Trustworthy, accurate and reliable news stories are more important now than ever. Support our newsrooms by making a contribution.

Contribute Now

High performance athletes are renowned for being fastidious planners.

For Olympians, the first eight months of 2020 would have been more regimented than most. The period would have been broken down into one-week blocks, outlining training camps, key build-up events, targets they’d need to be hitting in training and performance goals.

There was no room built into their wall planner for disruptions.

The end goal was to be firing for a two and a half week period over July - August.

This period - just over two months out from the start of the Tokyo Olympics - would have been crunch time for them all.

In a sliding doors world, Black Sticks star Gemma McCaw would have already toured Australia and Europe this year, before going into a gut-busting heat camp. Around about now, she and the rest of the squad would be nervously waiting to hear if they’d made the final cut for Tokyo. Those selected would then be preparing for the last big push heading into the Games.

“Now we’re in a position where we’re just waiting to hear what happens next. We have to take it as it comes, which is quite an unfamiliar position to be in.”

McCaw is among hundreds of Olympians and Olympic hopefuls now confined to a roller doors world - training in garages around the country, doing their best to maintain a performance edge.

As we approach the end of the lockdown period, Stuff caught up with eight athletes about their experiences training in isolation. Each spoke candidly about the mental, physical and emotional challenges they’ve faced over the past six weeks.

Their unique training settings have been captured by photographers from Getty Images.

/**span.lightHighlight**/For the past six months, Gemma McCaw’s life, and that of her family’s, has been all about two weeks on the calendar in July-August. The Olympic Games./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/When she first made the return to hockey four months after the birth of her first child, Tokyo wasn’t even on her mind. She was just doing it to get fit and feel part of a team again. She was doing it for her./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/But then the competitive instincts kicked back in. The Black Sticks’ selectors were asking about her availability and she thought “maybe I can do this”. And she could. By November last year, McCaw was in camp with the Black Sticks./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Since the team re-assembled on January 5, her family has moved back and forth between their home in Christchurch and Auckland. Her husband, Richie, put his projects on hold, while mother Michelle took the year off teaching to help out./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“There’s just so much that goes into it. I just look at my family and how much they have allowed me to do this, I’ll be forever grateful. We had that July-August date in mind, we knew we could keep going until then,” she says./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Then it all changed./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“The Olympic Games being pushed back a whole year really throws a spanner into the works. We went from being absolutely full-on, to nothing. I probably took a week or two to come to terms with the new situation. It’s been a period of readjustment and reflection.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Early on, McCaw says she didn't put too much pressure on herself to follow her programme “to an absolute t”. Both she and Richie are exercise fanatics, so staying fit hasn’t been a problem. But again her competitive instincts soon kicked in. She’s back doing sprint sessions, has rediscovered watt bike hell, and is doing the odd bit of skill work in her backyard./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/But it’s the other challenges she is appreciating more - like learning to cook new dishes, and how to sew. Both her mother and grandmother were seamstresses. Now her mum is teaching her to make clothes for daughter Charlotte./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/She’s also been reading a lot. She made the rule that in those quiet moments rather than mindlessly scrolling through her phone, she’ll instead pick up a book. She’s mostly stuck to the rule./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I’m going through a couple of books a week. I love that you learn about new people, or a new country or a different period of time.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Somewhere in amongst it all, McCaw has learned to let go of the calendar./*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/Photos: Kai Schwoerer/Getty Images/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Down a quiet cul-de-sac in the rural Waikato town of Te Kauwhata, weightlifter David Liti has begun attracting an audience./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Training in the garage isn’t really an option for Liti. At six-foot tall, he doesn’t even have to stretch to touch the ceiling. His coach, Tina Ball, who Liti lives with, is worried too that the powerful lifter will break the floor of her garage with the weights he can throw around./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/So, each day (weather permitting) the Commonwealth Games gold medallist sets up his mats at the end of the driveway - the only flat slab of concrete available to him - and gets to work./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/It’s become a bit of a spectacle for the local residents./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“The first day we set up outside some of the kids from down the road came down and they were sitting on their bikes just watching for like 30 minutes. Now we’re four weeks into lockdown, a lot of people walking past will stop and watch. It’s pretty funny.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Liti uses the audience as motivation for his training. Without his peers to train with as motivation, he figures this is the next best thing./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/The 165kg powerhouse, known to his coach as ‘Big Bear’, usually commutes the 70km from Te Kauwhata to Ball’s Ellersie gym each day for training. He doesn’t miss the driving, but he does miss seeing his family in Auckland./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I’m the second youngest of 11 kids, so there’s a lot of us. I usually try to see my family every week when I’m in the country so that part has been hard./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“But I’m just one of five million people. I can’t complain. Everyone is doing it tough.”/*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/Photos: Phil Walter/Getty Images/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/There are days when the numbers on the screen taunt Lucy Spoors./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Spoors, a member of the world champion women’s eight rowing crew, has been consigned to the ergometer in the garage for the past month./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/She misses being out on the water. She misses the therapeutic sound of the oars slicing through the water, and the gliding sensation that comes only when all eight rowers are working in perfect synchronicity./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/In the garage of her Cambridge flat there’s nothing but the whirring of the machine, and a small screen staring her in the face./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“The erg can be mentally challenging, because you’re always seeing your own numbers,” says Spoors./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“You’re consistently getting instant feedback on what you’re producing, so it can feel a little bit confronting especially if you’re having a bad day.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/It helps that she shares her flat with three other members of Rowing NZ’s elite team - her boyfriend Brook Robertson, a member of the men’s eight, sister Phoebe, a reserve for the women’s sweep boats, and Olivia Loe, one half of the world champion women’s double. They are all in the same boat, figuratively at least./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Prior to lockdown, the New Zealand rowing team were in an intense period of training in preparation for the European season. Now confined to dry land, the training remains just as demanding with the flat logging some big kilometres on the erg./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“Our days have been exactly as they would be at Karapiro. We’re still doing fulltime training, so we’re training twice a day, and sometimes three times a day when we have a weights session.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I don’t think any of us have ever spent this much time on an erg in our lives.”/*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/Photos: Michael Bradley/Getty Images/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/In a quiet subdivision in Karaka, Olympic trampolinist Dylan Schmidt soars high above the rooflines./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/His body shaped like a projectile, he launches himself skyward, twisting and turning in the air with rigid precision. In the next sequence he opens his arms out. For a moment, he hangs in place like he is suspended in the air./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/In a sense the lockdown has taken Schmidt back to where it all began: the trampoline in the backyard./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/His childhood trampoline still sits at his parents’ home in Karaka, a once-rural pocket of south Auckland, which has become Schmidt’s training base for the past month. This trampoline isn’t like the ones you’d find in regular suburban homes. His parents bought the specialised equipment when Schmidt and his older siblings, Callum and Rachel, were beginning to show promise in the sport./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Schmidt was just six when the tramp showed up at his Waihi home. Back then the Schmidt family travelled to Auckland three times a week for training, spending the other days training at home following a plan developed by their coach. Much like what he is doing now./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/A competition routine for Schmidt only lasts about 20 seconds. Athletes must link together 10 elements, and are judged on height, technique, execution, continuous rhythm, and body control, as well as the degree of difficulty of the skills./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/It takes an extraordinary amount of work to produce 20 seconds of perfection./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Schmidt, who was one of the surprise packages of the Rio Olympics with his seventh place finish, usually spends six days a week at his training centre in Mangere, in addition to three weights sessions a week./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/He estimates at home he can only do about 15 per cent of what he can do on a proper Olympic tramp, so for now, he’s focusing on basic skills and technique. And appreciating the view./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“It is kind of cool jumping up and seeing the whole neighbourhood. It’s quite freeing in a way,” says Schmidt./*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/PHOTOS: HANNAH PETERS/GETTY IMAGES/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/To many, 2020 will be remembered as the lost year of sport. Not for Tori Peeters./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/This has been Peeters’ breakthrough year. In the space of three months over the New Zealand and Australian athletics season, Peeters rocketed her way up the women’s javelin rankings, establishing herself as a genuine world class competitor./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Going into the season, Peeters had a career best throw of 57m. She finished the summer with a personal best of 62.04m, putting her right in the frame for Olympic selection./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/The sporting shutdown may have cut off her competitive opportunities, but Peeters is determined it won’t halt her momentum in the sport./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I was quite gutted about not being able to continue that form into more competitions that were only going to become bigger and more important, but I firmly believe I can find that rhythm and performance state again,” she says./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“When I was throwing well during the season there and throwing my 62m, I made a real effort to try and remember what it felt like, what it looked like, what it sounded like, so I can call upon those things again to get me back in the performance state to throw far.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Peeters hasn’t really done any throwing in lockdown. Instead she’s used the time at her boyfriend Cameron Moorby’s parents farm just out of Te Awamutu to focus on strength and fitness. She’s commandeered one of the garages on the property and turned it into her gym. Being put to work on the Moorby farm - something she’s used to, having grown up on a dairy farm in Southland - has also helped with her fitness./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“My coach [Debbie Strange] and I thought this would be a good opportunity to have a wee breather from it, but once a week just go out and roll my arm over with a light ball, or do some standing throws with a javelin,” she says./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I’m definitely missing it now, and I can’t wait to get back on the track and throw the jav around.”/*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/Photos: Michael Bradley/Getty Images/*/*

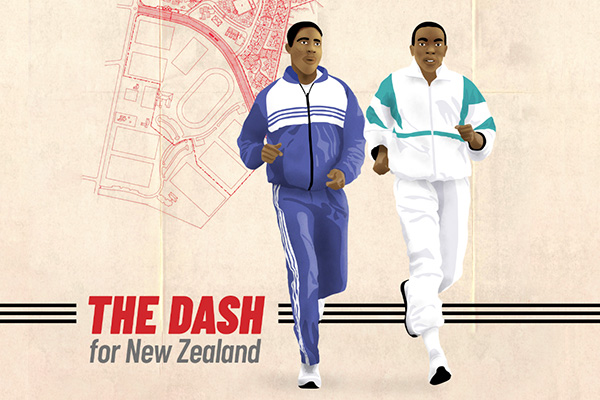

/**span.lightHighlight**/It took David Nyika 10 years to achieve his dream of qualifying for an Olympic Games. For him, setbacks are nothing new./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Nyika, who won back-to-back boxing golds at the 2014 and 2018 Commonwealth Games, secured qualification for the Tokyo Games in March following a hectic campaign that saw the New Zealand team forced to travel across Asia, Europe and the Middle East due to the impacts of coronavirus./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Having narrowly missed out on a spot at the Rio Olympics following a series of controversial decisions in the regional qualifying tournaments, the postponement of the Tokyo Games to 2021 is another frustrating hold-up./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I’ve been working so hard for 10 years and for me to finally get my break and then for it to be pushed back is a little bit frustrating but at the same time, I have accomplished the goal now, that doesn’t change, now I have a year to make sure I perform at the Olympics,” he says./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“For me, I can just focus on the next year or so of preparation.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/The chaotic qualifying campaign took it out of Nyika both physically and mentally. Lockdown life has forced the 24-year-old to slow down./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/He says he’s been enjoying the simplicity of his new training routine./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Each day, Nyika and his dog George, an English springer spaniel, walks down the road to his old high school, Hamilton Boys, with a boxing bag over his shoulder. He’s found a sturdy tree inside the grounds of the school that he can set up his bag and get to work./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I’ve actually been really enjoying the change of pace,” says Nyika./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I think it is just the quality of time. We’ve been able to slow things right down as opposed to stressing about daily life.”/*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/Photos: Michael Bradley/Getty Images/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Angela Petty has found lockdown a constant mental battle./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/First, the middle distance runner had to get her head around the postponement of the Olympic Games, which threw four years of careful planning out the window. Then, it was the uncertainty over when she will race again. Now there’s the nagging doubts as to whether the Olympic Games will even go ahead next year at all./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/It’s not just her sporting goals that have been weighing on her mind. Petty and husband Sam, who is also her coach, have other plans to consider./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I must say it has been pretty hard. The big one for me was we were looking at starting a family soon. If the Olympics were this year we were thinking of starting trying at the end of the year, so now it is pushing all that out as well,” the 28-year-old says./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“So that’s the hard thing for me, I do want to be a mum and I don’t want to keep pushing it back another year, and another year, and another year.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/The start of lockdown coincided with a two-week end of season rest for Petty. When those two weeks were up, finding the motivation to get back into running again was difficult. With no event on the calendar to aim towards, she was torn between the idea of taking an extended break, or getting a headstart on building a strong base for next season./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/It took one run around the park close to her Christchurch home to find clarity again./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“The part of me that just loves it anyway kind of kicked in again, and it was good to get back to it, just getting outside and being in the fresh air,” she says./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“I am trying not to focus on all the uncertainty and just enjoy training and do it because I love it anyway.”/*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/Photos: Kai Schwoerer/Getty Images/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Annalie Longo loves being in a team environment./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Being surrounded by your mates all working hard towards a common goal is part of the appeal of football for her./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/So too is match day. Nothing beats the adrenalin you get when you’re in the heat of a tough game, says Longo./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“One of the reasons I chose football was because it is a team sport and you get to go to training and hang out with your mates every day, so it has been an unusual challenge, it is almost like going back to being in an individual sport,” Longo says of the past month./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“Definitely, I miss the competitiveness and being able to play. We train the many hours that we do to be able to play the game, so it’s a struggle when you do all this work and you don’t get the good part, which is getting out on the field with your mates./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“That mindset is a bit of a challenge.”/*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/Longo’s season went from 100 to zero in the space of a day. At the beginning of March she was travelling to Portugal with the Football Ferns for the Algarve Cup. After losing to Norway in the third place play-off, Longo flew to Melbourne to link back up with her Melbourne Victory side on the eve of their W-League semifinal against Sydney FC./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/The Victory were not victorious. The following day Longo returned home to Christchurch, where she lives with partner Nikki and her two children, for a stint of two weeks of self-isolation, which ended right about the time the country was going into level four lockdown./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/As Mainland Football’s women’s development officer, Longo has had to juggle her responsibilities as both player and coach from home./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/She’s got a rebound net in the backyard for skillwork, while the trampoline is useful for stability exercises, and the garage - already set up as a dance studio - now accommodates a fair bit of gym equipment as well./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/She also runs online coaching sessions for young up and coming players in the region./*/*

/**span.lightHighlight**/“It’s about keeping their skills up, but also to keep them engaged and connected. I think it helps me as much as it does them.”/*/*

/**span.darkHighlight**/Photos: Kai Schwoerer/Getty Images/*/*

Become a Stuff supporter today for as little as $1 to help our local news teams bring you reliable, independent news you can trust.

Contribute Now

Words: Dana Johannsen

Visuals: Getty Images

Design: Aaron Wood

Editor: John Hartevelt