At its best, it’s the skill to burst the best defence in an instant. A game-turner. A World Cup winner. Tony Smith explains the art of the offload.

It’s the 2015 Rugby World Cup final, and the All Blacks have just gone ahead 16-3, moments before halftime. Conrad Smith - playing his final test - had made a slashing break to set up Nehe Milner-Skudder for the All Blacks' first try.

Strange then, for Smith to be replaced.

It was a calculated risk, yanking the world's best centre for Sonny Bill Williams, a man who had played just four minutes in the 2011 World Cup final.

Williams was charged with adding a different dimension to the All Blacks' attack.

Stakes were high. The Wallabies needed to score first in the second half to stay in the hunt. The All Blacks needed a try to cement an ironclad grip on the Webb Ellis Cup.

New Zealand’s coaches soon struck paydirt.

In just his second minute on the pitch, Williams hurtled on to a Carter pass, crashed into Wallabies flanker Michael Hooper and flyhalf Bernard Foley, spotted Milner-Skudder to his right and flicked the ball out the back of his hand. Only a desperation tackle from behind by Tevita Kuridrani, aided by Sekope Kepu, stopped Milner-Skudder scampering all the way.

One phase later, Williams swerved past Hooper's flailing arms, committing halfback Will Genia and prop Scott Sio to the tackle. He spun and turned his back on the would-be Wallabies tacklers, flicking the ball to Ma'a Nonu.

Nonu ducked through a hole left by Hooper and stepped a couple of defenders on a mazy run to the try-line. At 23-3, the World Cup final was all but over. Two deft deliveries in the space of eight seconds pushed Williams to the top of the most offloads category at the tournament, with 13.

In rugby, the offload is the most beautiful form of attack; it’s sleight of hand that puts runners rampaging into open space, as defenders grasp at thin air, or are absorbed tackling a player who no longer has the ball.

It’s a rhapsody, a comedy, a symphony and a play, as Rod Stewart might put it. And All Black Sonny Bill Williams is the composer, the conductor and the leading man. He’s an Offload Meister, with an array of defence defying weapons - the backhander, the stretch and slip, the pop pass. All are things of beauty, refined over nearly two decades at the top of rugby and rugby league.

Williams didn't invent the offload, but he and league players such Sam Burgess and Israel Folau have turned it into a much-aped art-form. All Black midfielder Anton Lienert-Brown has learned the art as well, taking the subterfuge into new territory.

In essence, the offload is simple: run into contact, then slip the ball to a supporting player to keep the attack alive, rather than going to ground and recycling possession. But there’s much more to it than that.

The ball-carrier must deceive the defence, with footwork, by transferring the ball to where it can cause the most mayhem, by lobbing it accurately from height, or slipping it low perfectly while falling in the tackle.

As well, the runner must arrive at just the right time, a split second too early or too late and the chance is gone. Done well, the darkness of even a well-organised defence can be torn apart, even at a Rugby World Cup.

PASS MASTERS

"When Sonny Bill's at his best, he's got an amazing ability to make the right decision in the offload," former All Blacks coach Wayne Smith says. "Sometimes you'll see him halfway to the ground, the ball just about to come out of his right hand, but then he'll hold onto it because he's sighted the support player and he's judged it's not the right time to give it."

All Blacks head coach for two years and assistant for another eight seasons, Smith says others are now as proficient as the pass master.

"There are a lot of players who have copied Sonny Bill, and are just as good as him," Smith says.

Anton Lienert-Brown’s one that comes to mind. He’s a very unconventional passer, but he’s very accurate.

Wayne Smith, former All Blacks coach

Wayne Smith, former All Blacks coach

As an 11-year-old in the south Waikato town Putaruru, Smith was inspired by watching the 1968 All-Japan touring team's attacking style, epitomised by prolific try-scoring wing Demi Sakata.

He now implores his Kobelco Steelers team to play at high pace, keep the ball alive and execute "standing offloads". Most Japanese teams play that way, including Super Rugby's Sunwolves, and former All Black Jamie Joseph's national team.

"The last option [in Japan] is to go to the ruck,” Smith says.

Pacific Island teams are brimful with natural offloaders too. Fiji's Leone Nakarawa, for example, is a 1.98m lock with a flyhalf's handling skills.

Expect to see players of all stripes unleash their inner SBW as the Rugby World Cup continues - and get used to offloading become an even more prevalent and potent form of attack if World Rugby go ahead with plans to lower the tackle height.

KEYS TO THE OFFLOAD

Execution is vital to a successful offload.

Smith says the skill requires constant practice and a high level of awareness from support players.

"You've got to be careful with the mindset or it can be taken as an opportunity for players just to chuck the ball around. That's not what it is at all, it's a valid strategy as long as you're really accurate with the offload to get that really quick ball, or to get the ball away and to make small breaches in the line, but you've got to be accurate, that's the key thing.

"It takes a bit of work to get players using footwork. You've got to actually win the contact before you make the offload. If you go into a contact thinking 'offload', often you'll be caught high, maybe with a foot off the ground and you'll be giving away the cue that you are trying to get the pass away."

The offload can be done many ways - a traditional pass, a pop over the top or out the back of the hand.

"If you watch Sonny Bill, or Anton Lienert Brown, they are always sighting the receiver out the corner of their eye. Just as the pass is subtle and hidden, it's still within that rule of having to see the receiver longer before you give him the pass."

Supporting players have to maintain the right depth to make an offload effective.

"Every support player should know every characteristic of the ball carrier. If you are supporting Sonny Bill and he offloads out the back of his right hand to his right hand side, you need to be pretty flat on him. It's going to be a flat ball, so that determines your depth.

"If he's going to pass to his left-hand side, he still generally passes out of his right hand and goes around the back of the tackler, so you need a wee bit more depth to be able to receive that ball because it takes longer than the one out the back of the hand."

The best offloaders are more than one trick ponies.

"The more the defence is thinking 'gee this guy could pass or he could offload', the less chance they get to put two or three tacklers into that tackle because they're having to mark up on the players around that ball carrier. Being able to pass before and after the tackle is a really effective way to make sure only one man is tackling you. It's a chance to do all those options or get really quick ball off the ruck."

Lee Smith, a former NZ Rugby coaching director and former International Rugby Board development manager, says the All Blacks could use the tactic more.

"It's an opportunity for New Zealand at the World Cup. Everyone has copied our war of attrition style, based around carrying hard to the gainline and recycling the ball.

"One of the problems I see is the existing players are comfortable the way they are playing now. The closer they get to the World Cup, the less likely they are to change the war of attrition approach, so long as they are being successful."

Offloading isn't all that high-risk, he says, because the attacking team will generally have "an Indian file" of support players, allowing them to quickly recover if an error is made.

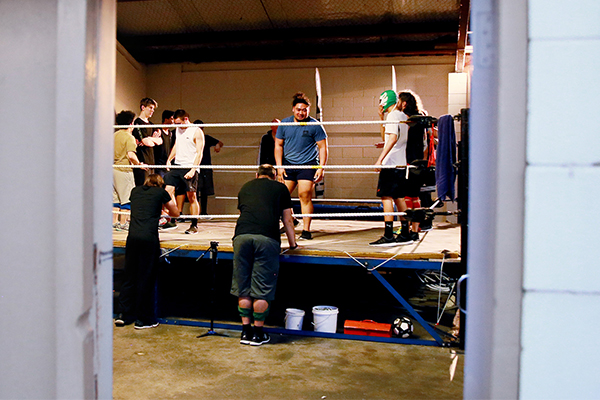

THE SBW WAY

Offloading became prized by the All Blacks six years before Sonny Bill Williams first pulled on the black jersey, Smith says.

It became integral to the game plan when Smith and Steve Hansen first worked under Graham Henry in 2004.

"It was such a key strategy that we decided to put a 7 on the end of all of our calls - 'Canterbury 7' etc. What it did was remind the ball carrier to try and keep the ball alive, either before the tackle or in the tackle with Richie McCaw.

"We saw the offload as an opportunity to change the point of attack and get the ball carrier into a weaker tackle, which then allowed you to get the ball live again or go for a really quick ball from the ruck, compared with a ball carrier being hit by two tacklers."

The All Blacks' commitment to continuity was underlined by a brilliant 47-3 win against France in Lyon in 2006. Lock Ali Williams showed his flashy backs the way to offload, slipping a peach of a pass for Conrad Smith to scamper 80m to score.

But Sonny Bill Williams added a different dimension when he became an All Black in 2010.

A loose forward, second row or centre in rugby league, he found a niche in the All Blacks backline.

At 1.94m and 108kg he is built like a No 8 or blindside flanker and is a more bruising prospect for defenders to shackle than most test midfielders. Williams had to make do with short cameo stints at the 2011 Rugby World Cup, playing just three minutes in the semifinal (after a yellow card for a no-arms tackle on the Wallabies' Quade Cooper) and four minutes in the grand final victory over France.

He had shown glimpses of his potential, with two offloads in his left wing role in the quarterfinal win over Argentina.

Williams spent the 2013 and 2014 seasons back in the NRL. That sharpened his offloading skills and, by the time he returned to the All Blacks for the 2015 Rugby World Cup, he was the world leader in the art.

Former Waratahs and Scotland coach Matt Williams wrote in The Irish Times that the best offloaders in the early 2015 pool games were Williams, Folau and Burgess.

"While this does not sit well with the [rugby union] purists, these great athletes have been coached about the footwork, mindset and decision-making required to pass after contact."

It's a skill, Williams wrote, which requires constant practice. "If you want to play in the National Philharmonic Orchestra, you must play your scales every day."

Former England rugby league coach Steve McNamara, who worked with Williams at the Sydney Roosters, wrote in The Times last November the All Blacks were "a brilliant rugby union team to watch, with all the skills to match, but they are certainly more dangerous with a weapon like Sonny Bill's offload than without it.

"In rugby league, you tried to get three tacklers on to him, one of them over the ball, but because he's so big it's virtually impossible."

With two in the tackle, "he can get an arm free easily" and, "if it's one defender, well 99 per cent of the time that's impossible, he just runs over them."

But McNamara says Williams' footwork makes him surprisingly quick and agile, thanks, in part, to his boxing background.

For such a big, powerful fella to change direction how he does is staggering.

Steve McNamara, Former England rugby league coach

Steve McNamara, Former England rugby league coach

Williams, according to The Times, made 38 offloads between 2017 and the November internationals in 2018. But, he wasn't alone. There has been an explosion of offloading since the last World Cup - at all levels of the sport.

OFFLOADING’S ORIGINS

So when and why did rugby become so interested in the offload, a tactic rarely sighted when Wayne Smith played international rugby between 1980 and 1985?

Back then, there was more emphasis on drawing a defender and passing. Players were coached to get good foot speed, to shift the ball before the tackle, or get quick ruck ball. "Rucking was the way you played in those days," Smith says.

"It was more a game based on grouping and spreading rather than continuity provided by an offload.

"Maybe the odd time when there was a single tackler in a wide channel and no-one else around, you'd see the odd pop-up."

Hika Reid, pictured chasing Nick Farr-Jones in a Bledisloe Cup test, scored against Wales in 1980 after an offload by a grounded Stu Wilson.

Hika Reid, pictured chasing Nick Farr-Jones in a Bledisloe Cup test, scored against Wales in 1980 after an offload by a grounded Stu Wilson.

Smith remembers All Black wing Stu Wilson on his back as he popped up a pass for Hika Reid to cap a sweeping move for a superb try in the All Blacks' 23-3 win over Wales in the 1980 centenary test in Cardiff.

"The ability to pass in the tackle off the ground was outlawed after that test, and only came in again more recently."

Historically, France favoured the offload more than most rivals. Pierre Villepreux, France's prodigious long range goalkicking fullback from the 1960s, championed the continuity game - or "total rugby" as it was termed - as Toulouse coach in the mid-1980s.

Villepreux's mantra flowed through to the national team.

Offloads featured prominently in some of France's most memorable tries before the dawn of the professional rugby era.

The ball passed through 11 pairs of hands before fullback Serge Blanco scored the try which clinched France a win over the Wallabies in the 1987 World Cup semifinal. Loose forwards Dominique Erbani and Laurent Rodriquez and pacy wing Patrice Lagisquet all produced offloads.

Then there was the famous Try From the End Of The World to France's Jean-Luc Sadourny in 1994, the last time the All Blacks lost at Eden Park. There were offloads in contact by wing Emile Ntamack and flankers Abdel Benazzi and Laurent Cabannes as France surged almost 80 metres to score.

Offloads began to be seen more frequently in southern hemisphere rugby union after the game went pro in 1996 and the flow of rugby union players to rugby league became a two-way trade.

Rugby league's unlimited tackle rule meant retaining possession was paramount for decades. Offloads were too high-risk.

The move to a four-tackle set in 1966 (later increased to six tackles in 1972) encouraged more rugby league players to shift the ball in contact to wrongfoot defences.

Artie Beetson

Artie Beetson

Artie Beetson, a big, ball-playing Australian test forward between 1966 and 1977 and Queensland's first State of Origin captain, turned offloading into a potent attacking weapon.

He was followed through the decades by scores of inveterate offloaders - from Steve (Blocker) Roach in the 1980s, through to Gorden Tallis and beyond.

The Wallabies rugby union team's offloading ability increased commensurately when former rugby league players such as Andrew Walker, Matt Rogers, Wendell Sailor and Lote Tuqiri switched codes.

New Zealander Corey Harawira-Naera is the top offloader in the NRL in 2019.

New Zealander Corey Harawira-Naera is the top offloader in the NRL in 2019.

Offloads continue to be important in the NRL today. In the just-completed 2019 minor premiership, the Bulldogs' New Zealand-born second rower Corey Harawira-Naera led the charts with 59 offloads from the Broncos' Tevita Pangai with 55 and Andrew Fifita (Sharks) and Junior Paulo (Eels) on 52.

OFFLOADING IN A NEW ERA

World Rugby is under pressure to make the tackle safer with clamour growing after the death of four young rugby players in France in 2018.

France has introduced a World Rugby-sanctioned trial whereby tackles above the waist and two-player tackles will be banned in amateur leagues.

If the tackle height is ultimately lowered, will it make offloading an even more attractive option?

"Absolutely," says Wayne Smith.

A low tackle allows you to use your offloading skills.

Wayne Smith

Wayne Smith

Lowering the tackle height would put more onus on defenders.

"One of the challenges of the low tackle is going to be getting enough foot drive into those tackles so the last thing the ball carrier is thinking is trying to get the ball away. If you hit them hard enough and drive them backwards, they are thinking more about self-preservation or getting a good ball placement."

If the law is introduced and refereed strongly Smith says there will be "a lot more work put into low tackles and ... trying to turn a chop tackle into a dominant tackle".

That could include defenders tackling "just underneath the ball" to "force the ball up with your shoulder". "It's quite an effective way to avoid the offload."

Wayne Smith says teams and tactics always adjust to law changes.

"There will be ways to get your defenders to take their eye off the ball and look at the potential receivers of the offload.

"Every time there's a law change, there's a reaction to it. That will happen again."

Words: Tony Smith

Visuals: Getty Images

Design & layout: Aaron Wood

Editor: John Hartevelt