the night Jean heard her husband get up and then return to his bed. She presumed he’d gone to the toilet. She heard nothing else before she woke at about eight o’clock the next morning and found her husband was gone.

Jean Woodford around the time of her husband’s disappearance.

Jean Woodford around the time of her husband’s disappearance.

At first, Jean, a placid woman, wasn’t worried. No one was. Woodford’s truck was in the driveway. His guns were in place, as were his boots and all his outdoor gear, so wherever he was, it couldn’t be far. He hadn’t even taken his tea-cosy hat, which he wore everywhere.

Kerryn and the girls arrived in Mossburn about 10am. “Your father’s missing,” Jean said to Kerryn, but the mood was still more puzzlement than panic. Kerryn drafted in Mark, and together they searched the paddocks behind Bedford St. At worst, they thought he might have walked away from the house and had a heart attack, or fallen into a ditch and broken his leg.

There was no sign. They canvassed all the neighbours. Nothing. Even then, nobody was terribly concerned. Woodford was a family man with everything to live for. He had a wife, a retirement to enjoy and deer to shoot. The idea that he would vanish without a trace was so alien to the family that none of them seriously entertained it. Kerryn left for rugby in Te Anau. When the match was over she called home and learned that in the meantime Jean had rung Woodford’s friend Jack Orlowski, a police officer who lived in Invercargill. Jean only wanted to ask if he knew where Woodford might be, but when Orlowski heard his friend was missing, he was concerned enough to drive straight to Mossburn and help organise a search. By now, it was mid-afternoon. People were starting to worry.

Kerryn caught a ride back to Mossburn, where Orlowski and Lumsden cop Constable Bob Gibson had taken charge. With the help of some locals, they scoured the town and several kilometres in every direction. It turned up nothing.

“The next five or six days are just a blur,” Kerryn says. “We went out searching every day … just kind of in a limbo of looking, looking, looking. Everywhere we could possibly think of.”

The search for Allan Woodford began in earnest the day after he disappeared. It would be coordinated by Orlowski and at least one other officer from Invercargill. That day, Sunday, April 21, 100 people assembled at Mossburn fire station. Volunteer fire chief Jim Guyton had spent the previous evening ringing around the district for volunteers. Farmers and station owners sent as many men and vehicles as they could.

“They came from everywhere,” Guyton says. “[The police were] blown away that we got that many people overnight. That’s the beauty of a small district. And Woody was known. Shit, everybody knew him.”

Former Mossburn volunteer fire chief Jim Guyton helped organise a search for Woodford the day after he vanished.

Former Mossburn volunteer fire chief Jim Guyton helped organise a search for Woodford the day after he vanished.

Search parties were dispatched, including one by air. The town was divided into five sections and the surrounding countryside into 14. Road verges were a priority, in case Woodford had gone for an early morning walk and been hit by a car. After that, instructions were to visit every house, speak to all occupants and search every building, hedgerow and shelter belt in the area. As much as possible, farmers and farm workers were allocated their own properties, or other land they knew well. Police involvement only lasted the weekend, but the volunteers kept it up for another week.

Some areas searchers paid particular attention to. One was a place called Waterloo, about 10km west of Mossburn, in the Tākitimu Mountains. Woodford knew the area well. He had a hut at Waterloo he used for hunting. But there was no sign of him at the hut, and no sign anyone had been there. Another area of interest was Black Ridge, a densely wooded outcrop in the southern foothills of the Eyre Mountains, just north of Mossburn. It was another area Woodford knew, but, perhaps more importantly, it was the closest bush you could walk to from town.

One of the enduring puzzles of Woodford’s disappearance is how he managed to so utterly vanish. It’s one thing to disappear if you live in a city, with an entire urban landscape on your doorstep and hours or even days before your absence is noted. It’s another to do it in a tiny rural town, in the middle of the night, and take nothing with you. Searchers surmised that if Woodford had managed the latter he might have taken the shortest route into the bush.

‘Shortest route’, however, was a relative term. Mossburn sits on an alluvial plain next to the Oreti River, which runs from mountains near Queenstown to Invercargill on the south coast. The flat farmland surrounding the town is crisscrossed by fences. Black Ridge is about 5km away and Waterloo about 10km, but only if a traveller is determined to move in a straight line, which would mean crossing paddock after paddock and hurdling countless obstacles. “Bloody ditches and electric fences,” Woodford’s son Mark says, “You’d have a bastard of a time.” Both places were more easily accessible by road, which almost doubled the distances and increased the likelihood of being seen. Waterloo was probably a six-hour walk from Mossburn. If Woodford had managed that, he would have made at least part of the journey in daylight.

“It didn’t make sense to us,” Kerryn says. “Why the hell he’d walk when he could have taken his Land Rover is really weird.”

The organised search lasted about a week, but the family continued looking for several more. In a way, they never stopped. “We hunted and hunted and hunted,” Woodford’s son Donald says. “It drives you mad.” “You’re always looking,” Mark says, “[but] you give up the initial search … because you don’t know where the hell to go.”

They were at a loss. Woodford’s three-year-old grandson, Sam, used to spend all his time with his grandfather, following him around as he did chores. Everyone was telling him grandad was ‘lost’, so Sam figured he just had to wait until grandad was found. Every day, he sat in a chair, waiting. He didn’t know how to play otherwise.

About this time, the family says, two police officers paid them a visit. Bev Woodford, Mark’s wife, remembers they had a single purpose: to close the case as a suicide. “[They] said, ‘Look, we’re terribly sorry about your father and everything, but the mind just snaps and they just go away.’”

Sitting in the lounge of Mark and Bev Woodford’s home in Bedford St, the same house Allan Woodford made his final visit to the night before he disappeared, three of Woodford’s eight children consider their father’s fate. From a framed black and white photograph on the wall above the TV, the protagonist surveys the scene: Woodford, sitting on the porch at Waterloo hut, wearing a wide-brimmed hat instead of his usual tea cosy. A Jack Russell, Utah, is on his lap.

Allan Woodford on the porch of the hut at Waterloo, in the Tākitimu Mountains. Utah is on his lap. SUPPLIED

Allan Woodford on the porch of the hut at Waterloo, in the Tākitimu Mountains. Utah is on his lap. SUPPLIED

The three children, Donald, 76 (3rd oldest), Mark, 71 (6th) and Kerryn, 66 (7th), agree there are four possible explanations for what happened to their father 36-and-a-half years ago. Three, really, once they discard, to considerable laughter, the idea that he abandoned his family to start a new life; perhaps shacking up with another woman and living out his days on the Gold Coast. “He’d barely been out of Southland or Otago,” Kerryn says.

One of the more plausible theories is dispatched almost as quickly – that Woodford went walking and suffered some misadventure: a heart attack, a fall, a hit and run. If this happened it would likely have been close to Bedford St, and, even if it wasn’t, it would not have been somewhere so out of the way that no trace of him could ever be found. “[If] he’d gone off somewhere,” Donald concludes, “we would have found him.”

That leaves two scenarios. One is suicide, which the siblings agree is possible. “I wouldn’t have thought in a million years he’d do anything like that,” Kerryn says, “but you don’t know what’s in someone's head.” But none of them really believe it. They think the last remaining theory is the most likely. They think their father was murdered.

Three of Allan Woodford’s eight children, from left: Mark, Kerryn and Donald.

Three of Allan Woodford’s eight children, from left: Mark, Kerryn and Donald.

John Turner is adamant Allan Woodford was killed, likely by more than one person.

John Turner is adamant Allan Woodford was killed, likely by more than one person.

The original police file included a lengthy report from Jack Orlowski. SUPPLIED

The original police file included a lengthy report from Jack Orlowski. SUPPLIED

Allan Woodford, left, and Jack Orlowski were old friends and hunting buddies. NZ POLICE

Allan Woodford, left, and Jack Orlowski were old friends and hunting buddies. NZ POLICE

A week before he vanished, Woodford reported to his boss at the Pest Destruction Board, John Turner, that he was losing petrol out of his truck. Someone was apparently sneaking onto the property at night, and siphoning the fuel straight out of the tank. Turner suggested he lock the vehicle – a novelty in the country – or, better yet, park it in the shed. It’s not clear if the truck was locked the night Woodford disappeared, but he had parked it in the shed.

John Turner is adamant Allan Woodford was killed, likely by more than one person.

Turner was Woodford’s friend as well as his boss. A week before he went missing, they had gone rabbit shooting together on Turner’s farm. When Turner heard what happened, his first instinct was foul play. He maintains that today. “I think someone’s gone round to pick up some petrol or something,” he says, “and I think at least a couple of people … knocked him on the head.” Turner is adamant on this point – that more than one person was responsible – because someone would have had to catch his friend by surprise.

Even at 65, Turner says, Woodford was stronger and more agile than men decades younger. He recalls one feat from that last rabbit shoot, when he was driving his truck through a creek. “There was a heap of young parry flappers [paradise ducks] on it,” Turner says, “and Woody said, ‘Don’t stop… Keep going… Now stop,’ and he went bang and he got the whole five or six in one shot. He threw the gun on the floor of the Land Rover, jumped out with his gumboots on, ran down to the river and collected the lot of them. If you asked your kid to do that they’d say, 'I don’t know if I can…' He was as fit as buggery.”

That the police never seriously entertained the homicide theory is a sore point for Woodford’s family. There was no scene investigation at Bedford St the day of the disappearance, no tracking dogs, no witness statements. Outside of the organised search, the only contact they had with police at the time was the detectives’ visit to declare the matter a suicide. Didn’t that piss them off?

Mark Woodford says police only conducted a cursory investigation into his father’s disappearance.

Mark Woodford says police only conducted a cursory investigation into his father’s disappearance.

“Shit yeah,” says Mark, “At the time we couldn't friggin' believe it but that was it…They never came round to the house and checked things out there. No police asked us anything at all.”

The family believe there was one reason for this – the sway of Woodford’s friend, Jack Orlowski. Orlowski, who died in 1989, was the cop who had helped organise the initial search but he came to wield far more influence in the case. That first weekend, he revealed that his friend had confided in him: if Woodford ever decided to take his own life he would do so privately.

“He has said to me,” Orlowski wrote in a later police report, “that if he ever wander [sic] off to die like an old elephant then no one will ever find him.” He went on to observe that Woodford had exhibited occasional signs of depression for about six months before his disappearance and had been deeply troubled by the plight of two of his older brothers, both terminally ill. “I feel that the subject … can not face the prospect of himself one day turning out like these two family members… I think that he has gone to some secret place probably not too far from home and there committed suicide.”

The original police file included a lengthy report from Jack Orlowski. SUPPLIED

This, Woodford’s family believe, was the sole reason police settled on the suicide theory. In a case with such a dearth of evidence pointing to anything, the statements of Orlowski, a police officer and one of Woodford’s closest friends, had a beguiling effect. “Dad’s biggest problem was he was mates with this cop and the cops did nothing,” Donald says. “That summed it right up.”

No one in the family had heard the “old elephant” theory, or knew of any health problems. But, they concede, it wouldn’t have been unheard of for a man of Woodford’s generation to disclose such things only to a mate. The sick brothers element, they have more trouble with. Woodford was second-youngest in a family of 13 children and both terminally-ill siblings were in their late 70s. Woodford was fit, and only 65. This year, all six of his surviving children will be older than he was when he disappeared.

Allan Woodford, left, and Jack Orlowski were old friends and hunting buddies. NZ POLICE

Allan Woodford was officially declared dead in 1992. Under New Zealand law, a missing person can be presumed dead after they have not been heard from for seven years. The coroner listed the cause of death as “unknown”. About this time, as part of the coronial process, the family gathered in the A-frame house Woodford disappeared from, for another meeting with a police officer. It did not go well. The officer had nothing to add and the meeting was little more than a courtesy. Kerryn lost her temper. “I said to him… ‘You’ve got no records, no investigation of any other sort. The police just assumed that he’d gone and done away with himself. You never looked at any other possibility. And now you’re telling me that it’s case closed?’ I said, ‘How can it be closed when there’s no resolution?’

“It’s like Dad didn’t even exist.”

Bedford St, Mossburn, in late 2021. The eastern facade of Woodford’s A-frame house is in the middle. The Tākitimu Mountains, one of the places searchers considered Woodford may have walked to to disappear, are in the distance.

Bedford St, Mossburn, in late 2021. The eastern facade of Woodford’s A-frame house is in the middle. The Tākitimu Mountains, one of the places searchers considered Woodford may have walked to to disappear, are in the distance.

Some time in the late 1990s, Detective Senior Sergeant Brian Hewett went looking for the police file on Allan Woodford. DNA was emerging as a crime-fighting tool and Hewett, head of the Invercargill CIB, wanted a sample attached to missing persons files for future reference.

But on the Woodford case, he came up short. He couldn’t even find a file. Hewett was pained. Though he joined the Invercargill police in 1986 – a year after Woodford disappeared – he had grown up in Mossburn and knew the missing man well. “He’s a nice fella, but he was a tough old fella,” Hewett says, “When we were kids around Mossburn we didn’t want to upset Woody.”

Today, police retain a thick file on the Woodford case. But almost none of it is what Hewett was looking for back in the 1990s. That file was lost. This one exists as a result of Woodford’s case appearing on the TV show Sensing Murder in 2010.

Sensing Murder was a popular, if dubious, staple of reality TV in the mid-2000s. Each episode was built around a cold case, usually a murder, and told the backstory of the crime and investigation before inviting two psychics to make pronouncements about what might have happened. Donald’s son, Glenn, contacted the producers about his missing grandfather.

“I didn’t have any faith in that programme,” Kerryn says. “They came and talked with us before the psychics came to see us. If they’d just brought the psychics up to meet us cold turkey … it probably would have been a completely different story.” As it happened, both psychics on the show were drawn to the family’s homicide theory – that Woodford went outside to confront someone and was attacked.

Sensing Murder wasn’t the family’s first encounter with clairvoyants. One day, only weeks after the disappearance, Bev Woodford arrived home with a friend to see a man staggering up the road with a divining rod. He had a pair of Woodford’s underpants slung over one arm and his electric razor over the other – presumably to help him commune with the missing man’s spirit. “We just lost the plot laughing,” Bev says. One woman traced Woodford to Black Ridge, where she identified his reincarnation in the form of a bumblebee. A few years ago another psychic approached the family, adamant Woodford’s body was at Waterloo – near his hut in the Tākitimu Mountains. Mark and Donald took him out there.

“He got out of the truck,” Mark says. “He was actually sweating. Sweat was coming off his face. [He said,] ‘He’s down there’... I had a broken arm at the time. Donald started digging. [The psychic] was friggin' sure we were going to find him. Donny dug for bloody bastard hours. There were some bloody good [fishing] worms there. I’ve been meaning to go back and get some.”

Donald is more circumspect. “You clutch at straws,” he says. “They say they can do something, you give it a try.”

Donald Woodford once escorted a psychic to Waterloo. The psychic was convinced his father’s body was buried there.

Donald Woodford once escorted a psychic to Waterloo. The psychic was convinced his father’s body was buried there.

Despite its obvious flaws, Sensing Murder generated a flurry of tips on the case. Police granted Stuff access to the file. The entries start in 2010, shortly after the episode first aired, and continue through to 2017. “Apologies for dumping this on you,” one officer wrote in an email that accompanied a lengthy statement from 2016, “I’m assuming Sensing Murder has been on TV again.” Another warned before a rerun that the telephonists at Invercargill police station should brace for a deluge of calls and any officers with light caseloads should prepare to be busy: “It really is a special time in one’s career when they get to contact all these people that ring in after Sensing Murder.”

Police could be forgiven their cynicism. The tips are a mix of the reasonable and the decidedly unreasonable.

“On Sataday morning I made a pendulum,” one begins, “And run it over the photoe the reaction i got was amazeing the pendulum took off spinning. I beleve ALLan WoodFord is berryed …”

Many, however, focus on one man. We’ll call him ‘X’. He lived in the Mossburn area and had a lengthy criminal record. The northern Southland rumour mill long held him responsible for Woodford’s disappearance and Sensing Murder reruns only stoked the gossip. Both of the psychics on the show mentioned him by name, but the words were bleeped for broadcast. “I’m friends with the ex-wife and the son of that person,” Bev Woodford says, “and when something like this happens they ring me, even though no one has mentioned names: ‘So and so’s been going on on social media about [X].’” Without fail, Bev says, the family members swear to her that X didn’t do it.

One tip came from someone with gang links in Southland, who said X accused him of owing money: “He made the comment to me that if I don’t pay that I will end up like Woody. Even today, and I don’t live in the south any more, I am still shit scared.” Another was from someone who attended a party X hosted: “It was late at night during one of these parties when a guy who I hadn't met before was there. He began to make jokes about ‘cracking a woody’. He was pretty well pissed and stoned. Every time he tried to carry on from this [X] would shut him up or threaten to shut him up permanently.”

X did not respond to a request to comment for this story. But he did speak to private investigators hired by Sensing Murder in 2009. Notes from the conversation are included in the police file: “There had been all sorts of theories about Allan’s disappearance,” X said. “Many are just not plausible. One is that he caught someone stealing and was dealt to by that person. I think the problem with that is that the town was small and if someone had done it the town would have heard.” He denied having anything to do with the disappearance.

Brian Hewett retired from the police in 2006, not long after he led the investigation that cracked another cold case — the 1987 murder of Arrowtown woman Maureen McKinnel. He doubts X was involved in Woodford’s disappearance. “He was a local troublemaker and he was a tough nut but I don’t see it.” Hewett once even asked X about it directly. “He said, ‘I was fair game. I was a name in the district. Anything that happened … they blamed me.’”

Mossburn’s main street, looking west. ‘X’ lived in the town at the time of Woodford’s disappearance, but has since moved to a different part of Southland.

Mossburn’s main street, looking west. ‘X’ lived in the town at the time of Woodford’s disappearance, but has since moved to a different part of Southland.

The police file has one final, tantalising lead, not linked to X. It is right at the back of the folder, and again came from the Sensing Murder investigators. They spoke to another man who went hunting around Waterloo a few weeks before Woodford disappeared. One afternoon the man and a friend were walking up a valley when, to their surprise, they came across Woodford and Orlowski.

“What caught both of our attention was a pack horse,” the hunter said. “It was loaded to the maximum with what I could best describe was a load about the size of an elephant saddle. It covered the horse’s back and was packed high… Whatever it was it had to be light as it was a huge load for a horse… If I had to guess what was under the cover I would say some sort of vegetation, either cannabis or ferns for the florists.

“I did not expect the reaction we got. Allan was aggravated and did all the talking. He just went off at us. He wanted to know ‘what the fucken hell are you doing here?’ I got the impression he did not want to see us.”

There is no other mention of stripping cannabis plots in the police file. Over the years, the notion has crept into versions of the homicide theory as a possible motive – some growers were getting back at Woody for raiding their stash by stealing his petrol and things got out of hand. But, like almost everything else about the disappearance, there is no hard evidence to support it.

Allan and Jean Woodford had been married for 45 years when Allan disappeared. SUPPLIED

Allan and Jean Woodford had been married for 45 years when Allan disappeared. SUPPLIED

In official circles, Allan Woodford’s disappearance defies categorisation. Along with the coroner’s “unknown” cause-of-death finding, the police register of missing persons, which includes “suspected suicide” among its classifications, lists Woodford’s case as “unexplained”. The equivocations are fitting. Brian Hewett concedes that, even by missing persons standards, Woodford’s case is strange. Almost nobody disappears leaving so little evidence to explain why. “It’s odd,” Hewett says. “It’s odd for a male to go missing in those circumstances.”

About three weeks after Woodford disappeared, his family resigned themselves to the fact he wasn’t coming home. But it took much longer to accept that they would likely never know what happened to him. “It probably took about 20 years for that to sink in,” Kerryn says. “[You] keep thinking one day, one day someone will come across something. A skeleton or a shallow grave. Or someone would come up with some information that they knew of somebody who had done something and point us to where a body could be located. [We] just hoped and hoped and hoped that one day we’d get a resolution.”

Woodford’s daughter, Kerryn McMaster, still doesn't know how or why her father disappeared 37 years ago.

Woodford’s daughter, Kerryn McMaster, still doesn't know how or why her father disappeared 37 years ago.

The case remains open. Southern district investigations manager Detective Inspector Shona Low said, “If there’s any further things for us to look at we will obviously look at that.”

Few of us care to admit that a loved one may be suicidal. We mistake our dread of such an eventuality for the unlikelihood of it happening. Allan Woodford’s family is an exception. They are prepared to accept this may be what happened. But at the same time, they are drawn to the homicide theory. Thirty-seven years after one of these realities likely claimed their husband, father and grandfather, the uncertainty of which one is worst of all.

“Not knowing is extremely difficult,” Kerryn says. “Not having him in our lives is the hardest part, but not knowing is the cruellest thing that you could possibly imagine. I don’t like the word closure because there’s never closure. You’ve just got to learn to live with the situation, but not knowing what you’ve got to learn to live with is difficult. I’ve lost a brother in a car accident, I’ve lost my sister to cancer and I've now lost my mother to old age. You don’t ever get over things like that. You just learn to live with them.

“But not knowing is really difficult because you can’t compartmentalise it in your life. Because there’s always that tiny little niggle… Did he do this to us deliberately or was he taken from us? And there’s no answer to those questions. So because there's no answer you’re always, always, always asking what the hell happened.

“Where is he?”

WOODFORD, Allan Gordon — In loving memory of our dear dad and grandad who left us ten years ago today.

The mountains hold him fast,

But we have him in our hearts.

Getting to the truth takes patience and perseverance. Our reporters will spend days combing through documents, weeks cultivating delicate sources, and months – if not years – fighting through the Official Information Act, courts and red tape to deliver their stories.

By supporting Stuff you'll help our journalists keep the pressure on. Make a contribution from as little as $1 today.