It’s been 26 years since lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender personnel were first welcomed to serve in the New Zealand Defence Force. But only in the past six years have any transgender personnel openly transitioned while serving. Kirsty Lawrence speaks to those on the front line of the force for change.

Trustworthy, accurate and reliable news stories are more important now than ever. Support our newsrooms by making a contribution.

Contribute Now

W hen Mark Mieremet answers the door of his Manawatū home, a warm smile crosses over his face.

For a moment you could almost confuse his Dutch accent with South African, a mistake you won’t make twice.

But what you can’t confuse is his gender.

Mieremet is a man. There isn't a single aspect of him that would suggest otherwise. The 45-year-old’s voice is deep, he looks masculine, he has facial hair.

But at birth, his assigned sex was female.

Mieremet was 11 when he says he realised he was born in the wrong body. He read an article about being transgender and it resonated strongly.

“I think I felt ashamed, or... how do you tell people this? So I never followed this up, but it was in the back of my mind.”

Growing up, his parents quickly stopped trying to dress him in girls’ clothing.

“It was a massive drama.”

A typical tomboy, it wasn’t until he hit puberty it became apparent how different he was.

“This is what boys do, this is what girls do, and I did the opposite.”

Even growing up, his siblings would say: “We have this sister, but she’s more like a brother.”

I n his early 30s, he left the Netherlands to backpack through New Zealand.

That quickly turned into living in New Zealand and, while he was looking into job options at a career expo, he came across the New Zealand Defence Force stand.

At the time he was told he had to live in the country for five years before he could join the military.

Mieremet always had military aspirations, with both his dad and grandad being officers in the army in the Netherlands. But, when he made the decision at 35 to transition from a woman to a man, he thought his military career was over before it had begun.

“It’s always been my dream to be in the military. [But] I reached a point where I just had to transition: this doesn’t make sense, this is not who I am.”

He wrote to his family back in the Netherlands to tell them his news.

“They took that really well.”

Making the decision to transition wasn’t scary, but a relief, he says.

“It was really hard trying to be a girl when I’m not.”

He had mastectomy surgery to remove his breast tissue and create a more masculine chest, which is the most significant medical intervention he will do at present.

Given the lack of funding and the waitlist for public surgeries, most surgeries for transgender people come out of a person’s own pocket and at large cost.

For Mieremet, transitioning was the easy part.

When his transition was complete, Mieremet thought about joining the military again, so he put in a request to see if the New Zealand Defence Force would accept him.

To his surprise, he was told it was fine to join as a transgender person, he just had to wait until he had lived in New Zealand for the full five years.

This dream became a reality in 2014 when he joined the air force as a medic.

But being the first, and still the only, person to have transitioned before joining came with its own hurdles and for the first few years nobody knew.

“You don’t transition to tell everyone you transitioned, you want to be yourself.

“I just wanted to be one of the guys.”

Basic training had its own challenges, as recruits live in shared dorms and have shared living spaces, including bathrooms.

“You get quite creative.”

Going to the toilet when he was in the field with the guys was another challenge as if others came to join him, he would worry.

“I would think, ‘S…’ And if people didn’t know, it would be stressful.

“I can’t just go pee against a tree.”

But as time has passed he’s become more comfortable.

“Now I can proudly wear the uniform that fits me and do the job I love doing.

“I am way more confident in my own skin.”

C urrently based at Ōhakea, he joined the air force as a medic and trained in Burnham.

He has now moved into psychology, with only two exams to go until he can get his registration and work as a fully qualified air force psychologist.

Each day at work is different for Mieremet , who does everything from selection assessment, which is making sure people are fit for the roles they’re applying for, to mental health skills or resilience training.

He’s passionate about his job and his dedication to work is a driving force, because as well as wanting to keep his past private, he also didn’t want people to think he was using it as an excuse.

“I’ve always worked really, really hard. I feel super privileged I can be in the Defence Force.”

Mieremet says he is more open now as he feels it’s important to get education out about the topic.

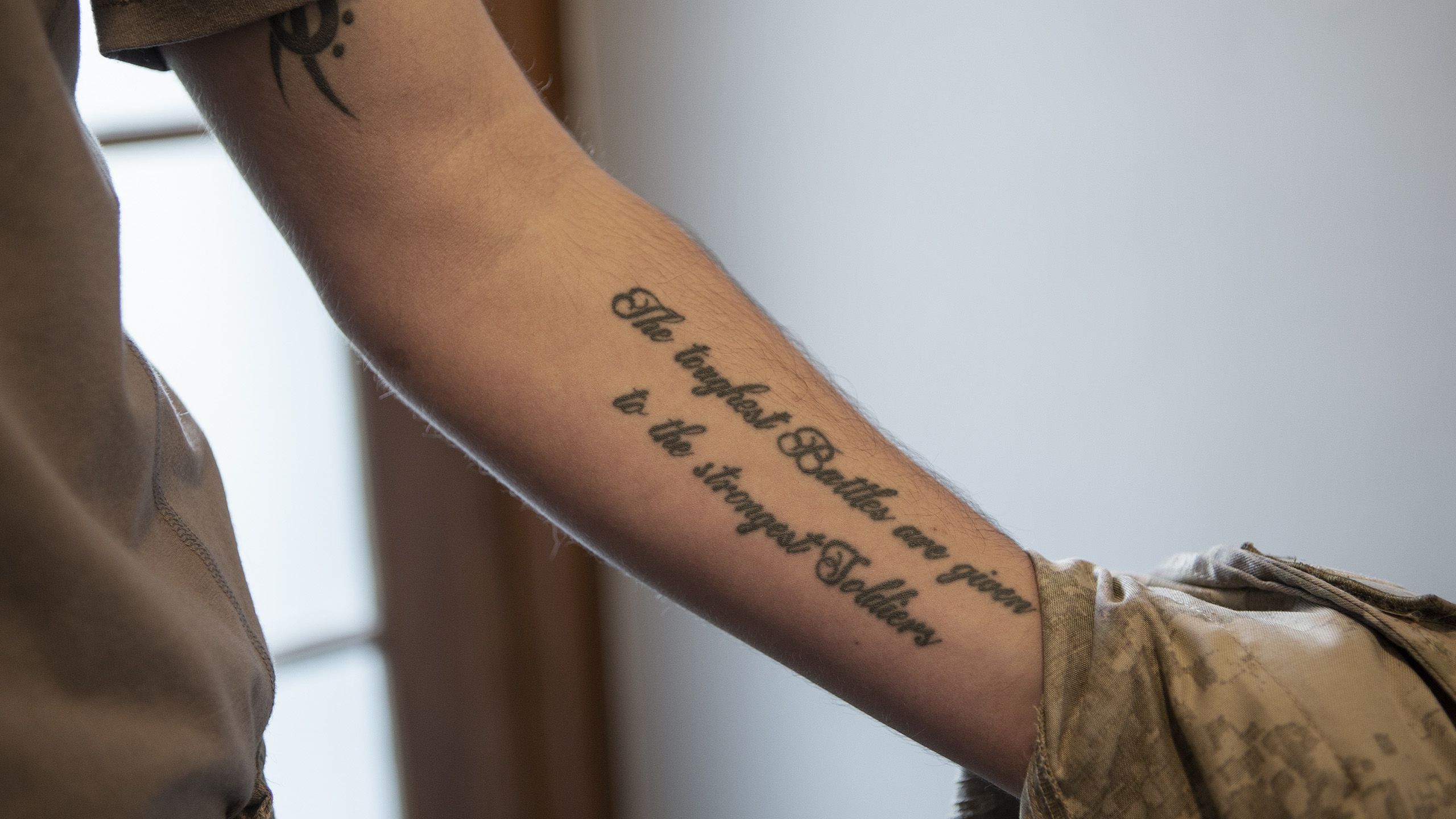

In 2019, he took part in a Defence Force Photography Exhibition to celebrate 25 years of the organisation being LGBTQI inclusive, and said a lot of people were surprised to learn about his past.

“People were like, ‘Wow, I would never have known that.’”

Mieremet is passionate about challenging stereotypes about what they think transgender people should “look like”.

“They see things on TV and have an idea. Then, when you tell them, they are like, ‘Oh, wait a minute, you are just as much a guy as we are.’

“It’s definitely opened the eyes of people.”

He wants to let other transgender people know that a military career is an option for them, if they want it.

“You can join the Defence Force if you can do the job – they pick you for your talent and ability.

“For a lot of people concerned about a career… if they know you can still join [the military] or do whatever you want to do with your life, that’s really important.”

That’s what he missed growing up, he says, and that’s what he is hoping to show others now.

“I didn’t have those positive role models. I didn’t have someone to look up to… and that would have really helped me.”

When Hemi Frires decided to tell people in the Defence Force he was gay, he was terrified.

Ten years ago, being openly gay wasn’t even talked about and the system back then was a “one size fits all” model.

When Frires came out, he did some research into support the Defence Force could offer the LGBTQI community

This saw the formation of OverWatch, a group which provides support and guidance to NZDF’s Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Questioning (GLBTIQ) community – as well as to their commanders and managers, families, friends and colleagues.

As the current chairperson of OverWatch, he has a vested interest in making sure the Defence Force is inclusive.

“New Zealand society has shifted in the last 10 years. These days we are finding a lot more people coming already out and open and comfortable with that.

“They almost come with this mindset, ‘This is what I am, what are you going to do? I’ll kick the closet door down.’ And everyone goes, ‘Cool, crack on.’

“But back in the day when you didn’t talk about those things, it was a terrifying thing to do.”

Frires felt people knew they could be involved in the Defence Force no matter what their sexual orientation was, but in the past six months he says they have been approached by half a dozen people asking the question: “I’m trans, can I join the military?”

They mainly want to know if being transgender will be a problem, as well as looking for guidance on how it will work.

“People [don’t] think it’s not an issue, but they don’t see it as out of reach either.

“Which I guess is a step above ‘it won’t work for me, I won’t even try’.

“But it’s not yet the open understanding that… there is a place.”

This open understanding is something Frires wants to work on and he sees transgender issues as the next major social justice cause for defence.

“We are in pretty good shape and it’s not an easy issue to untangle. So I see this as a big place we need to work on.

“Not to diminish the other things still ongoing. We are still working on a lot of stuff around the organisation and New Zealand society.”

While the Defence Force is open to having transgender personnel, there are complicating factors which have to be considered.

“We do find they can be caught up in the medical process.

“We have high standards in medical and recruitment, so there are some fairly disqualifying factors in there.”

One such factor in the application process is that people on permanent medication can not be accepted into the Defence Force, which means quite often transgender people are ruled out from the outset.

The medication rules are designed to make sure people have access to medication they need while away on deployment, which might not always be possible.

But, it depends on individual circumstances. As Frires points out, it would be fine for someone who wanted to join the army band to be on permanent medication.

“They are not a unit to deploy into Iraq. But the special forces would be a little bit more complicated.”

In the current Defence Force application process there was no way to differentiate between these roles when applying.

However, Frires says because the New Zealand Defence Force is small enough, if someone appeals the policy decision, they can be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

When the first transgender person approached OverWatch in 2014/15, Frires says it highlighted a black hole in policy they needed to work on.

So they started to formulate guidelines about supporting someone transitioning in the workplace.

Having someone in the air force who had gone through this process meant they had already learnt a lot, Frires says.

He has since left, but there had been several transgender personnel since who have come out as transgender.

Besides issues around long-term medication use, another area that needs further consideration is deployment.

Some deployments would just not work for transgender, gay or lesbian personnel due to legal and cultural differences, as well as medical attention that could be needed.

Basic training also comes with its own complexities since recruits are forfeiting their personal autonomy and living in communal areas.

But the Defence Force is committed to making sure it’s inclusive, with New Zealand currently ranked the number one military in the world for inclusion.

While people in the military might have positive experiences, University of Waikato senior lecturer Jaimie Veale says a recent report showed that people’s experience of being transgender or non-binary in the wider workplace was mixed.

Of the 1178 people surveyed in Veale’s Counting Ourselves report, 71 per cent said their colleagues were mostly supportive of them, with 15 per cent saying some were supportive and 6 per cent saying they were unsupportive.

More than half of those who responded had not told anybody at their work because they feared discrimination.

Out of those whose transgender or non-binary status was known at work, 26 per cent had experienced colleagues disclosing information they shouldn’t have to others, while 21 per cent stayed in a job because they were they worried they wouldn’t be employed by another company.

Veale said she thought attitudes in New Zealand towards transgender people were changing and becoming more accepting, but there was still issues, especially with discrimination.

Almost half of those surveyed – 44 per cent – said they had experienced discrimination in the past 12 months.

“There are definitely still issues there.”

E nergy bounces down the phone as Sawyer Coote cheerfully says that not a lot offends him, so ask any questions that spring to mind.

“You don’t know what you don’t know, so I’m not going to crucify you for it.”

This relaxed attitude seems a common theme in the 30-year-old’s life, who describes his journey to becoming Sawyer as very different to other transgender people.

“I’m relatively late to the party.”

It was only three years ago, at the age of 27, that Coote decided it was time to be true to who he really was.

“It’s been an ongoing journey since then.”

He says he didn’t hate being a woman. But, when he started to think about having a family of his own, he realised something was off.

“I was thinking about what that might look like for me and I thought, ‘Have a wife and be a husband and dad.’”

An openly gay woman before transitioning, Coote thinks he figured out he was transgender later than everyone else because he thought everyone felt the same way as him.

“When puberty happened, I thought everyone hated it.

“That’s why I figured it out so late.”

Growing up in Invercargill as Sarah, the thought of being transgender never crossed his mind.

“I didn’t realise that was a thing.”

Big conversations in his family always happened at the end of his mum’s bed, so it was in that spot he finally decided to share the news he was transitioning.

“I said, ‘I really need to talk to you,’ and I started crying.

“I didn’t care about anything else, because Mum was in my corner.”

Coote joined the military at 24 and says the first step after realising he was transgender was to vist the GP on base.

“I cried, which is weird, because I am not a crier.”

She told him it was great and was supportive, but didn’t know how to help him further at that point. Instead she approached her contacts outside the military for answers.

Coote was sent for a psychology assessment, then back to his GP for a referral to an endocrinologist – a doctor that specialises in hormone replacement therapy.

“I felt like there was nothing I couldn’t have gone to [my GP] with.”

A lance corporal in the army, Coote’s initial thoughts were around how he was going to tell his colleagues.

“I was worried about how everyone would take it.

“Am I going to keep my job? Will they still want me? Am I going to be an admin nightmare?

“I used that nerve to drive me to stay employable.”

He was given two and a half weeks’ sick leave to prepare to make the announcement, which he says he is grateful for.

“It gave me the opportunity to get sorted… I got to see my psych[ologist] and go to appointments without having to explain to anyone before I was ready where I was going.

“When I came back to work, I asked to see my big boss.”

He told him he wanted to tell his colleagues why he’d been off sick.

“I said, ‘This is who I am, this is my journey. I’m telling you because I trust you, but you have a right to know and I intend to be out and proud at some point.’

“He said, ‘That’s really cool. Look I don’t know much about it but I’m on board and we will figure it out.’”

Coote decided to tell the rest of his team on the Thursday before an Easter weekend, so when he came back to work on the Tuesday, he would change from Sarah to Sawyer. A lot of transgender people don’t share their previous name as they see it as a “dead” name, but Coote says he was Sarah for 27 years and she helped shape him into the person he is today.

He wrote a letter that his boss read out for him. There was nothing but support from his colleagues.

“I expected everyone to make mistakes. For a wee while there would be wrong pronouns, but as long as everyone tried, I wasn’t upset and everyone was really cool.”

If there was any negativity towards him, he says he was never exposed to it.

“I had some pretty awesome mates and co-workers and colleagues who would have stamped anything out.

“If it did [happen], it never got to my ears.”

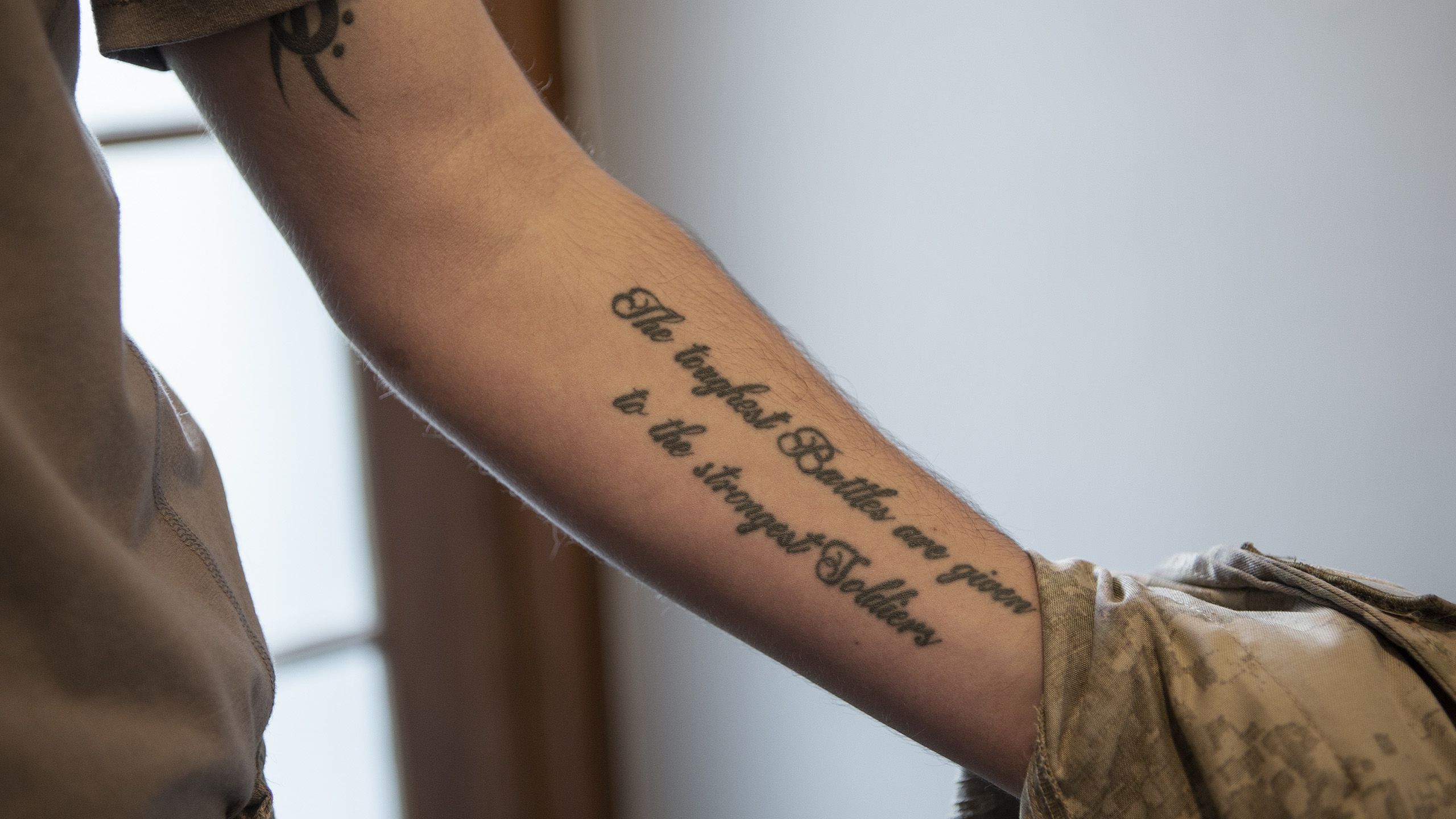

After Coote saw his endocrinologist he started taking testosterone supplements, which essentially stimulate a second puberty.

“It’s helped me grow facial hair and deepen my voice. I’m a lot stronger [now].

“It’s been really, really positive for me and it’s something I will continue to take for the rest of my life.”

He also had mastectomy surgery.

“For me, I wanted some medical intervention to reflect who I am on the outside.

“That’s the biggest medical intervention I will do at this point.”

His chest surgery cost $20,000, and friends and family donated money so he could get it done.

While it might seem like a little change to most people, the surgery makes a big difference to Coote. He can now take his shirt off when he is at the beach, and do all the things other men can do.

“It felt so life changing, but still so normal too.”

Coote doesn’t understand people who have strong opinions on the topic, as to him it’s his life and it shouldn’t affect anyone other than himself, his partner and his direct family.

“It’s like, it doesn’t hurt you mate, I don’t know why you’re losing sleep over it.

“You need to get better work stories or some hobbies if it’s cutting you up”

He has encountered two sets of supportive colleagues, as he changed his trade around the same time he started transitioning.

I nitially a medic, he now works as a logistics supply technician at Burnham in Christchurch. Day-to-day, this sees him liaise with different units within the army to order gear and supplies, as well as do physical inventory.

While some militaries around the world won’t accept transgender personnel, Coote says the fact that New Zealand’s Defence Force does was great, and showed that if you want to be in the military it doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from.

While the military is one area of his life he has navigated, dating is another.

Coote is engaged to a woman, Penelope Hawker. The pair met on Tinder and are getting married in January.

Coote says their relationship is just about two people being who they are.

“It’s got nothing to do with a gender or the physical. We are loving someone for what they are, and that’s all anyone wants really.”

They had mutual friends, so Hawker already knew about his history, but they still had a conversation around it.

“I identify as a straight male and she sees me as that.”

Hawker said that even if Coote had stood in front of her fully naked prior to his surgery, nothing and nobody could have convinced her he was a female.

“He has such a masculine energy about him,” she said.

Prior to Coote, she only dated men, but considers herself bisexual.

The pair are open about their relationship, and Coote says there is only an elephant in the room if you don’t address it.

“Because of that we don’t get asked a lot of questions.”

Being a woman and trying to get a building apprenticeship in 2008 was difficult for Tony Eaglestone.

At the time, the army was one of the only places he could get an apprenticeship. However, getting his fitness to a point where he could pass the testing was difficult.

But he worked hard and, at 29, he joined the Defence Force as an openly gay woman, despite already knowing he was really transgender.

But after working so hard to be accepted into the military, the now 38-year-old decided to put those feelings to one side.

Not someone to dwell on what he can’t control, he instead focused on his military career.

Plus, joining the military as a woman had some upsides in basic training, he said, with fewer people sharing dorms and showers than the men. So he decided to concentrate on the positives.

Back then, he thought he’d have to leave the military when he wanted to transition.

But in 2013, after an accident with a bench damaged his hand, he had to take time off to rehabilitate his injury.

He had a lot of personal drive to tick all the boxes to get back to work.

“Then I thought, ‘What else can I do with this drive?’

“I wanted to transition and start this process and, if it works it works and if it doesn’t… I got to the point where the transition was more important than the consequences.”

At this point, in 2015, there was only one other transgender person who had transitioned while in the defence force, a woman in the air force.

Knowing someone else had already been through the process and was accepted, made the decision easier.

He said he “probably” was nervous, but by then his mind was made up.

Eaglestone went to his GP on base at Linton Military Camp, but they didn’t know much more than he did.

“It was a case of everyone working together to work out what needed to be done.”

At that time, in Manawatū, he had to go through three months of counselling to get a piece of paper saying he was mentally competent and could start hormone therapy.

“At the end of our first session [my counsellor] said, ‘Yeah you are sweet, but we have to do three months, so is there anything else you want to talk about?’”

When he transitioned, there was only one endocrinologist working in Manawatū, and treating hormone problems wasn’t classed as essential, so no transgender patients were being seen.

“If I had been 20 and on my own that would have been devastating, but the medical support you get in the Defence Force I wouldn’t get any other place,” he says.

Eaglestone’s GP spent time on the phone calling around to find out where he could see someone and where he needed to go, which was Wellington.

This was another positive to being in the Defence Force, says Eaglestone: medical appointments are considered meetings and you have to make them.

When he started to talk to people about transitioning, he discovered a military friend in Auckland was also transgender, but she had left because she didn’t feel like she could transition in the military.

When he decided it was time to tell the people he worked with, a Massey University psychologist came to base to tell them the news and answer any questions people might have.

“I started taking hormones from there. It’s not something you can hide.”

However, telling his peers was fine, he says.

“The place I expected the most problem was the place I had the least. I have never had anyone misgender me at work.

“Everyone has been interested and supportive. I can genuinely say I have been incredibly lucky.”

He has had chest surgery and, at this point, has no plans for further surgeries.

“To get bottom surgery it’s close to six figures.”

He hopes that knowing others have transitioned, and been supported by the Defence Force, will make it easier for others in the future.

“People have served with a transgender, so they know it’s not a big deal.”

After 29 years living as a different person, Corporal Marcia Cooper isn’t too worried about the Covid-19 lockdown interrupting some of her transition timeline.

Cooper started her transition from a man to a woman in July, 2019 after 11 years in the air force.

Prior to lockdown she was starting to get her legal paperwork sorted, getting fitted for a female air force uniform and preparing to tell her work colleagues.

But while some of these things were delayed, like most things to do with her transition, Cooper is just excited for the day it finally happens.

To get to where she is today, Cooper says she first had to realise it wasn’t normal to wish you were the opposite gender.

Then it got to a point where she not only wanted to change it, but needed to change it.

Now 30, Cooper says the main thing that had her thinking about her gender was her love of computer games. Whenever she had to design a character, she was always drawn to the women.

After talking to her psychologist, who she was already seeing as she suffered from depression, the pieces fell into place and she started to transition.

One of the first things Cooper did was approach OverWatch.

“It did make me nervous.”

But once she had, she found out she was not the first transgender person in the air force and there were already guidelines in place.

After making the decision to transition, she told her commander.

“I said, ‘This is what’s happening, this is what I plan to do, is there any issue?’

“I got nothing but support.”

Cooper initially wanted to speak to Stuff anonymously as she had not told her wider workplace, but decided instead this was a good opportunity to share her news.

“The initial plan was to stand up and give a presentation in person… do it all in one day and then take time off to let my hair grow out and give people time.”

However, Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdown changed that plan – instead she told her workmates via Zoom.

Working as a Communication and Information Systems Technician, she deals with everything communications or IT systems related.

At present this means working on a project around how the Defence Force carries out its communications and the different IT systems used.

Her role sees her working a variety of hours and days, but it’s what she has done ever since she joined the air force.

Cooper was sized up for a female uniform in January, so she left the air force pre-lockdown in a male uniform and returned with a female one, which she has worn once on base for a squadron medal ceremony.

As she is still going through the process, Cooper says it’s been interesting getting all the legal documents sorted, with most responses being positive.

Getting her driver’s licence was a little complicated. While staff were positive towards her, there was confusion around how to do the paperwork.

“It was them trying to figure it out, so a bit of an admin burden.”

Since starting her hormone replacement therapy, she has noticed her overall strength dropping.

The hormone therapy has also helped with fat redistribution, with fat heading to her belly, hips and thighs.

Even though she is changing physically, she says she still has a lot of the same hobbies and likes all the same things.

“I’m still a Star Wars fan and they still call me Coops.”

Because lockdown happened at a time Cooper was starting to become herself, she says there are still a few things to get sorted, like a new wardrobe, but she is excited.

“That’s going to be a lot of fun.

“I’m definitely excited to try new things and see what works. I get to be me, but I’m nervous because it’s not something I have done before.”

She likes to think the people she initially joined the air force with would have accepted her if she shared the news back then, but it was more the commanding officer and greater air force perspectives she was worried about.

“With society in general, 20-30 years ago, it was almost unheard of.

However, she admits the changes are what has helped her feel comfortable.

“If I had realised early in my career, maybe I would not have stayed in.

“In terms of general respect, as society moves on we need to make sure the Defence Force follows, and there is not a disconnect.”

As she is new on her journey, she has been looking at options available to her and says with New Zealand’s funding for surgery it was tough to get accepted for public funding, so private was the most obvious option.

She says she will probably go for the full gender reassignment surgery, but that will be a waiting game.

“New Zealand doesn’t have anyone to provide [gender reassignment surgery] at this stage.

“There is a surgeon who can do it, but they are currently not offering it.”

Her other options are to save up enough to get the surgery done in Australia, especially if New Zealand borders open there first, rather than Thailand.

“It took me 30-odd years to realise, what’s waiting a couple more years?”

Words: Kirsty Lawrence

Videos and Photos: David Unwin, Joe Johnson and Lawrence Smith

Design: Kathryn George

Editor: Nicola Brennan-Tupara and Wayne Timmo

Become a Stuff supporter today for as little as $1 to help our local news teams bring you reliable, independent news you can trust.

Contribute Now