Decades before we knew climate change was anything to worry about, a community was built over water in South Dunedin. Now, as it rises around them, ‘water’ is a fearful word for the people who live there.

The rain started just before the sun rose, and didn’t stop for 24 hours.

It was one of those floods when, if you were exposed to it, you remember the year, the month, the day, a long time afterwards; one of those events that marks a change in the social fabric of a community, that only becomes apparent after the roads have re-opened, after the sodden carpets have dried.

They keep you on edge any time it rains, when the gutters start to pool and it threatens to start all over again.

For the southern suburbs of Dunedin, one of those floods began on the morning of June 3, 2015. A low pressure system from the south had been expected to cause “persistent rain, heavy at times” across coastal Otago, MetService had said that morning, but the rain proved to be more intense than forecast.

By around midday, a month’s worth of rain had already fallen on coastal Otago. The same amount had fallen again by 6pm, and once more by 6am the following day, when it finally stopped. In South Dunedin, over the course of the day, flooding had caused ponding up to half a metre deep in some streets, floodwater likely contaminated with sewage spilling into houses and businesses.

The army was called in to help sandbag coastal homes, and one of its Unimog trucks was sent to evacuate children from a primary school. A retirement home was ruined, and its residents, some of whom had dementia, were unable to return for months.

When all was said and done, around 1200 homes and businesses were damaged by water. Insurance payouts topped $28m, but the cost of the event was much higher. Insurer IAG estimated the economic damage at $64m and the social damage at $18m, a combined cost of $138m.

The flooding was not just severe, but unfairly so. It was as though circumstances had conspired to direct the damage where it would do the most harm, a consequence of incremental decisions made over the course of a century.

Most of Dunedin is hilly. Houses were built on the low, jagged slopes of an extinct volcano, from where they looked over the harbour and the freshwater marsh, the swamps and the dunes on the shore, an area that came to be known as “The Flat”.

This 1864 illustration by Andrew Hamilton, ‘Dunedin from the track to Anderson’s Bay’ shows how the South Dunedin community was built on swampy terrain. (Hocken Collection - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago)

This 1864 illustration by Andrew Hamilton, ‘Dunedin from the track to Anderson’s Bay’ shows how the South Dunedin community was built on swampy terrain. (Hocken Collection - Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago)

As the city grew, primarily on the back of the gold rush, it repurposed those flat but swampy areas south of the city centre for housing. The housing was of low quality, with dubious foundation. The swamp was filled with whatever filling material was on hand, usually sand, and filled to only slightly above the water table.

The Flat became one of the most densely populated areas in New Zealand, and remains so; some of the old miners’ cottages, shoulder-to-shoulder on narrow streets, are still there on tiny sections.

When The Flat was developed, it probably wasn’t understood that a flat area by the sea, beneath a large, hilly catchment area, functions as a basin. It might not have been a problem until the population grew and the ground was paved with asphalt, and modern life necessitated the use of water that needed to be disposed of within the restrictive laws of gravity, meaning this water, with or without human intervention, would inevitably travel downwards.

And so on June 3, 2015, from about 5am, the water rushed downwards. It pooled in the open parks, the sports fields, and the school grounds. The network of pumping stations and drainage pipes, many decades old, were not up to the task. Thousands of people in South Dunedin awoke to a flooded city, and a grim omen of the future.

On a bright Winter’s day in June this year, four years after the floods, a giant drill bore down into the Earth.

The threat of climate change, and how it is likely to affect South Dunedin, has exposed how little was known about a place that became home to more than 10,000 people and billions of dollars worth of infrastructure.

What happens on the surface during heavy rainfall is no secret - it floods gratuitously. But how is that shaped by forces deep below the surface, which are far less obvious, but no less significant, to the fate of South Dunedin?

Hence the drill. Its purpose was to drill downwards, essentially as far as it could go, through the thick sediment, the salty groundwater, and into the bedrock. It collected data about the different layers of sediment, and how the groundwater moves through them; all crucial evidence that, until now, has been a mystery.

Until fairly recently, if you were walking around South Dunedin, you wouldn’t know, for example, what the depth of sediments was between you and the bedrock below.

“We’re really trying to fill in some of those basic, first order questions.”

If adapting to climate change is a maunga New Zealand must climb, the greater South Dunedin area is its Aoraki. It is a tangle of physical, social, and economic components, all of which bounce off each other in complex ways.

This collision of different spheres – scientists and engineers and social researchers and politicians and community advocates – is a case in point for the complexity of learning to live with the effects of climate change.

The people who live in South Dunedin already recognise this complexity in their lived experience. Its most obvious form is a long-known geological quirk in the South Dunedin suburbs – if you dig into the ground, you don’t have to go far to find water.

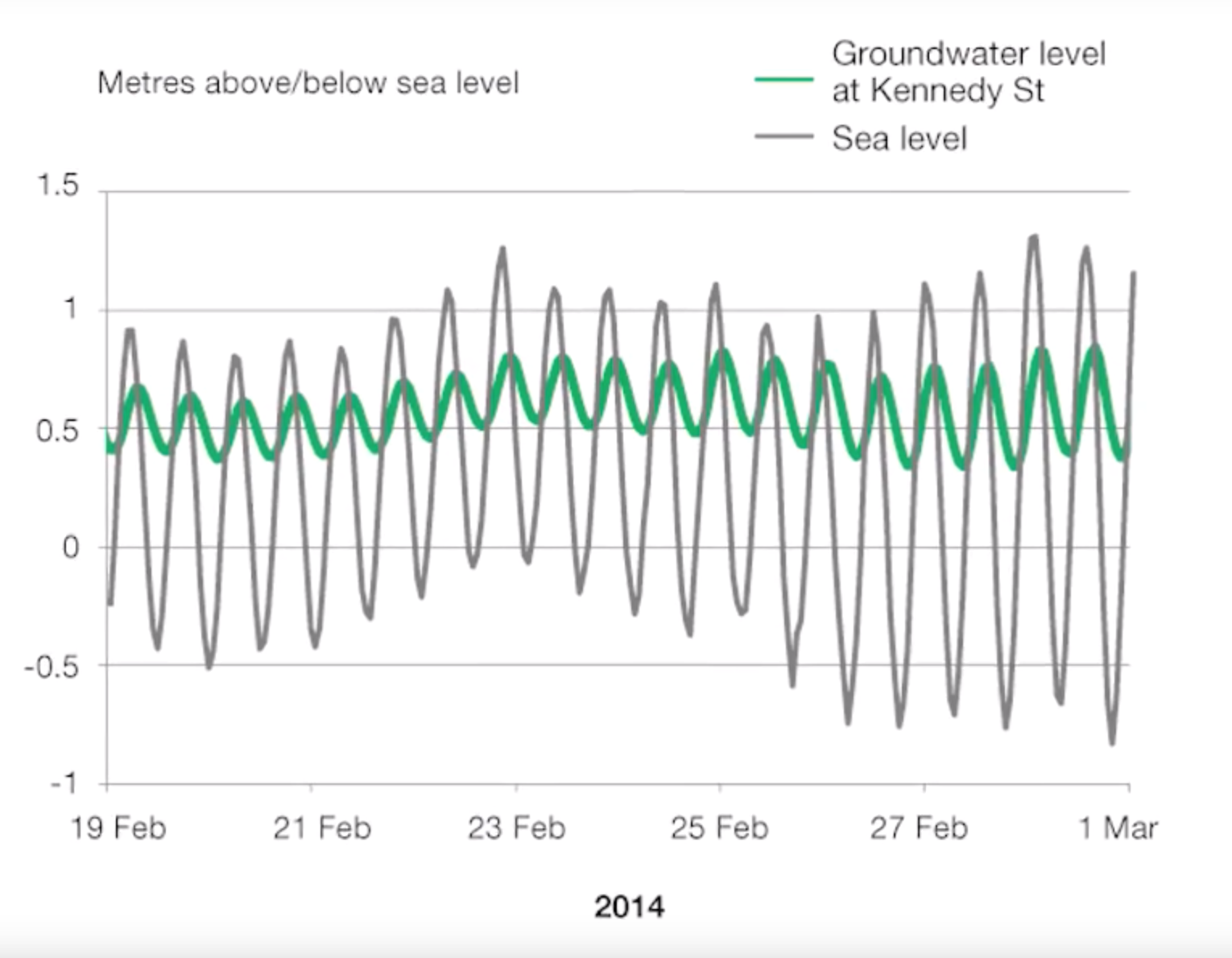

The water table is not just high, but unusually so, to the point where modest amounts of rain can cause flooding. And unlike most aquifers, the water table is, at least in part, connected to the sea – when the tide rises, so too does the groundwater.

Groundwater levels go up and down with the tides. (OTAGO REGIONAL COUNCIL)

Groundwater levels go up and down with the tides. (OTAGO REGIONAL COUNCIL)

It’s as though the community was not built by the sea, but on top of it. There are stories of builders waiting for low tide to dig foundation holes, and of gardens dying due to the salty water pooling after modest rain.

“It’s very obvious to me there’s a problem, as it is for a lot of people,” says Eleanor Doig, who lives in low-lying Musselburgh.

“You say the word ‘water’ around here and everyone gets anxious.”

The water is inescapable, she says. Two years ago, it became so bad she put in drains and a pump at her home.

“Up until then, I had to walk out to the washing line with gummies on,” she says.

“Even if it was just rain, the water would be halfway up my gummie… We’ve had to raise our flowerbeds because the soil is saline.”

It’s not just the high water table. South Dunedin, like a lot of dense urban environments, is impervious – all the concrete and other hard infrastructure stops water from seeping into the ground. As a whole, South Dunedin is 60 per cent impervious, but some pockets reach 100 per cent. When it rains, the water has nowhere to go, and must be manually removed.

Because it is a basin, this water is topped up by rain bouncing off the hills. Even if the water can be absorbed, when the water table is high, the water has nowhere to go. It rises upon itself, onto the surface and into the lives of thousands of people living there.

Climate change factors into this in a few different ways. First, the connection between the groundwater and the sea. Sea-levels are certain to rise – at least modestly, and potentially catastrophically – which, if reflected in the groundwater beneath South Dunedin, presents an obvious problem.

At its lowest points, some parts of South Dunedin are within 30cm of the water table, and much of it is within one metre. On top of this, it appears the land is sinking by around 1mm a year, adding to the rate of relative sea-level rise.

How and where this causes flooding to happen is not as simple as one might expect, says Dr Simon Cox, a principal scientist at GNS Science.

Track manager Ken McFarlane surveys flooding on the northern bend at Forbury Park Raceway during the 2015 floods. (TAYLER STRONG)

Track manager Ken McFarlane surveys flooding on the northern bend at Forbury Park Raceway during the 2015 floods. (TAYLER STRONG)

He has been studying the water table beneath South Dunedin, and says it would be wrong to think of it like a bath, slowly filling with water until it floods over the top. His work shows the Dunedin aquifer is different. It has a rigid shape, which accentuates when it rains and in response to the tides. It sloshes around, higher in some areas and lower in others, being pushed around by the sea.

It means the way the aquifer looks now may not be how it remains, once the sea more forcefully asserts itself.

“We’ve learned it’s a bit harder than we thought it would be,” Cox says.

“It’s very different from looking at a normal aquifer. A normal aquifer would perhaps be made up of gravels and have a lot more variability and quicker responses to changes from rainfall.

“The challenge for us is to figure out what the shape of that is going to look like as it gets pushed more and more from the coast, and where it starts to emerge through the ground and cause springs and get closer and closer to the surface.”

For people on the surface, this means it will be difficult to predict where groundwater flooding is most likely to happen.

That all of this work is happening now, instead of a long time ago, means scientists are playing catch-up. Until recently, there were only four groundwater bores in South Dunedin, all installed within the last decade. There are now 17, each of which records groundwater levels every 10 minutes.

In the near future, this data could be used to model the probability of groundwater flooding in particular areas, an exercise similar in nature to weather forecasting.

“It’s fair to say we know an awful lot more than we did two years ago,” Cox says.

“There’s something like $2b of assets in South Dunedin. If you were going to spend $2b in assets in this day and age, new, you would do a lot more investigation into the ground than we have to date to make sure you understand it before you put that investment in place.”

The natural environment of South Dunedin is complicated in itself, but there’s another layer to add on top.

Floodwaters bursting up through a road during the flooding in 2015. (HAMISH McNEILLY/STUFF)

Floodwaters bursting up through a road during the flooding in 2015. (HAMISH McNEILLY/STUFF)

Like most urban environments, South Dunedin is underlain by pipes. Because the water table is so high, the pipes are, in some places, ensconced in water.

The pipes are old, which means they leak. This may, strangely enough, be a good thing, at least in one way – it is likely the high groundwater is being drained by these leaky pipes. It raises the possibility that upgrading the network could be a hindrance, rather than a help.

It also means that combined with the pumping at the surface, South Dunedin has been kept artificially dry for a long time, which may have concealed the severity of the problem.

“Once that [pipe] network is at saturation, overland flow can happen,” says Jean-Luc Payan, natural hazards manager at Otago Regional Council.

Because it’s relatively low-lying, the groundwater, in some places, is quite close to the surface. The complexity is that all those components interact with each other. Understanding that interaction is key in terms of mitigation or just understanding what can be done.

It’s part of the regional council’s job to figure out how to respond to natural hazards, and for South Dunedin, the effects of climate change are a major one.

Under most climate projections, not only will the sea-level rise, but rainfall volumes are expected to become more intense, increasing the probability of events such as the heavy rain that caused the 2015 floods.

Eleanor Doig tells a story about South Dunedin. It was the 1980s, and some of the city’s leaders saw the community as a problem.

“They tried to get a library here and a city councillor turned to the person pushing for it and said ‘do you really think they’d use a library out there?” Doig says.

She sighs.

This community has been neglected for generations.

Doig is a community facilitator, and says the community has long fought against preconceptions about its residents.

It partly comes from traditional economic and social measures, on which South Dunedin performs poorly. On the deprivation index, a measure of socio-economic disadvantage, parts of South Dunedin score in the bottom 10 per cent nationally. The median personal income is $20,100, but in some pockets the median is as low as $14,000. The majority of people do not own the home they live in.

Because it is flat, many South Dunedin residents are wheelchair users, or have mobility issues. Its high density of support services draws people who have experienced mental or emotional distress. The low-quality housing stock makes it affordable for people on low-incomes, or recent immigrants to New Zealand.

It is beneath all of this that the water rises.

But South Dunedin is not just a list of statistics, Doig says. It is also a place with a strong sense of community, with deep historical roots and a diverse population. There are schools, and social groups, and churches; there are parks and sports teams and businesses. People from around the city come to enjoy the beach, or visit the mall, or simply to enjoy the sea wind as it blows pleasantly up the main street.

For community leaders like Doig, the water problem has become central to their work. In recent months, there have been half a dozen hui about the rising water, the most recent of which drew upwards of 130 people.

It’s partly to acknowledge their shared reality and the gravity of the problem, but also to make sure as many people as possible get to be part of the process for finding a solution.

“What we’re trying to do in these hui is say we are determined that no one sitting in Wellington, or at the city council, will make decisions without us being a part of that,” she says.

In the past, South Dunedin has been treated passively, particularly by those in Government. Doig recalls working in the community in the era of Rogernomics, when benefit cuts hit South Dunedin hard.

“There was a sense of frustration and rage in this community that I was scared of,” she says.

“It needed only a spark to set the whole thing off.”

This time, she hopes, will be different. The rising water could provide a chance for South Dunedin to shine, to harness the endurance and ingenuity of its residents towards proactive solutions, paving the way for others to learn how to live with the effects of climate change.

“As well as the threat, there’s opportunities here,” Doig says. “We've got the opportunity to do some creative, innovative urban design.

“We’re arranging more and more events where people get together and grow that sense that this isn’t a hopeless case, this isn’t a terrible community, we’re a poor community but we’re survivors, and we’re a community worth working in.”

A few months after the 2015 floods, then Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Dr Jan Wright released a report into sea-level rise.

It made particular mention of South Dunedin, and the flooding it had sustained months earlier.

It made it clear that South Dunedin was the single biggest community in New Zealand exposed to sea-level rise, at least in the medium term.

The report found around 9000 homes nationally were within 50cm of the mean high tide mark, 2700 of which were in Dunedin, more than Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch combined.

Of those 2700 houses, the majority were within 25cm of the water mark. Some houses in South Dunedin are actually below sea level, protected by the dunes at St Clair beach.

What happens in South Dunedin is nationally significant. Whatever happens there may, for better or worse, become a model for the rest of the country. And what makes the flooding at South Dunedin such a thorny problem is that it’s not just a scientific puzzle, but a social one.

Researchers at the University of Otago have been exploring these issues, and say there are many barriers that need to be overcome.

“There’s an archetype of South Dunedin, as people tend to see it – a low socio-economic area – but just like any other place, people love it for a range of reasons,” says Dr Janet Stephenson, head of the Centre of Sustainability at the University of Otago, who researches community adaptation to climate change.

“That sense of attachment and passion is something we have to take into account when we’re looking at climate change impacts.”

The researchers put together an interactive map in which they could overlay social and economic data with a height above sea-level map, to see if there was a correlation.

There is. The areas closest to sea-level tend to score highly on the social deprivation index, meaning its residents are likely to have low incomes and to be renting their homes.

They also looked at facilities such as schools and community centres, and found 17 such places in the lowest-lying areas, as well as three rest homes.

In discussions about adapting to climate change, there’s a tendency to jump straight to managed retreat, Stephenson says. This can be particularly damaging in places that have traditionally been marginalised, and it’s something decision makers need to keep at the top of their minds.

“Adaptation is, first and foremost, an issue of emotions. It is emotive to be affected, it is emotive to think about the implications for you and your daily life, for your children, for the possibilities of what you might have to deal with in the future,” she says.

It is really, really nerve wracking for people and destabilising and we have to think about that.

Her research showed that councils around the country were not adequately prepared for such conversations.

The recent past has been littered with failures and false starts for councils which have tried to tackle these issues.

It began, most notably, with the Kapiti District Council’s plan to put hazard warnings on many coastal homes that ended up in a prolonged and expensive court battle.

A similar fight took place in Christchurch in 2015, when residents objected to coastal hazard maps that showed thousands of homes at risk of inundation. The maps were dropped and redrawn.

These examples have filtered down through local government, which has collectively struggled to talk about climate change in a meaningful way, Stephenson says.

South Dunedin may prove to be a new model for how councils and communities work together – sharing power and decision making, and navigating the unknown together.

“With climate change, there is uncertainty about the scale of impact, there’s uncertainty about the time-frame, there’s complete uncertainty about what the solutions are,” she says.

“Council staff find it really difficult engaging in such a field of uncertainty, where they’re going into a space and saying we know there’s going to be an impact, but we don’t know how big it’s going to be, and there will have to be solutions but we don’t know what they are yet.

“The earlier the councils start engaging about these questions, and getting the community to co-develop the solutions, the better.”

On higher ground, in the Octagon at the city’s centre, the Dunedin City Council has a lot to mull over.

After the 2015 floods, there was a breakdown in trust between the community and the council. The dispute was somewhat complicated, but it centred around whether the extent of the flooding was inevitable, or had been exacerbated by poor management of South Dunedin’s infrastructure.

The council had been quick to attribute the flooding to the sheer amount of rain; the day after the rain stopped, then mayor Dave Cull cited climate change as a potential contributor to the flooding, and floated the prospect of managed retreat at some point in the future.

A newly-formed community group, mostly comprising retired engineers, objected. They said the flooding was less about climate change and more about neglect of the drainage system, which they believed should have coped much better.

There was truth in both arguments. At the height of the heavy rain, there had been a malfunction at a pumping station, causing water to build up. A later analysis found this had added around 200mm to the flood level, a not insignificant amount.

But it was a lot of rain, by any definition. According to a rain gauge at Musselburgh, it was the most rain recorded in a 24 hour period since 1923. The view would seem to be bolstered by major floods since; one in February 2018 flooded houses and prompted a state of emergency, while another in November 2018 caused widespread surface flooding.

A famous photo of a boy in a row boat at the flooded, southern end of Normanby Street, April 1923.

A famous photo of a boy in a row boat at the flooded, southern end of Normanby Street, April 1923.

The same street today, during normal conditions. (GOOGLE STREETVIEW)

The same street today, during normal conditions. (GOOGLE STREETVIEW)

In any case, it led to a significant loss of trust between the South Dunedin community and the council. During the months-long clean-up there were angry public meetings, underscored by a sense the community had been abandoned. Cull, in particular, copped blame for his comments about managed retreat.

When we were discussing what the long term options might have been, I was specifically told not to mention the word retreat. Needless to say, I didn’t take any notice.

For his part, Cull maintains that managed retreat remains a possibility, and should be discussed.

He acknowledges, however, that the acrimony during that period was a set-back for both the council and the community.

“We managed to take the conversation forward from there, but that set us back quite a long way.

“I think it delayed a constructive conversation about what the options might be going forward with South Dunedin, because there’s absolutely no doubt there will be areas of South Dunedin under threat of inundation.”

It led to a perception that the solution lies in infrastructure – that bigger, newer pipes are the key to address the problem.

Cull has no time for those arguments. “It’s facile and naive, and betrays a misunderstanding of hydraulic engineering, for a start,” he says.

The issues are far more nuanced, he believes, and will need to be worked through slowly, to ensure the community is on board and isn’t further marginalised in the process.

“The people at the bottom of the barrel are expected to bear the brunt of the cost. Well, no, that’s not sustainable, or conscionable,” he says.

“It’s not going to happen overnight, and the council is going to work with the community as to what our options might be.”

Much of this work will be done not by elected politicians, but by council staff.

There has been considerable discussion within the council bureaucracy about how best to manage the issues in South Dunedin. With little precedent within New Zealand, and a history dominated by failures, the council has been left to go it alone.

Part of the council’s response thus far has been to reckon with the city’s historic relationship with South Dunedin.

“We have people in that area who face a lot of challenges in their lives. In some ways they’ve been left to face those challenges on their own,” says the council’s corporate policy manager, Maria Ioannou.

“For us, climate change gives us an opportunity to see whether we might, through that lens, resolve some of those other issues, like poor housing quality, like the lack of pathways into work.”

The first, most basic task for the council is to figure out how to talk about it. It has required a total rethinking of how a council engages with the community. A normal six week consultation period won’t work for a problem likely to linger for decades, one that is wrapped in layers of uncertainty.

It’s taken a few years, but Ioannou says the door has been opened to a meaningful conversation about the issues.

“At first, no one wanted to talk about it,” she says. “Then people wanted to talk about the extreme scenarios; either everyone stays, or you retreat from the entire area.

“Where we’re at now is really down to the nitty-gritty and working out whether there are pieces of this we can solve now, are there things we can do to make it easier in 20 years? It’s a much more piecemeal, much more nuanced place we’re getting to, but it’s not an easy conversation to have.”

Rather than holding its own meetings, the council has approached existing community groups – like churches and Plunket groups – to speak to people informally, in places where they already feel comfortable.

There is clear progress, she says. The council has reached a place where it’s willing to say there is a lot of uncertainty about the future, that it doesn’t have all the answers, and that it needs the community’s help.

This is not a once and done type thing.

“We’re probably going to be talking about this 50 years from now and we’ll have come some way, we’ll have made mistakes, we’ll have done some things that worked and some things that didn’t. We’re all testing these things out and the more councils share what they’re doing, the better.”

While these high level discussions continue, the people of South Dunedin push for something radical – control over their own destiny.

In the decades to come, the hui will continue, and the community will start to change. Ideas are already being floated – progressive urban design, like canals, and roads that tilt towards the centreline, not the footpaths; redesigned social housing, with rain gardens and other methods of reducing run-off; restoring parts of the landscape to wetlands, constructing raised walkways and adaptable housing.

The future for South Dunedin, at least for now, is to live with the rising sea, not to run from it.

“While the landscape may not change – we might have a 20-year window – things have to be set in place now. And I have a real sense of urgency about it,” Eleanor Doig says.

“There’s a diverse, resilient community here, and we are determined to be involved in our fate. Demographically, it’s at risk, and typically those communities have been ignored. But nuh-uh – no longer.”

This story is part of an irregular series called Frontlines, exploring how communities are adapting to sea-level rise in New Zealand. It was reported with help from the Aotearoa Science Journalism Fund.

Words Charlie Mitchell

Video Journalist Alden Williams

Design Kathryn George

Editor John Hartevelt