Green

Jobs

How to choose a job that will save the climate

Young or old, most people want a career path that will help, not harm, the planet. Olivia Wannan explores the industries that will – finally – make a dent in Aotearoa's emissions.

I’m interested in connecting people back to Papatūānuku, to Mother Earth.

School may be out for the summer, but Rotorua college graduate Kaitlyn Lamb won’t be sitting around waiting for university to begin.

Part of a generation whose working lives will be entirely shaped by the climate crisis and the country’s green transition, Kaitlyn will spend 10 weeks on a project to boost urban farming.

“The main way we’re destroying our environment is through the way we produce our food, which is mostly in mono-cropped farms. There are so many more beautiful ways that we could live in harmony with nature,” the 18-year-old says. “There’s no way we can possibly continue what we’re already doing.”

Her work is part of Bayer’s Youth Ag Summit, a global course for young people interested in sustainable farming.

Kaitlyn Lamb will spend her summer virtually learning about sustainable farming.

Kaitlyn Lamb will spend her summer virtually learning about sustainable farming.

Kaitlyn’s particular passion is healthy soil. In her spare time, the Forest & Bird Youth member teaches composting workshops, organises rubbish clean-ups, plants trees and volunteers on an organic farm.

We already have all the solutions we need to protect our environment and ourselves, in a way. I’m extremely hopeful.

Kaitlyn wants to (eventually) open an urban farm. To get there, she’ll study environmental science at the University of Canterbury, majoring in environmental contamination – which will help her learn more about soil.

Kaitlyn already teaches composting and volunteers on an organic farm.

Kaitlyn already teaches composting and volunteers on an organic farm.

She won’t be lonely. David Trought, a career planner at Clear Path Careers says environmental science is an increasingly popular subject, as young people seek sustainable careers.

“The last two years, there’s been a significant increase,” he says. “They probably view my generation as the ones who mucked it up, and they’re very much the ones to fix it. You can see an urgency: something has to be done.”

Trought says his rural clients are also engaged, with dairy farmers putting together management plans and kūmara growers using technology to maintain water quality.

In his experience, school students are shifting away from particular subjects and industries, such as geology, which can lead to careers in mining and extraction. “People don’t want to be doing something that’s viewed as damaging to the environment.”

Composting both creates healthy soil and reduces greenhouse emissions.

Composting both creates healthy soil and reduces greenhouse emissions.

New Zealand’s transition to net zero will bring change – but careers have always evolved, says Climate Change Commission chair Rod Carr.

“The nature of work has been changing continuously and consistently for the last 100 years,” he says.

“Half the jobs that are being done today weren’t around 30 years ago. So it’s not unreasonable to think that in 30 years’ time, half the jobs we’re doing don’t exist today.”

Green gamechanger

Picture a Monday morning in 2040. People begin work under job titles the people of 2020 wouldn’t recognise. But even the working lives of managers, lawyers and builders look different.

For a start, remote work is common. Rather than commuting, people log on from home, a suburban hub or even a café.

An auditor checks emissions data in the company’s annual report. A manager briefs the Chief Sustainability Officer on greener options for the supply chain before an executive meeting. A builder picks up lower-impact building materials to minimise the “embodied carbon” of the house they’re constructing for an eco-conscious young family.

Lawyers assist clients to understand obligations under upcoming climate legislation. A city planner meets with community members to discuss the resettling of the suburb as the seas rise.

Because of national and international regulation, customer concern and staff values, green practices will become as embedded as health and safety standards, says Sustainable Business Council executive director Mike Burrell.

“I don’t think people have quite got their head around how quickly these transitions will happen,” he says. “That’s going to happen at a pace that is faster than the upskilling of the industry.”

In a previous life, Ellie Lock worked in the fossil fuel industry. She now works in renewable energy and hasn't looked back.

With energy experts concluding that emissions must halve by the end of the decade, it’s likely young people such as Lamb are reading the career tea leaves.

Motu researcher Lynn Riggs also wants to understand employment trends, including the path we’re on today and various routes the Government could take to reach net zero carbon emissions, with the help of economic modelling.

Naturally, some of the model’s headline results are common sense: jobs in the oil, gas and coal industries will start to dry up. Vacancies in factories reliant on fossil fuels – for example, to make chemicals or provide heat – will be scarcer.

Riggs says this doesn’t always spell lay-offs. “It just means that there will be fewer jobs… for example, people leave and aren’t replaced.”

Plus, the model crunches the numbers on industries – not jobs, Riggs explains. An accountant and a payroll officer at a coal company might quickly find new jobs with a bank or solar installation business, for example, even though their current industry will shrink.

The number of forestry workers is expected to grow, compared to today’s workforce.

The number of forestry workers is expected to grow, compared to today’s workforce.

On the other hand, forestry is a safer career bet, with workers increasingly sought after no matter which path the Government takes.

In agriculture, there will be fewer farm hands as dairy and meat animal numbers decline. But this might be partially offset as newer jobs emerge, for example in the distribution of a methane-cutting vaccine.

This trend is already emerging, Riggs says. “If you look at the age of sheep and beef farmers, the average age is pretty high, which is usually indicative of a declining industry with fewer people coming in.”

The Government’s decisions could arrest some of this – the Climate Change Commission’s suggested roadmap actually saves some farming jobs, compared to the path we’re on today (which could see lots more farms replaced with trees).

For other industries, such as trucking, the zero carbon path is a double-edged sword. Truck driver numbers are expected to rise until 2035, as electric vehicles hit the road and diesel fleets use fuel more efficiently. But beyond that, the job losses will start to outweigh the gains.

Next year, the Government will unveil a plan to reduce the country’s emissions. But as the economy is trending towards lower carbon anyway, according to the economic modelling, these new policies won’t be solely responsible for killing particular industries. “They might have accelerated it in some cases, but a lot of the changes were going in that direction anyway,” says Riggs.

On the flipside, investment in renewable generation is growing, as vehicles and heating systems electrify and the Government strives for a 100 per cent green grid. The climate commission estimates renewable plants will generate 37 per cent more power by 2035, compared to 2020. Wind turbines are expected to play a key role.

Generators are also backing geothermal. With some investment from rival Genesis Energy, Contact Energy is building a new station, Tauhara, near Taupō harnessing the earth’s heat to generate electricity.

Unlike wind, geothermal is reliable – humming away all day and all night. But it isn’t completely emissions-free, as the geothermal fluid from underground contains carbon dioxide. To solve this problem, engineers need to crack carbon capture – reinjecting carbon dioxide into the ground. That’s something Contact Energy is trialling. These tasks are job creators.

The more things change

If the country gets the transition right, job evolution will occur at a steady – and survivable – pace.

If the shrinking of an industry is “well-signposted”, says Carr, this is less likely to result in redundancies. “It just might mean you stop recruiting.”

The end of an industry might actually mean more work in the upcoming decades.

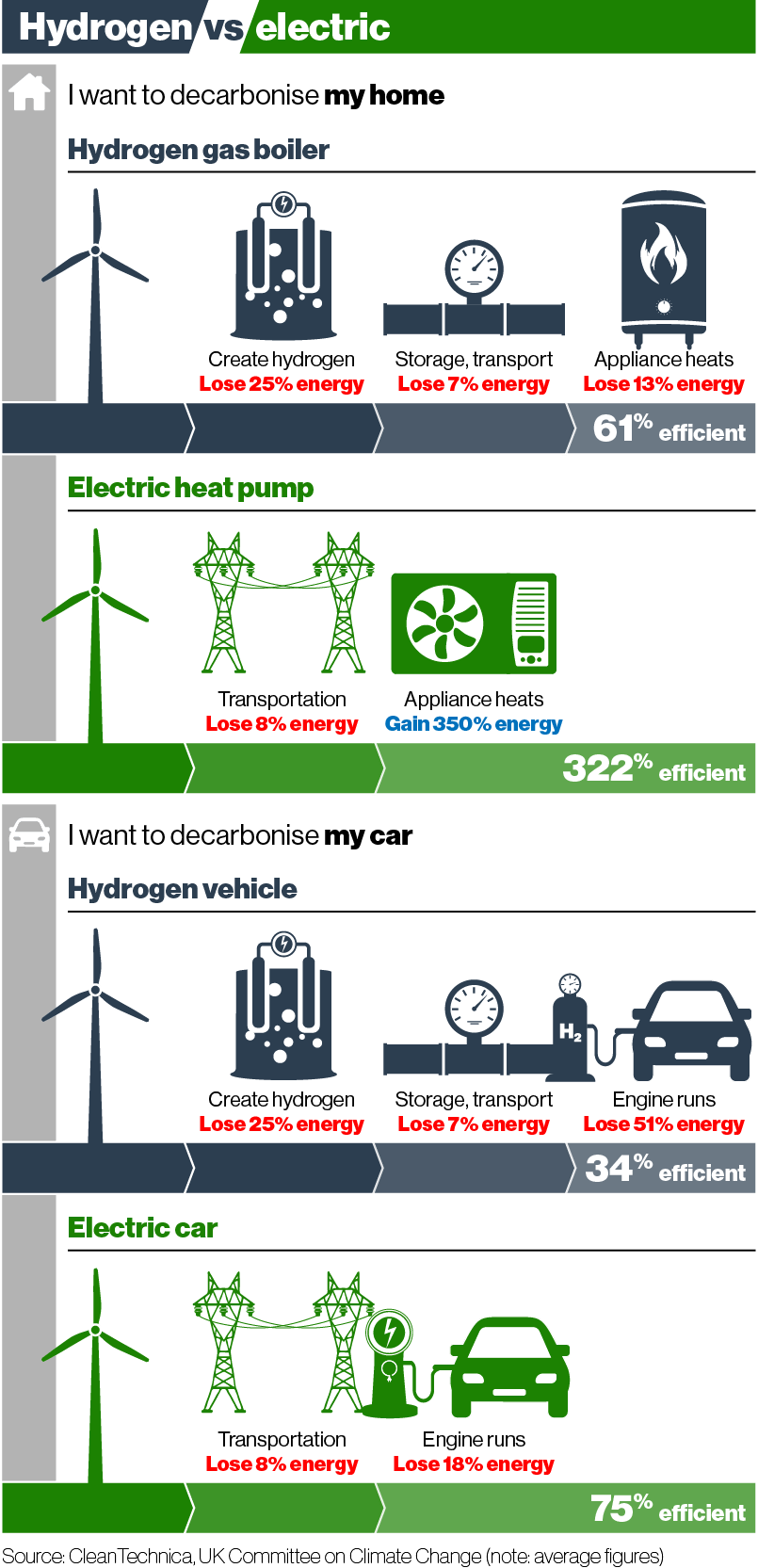

Take gasfitting: the climate commission suggested that homes and buildings should stop connecting to the gas network, because electric tech can provide heating, water heating and cooking right now. The alternatives using gas pipes – green hydrogen and biogas – are not produced at scale.

Climate Change Commission chair Rod Carr says greening the economy stimulates work.

Climate Change Commission chair Rod Carr says greening the economy stimulates work.

Beyond a set date (2025 was originally floated), new gas connections would be installed in exceptional circumstances only.

The Government hasn’t ruled out including a ban in its upcoming Emissions Reduction Plan, but it may take a punt on green hydrogen.

Since today’s gas appliances can only handle a blend of up to 20 per cent hydrogen before they must be replaced, whatever route the Government picks is likely to require gasfitters to visit every gas customer in the country – either to swap the old appliance for electric or to fit a new system capable of burning high levels of hydrogen.

Additionally, the commission recommended that any gas appliance installed before the cut-off should be able to live out its natural life, which can be as long as 20 years.

Unitec’s Simon Goodlud trains gasfitters for a living. He agrees there’s plenty of work for his graduates until at least 2050.

Tradies expect their qualifications will be relevant for about a decade, he says. “That would allow us to continue training to 2040… Potentially at a reduced volume – but it will still be there.”

Goodlud believes both electricity and hydrogen will replace natural gas, though it’s hard to gauge the balance until the Government makes its position clear.

His students are on board with the need for change, he says. “They want to save the planet. They’re young people, some of them are having children. They want to do the right thing, just like we all do.”

Goodlud is excited about the prospect of gasfitters returning to upskill in electrical work and green hydrogen – and hopes to pair with a hydrogen training centre in Queensland.

“I’m in my 50s, and started work in the UK with boilers that still used coal, and then we upgraded to heavy oils and gas,” he says. “To see and be part of a transition from greenhouse gas-emitting appliances and processes to a carbon-neutral process is exceptionally interesting and exciting.”

A long, green to-do list

Carr’s team spent months producing the best estimates possible for which industries would wane under a carbon-cutting plan. Yet he’s the first to say they aren’t a forecast. “From 2030, looking back we won’t have followed that path.”

However, there’s one thing he’s certain of: “There’s no shortage of work.”

“I can’t think of any human skills and knowledge bases that can’t contribute to helping society move at pace to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.”

To cut carbon emissions, engineer Luke Rundle is replacing a fossil-fuelled system with a high-temperature heat pump.

Those in higher-emitting industries can ignore their job title and focus on the skills they can offer – whether that’s a communications strategy, investment expertise or engineering skills.

That’s the shift Venture Taranaki Te Puna Umanga is hoping to make for its region. Taranaki is currently an energy hub of Aotearoa, providing oil (mostly exported) and gas to be piped around the North Island and bottled for the South Island.

Chief executive Justine Gilliland says oil and gas extraction is an important contributor to Taranaki’s economy and the reason some large factories – such as Ballance’s fertiliser factory and Methanex’s chemical-making facility – are in town.

She’s keen for the energy hub status to remain beyond 2050. One idea is that Taranaki could manufacture and pipe hydrogen and biogas through the North Island.

But Taranaki faces competition as the green gas capital. Unlike natural gas, which is concentrated in the region, green hydrogen can be made anywhere there’s renewable electricity, and biogas anywhere near waste.

The region has a few advantages: the expertise in energy training at the Western Institute of Technology at Taranaki (to be integrated into Te Pūkenga), plus a high concentration of engineers with experience in the energy sector, Gilliland says.

Asked what an unjust transition would look like, Gilliland says local towns have already experienced these.

When the freezing works closed in Pātea in the 80s, essentially there was no planning. So that community was really just set adrift. We still see the ramifications of that today.

Leave no one behind

A strong national emissions plan may minimise the pain that workers will face, but redundancies can’t be avoided entirely. The commission expects the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter to close before the end of the decade, with 1000 people – many with highly specialised skills – losing their jobs.

By 2040, Methanex is expected to close, since its plants rely on cheap natural gas to make chemicals. That could put up to 250 people out of work.

Methanex plants make the chemical methanol by combining fossil gas and steam.

Methanex plants make the chemical methanol by combining fossil gas and steam.

It’s harder for a large manufacturing plant to slowly decrease its workforce. Rather than an ongoing trickle from the industry, there will be abrupt changes.

Karen Lavin, a principal analyst with the Climate Change Commission, says the country has an obligation to look after these employees, starting now.

The government must identify employees most at risk of redundancies. For those with easily transferrable skills, it could launch job brokerage programmes, she says.

For people later in their careers, the government could consider paying for their early retirement, Lavin says. Ministers made a similar move in 1989, making payments to waterfront workers when the ports were privatised.

Otherwise, workers should have access to funded upskilling and retraining programmes, while they’re in their current job, she says.

Suddenly being out of a job brings all sorts of anxiety.

“If you can see it coming, you’ve got time to adjust.”

Another hurdle is that employees are naturally drawn to the benefits of their industry, says First Union organiser Justin Wallace.

“Particularly when people have been in an industry for such a long time, they are very protective of it,” he adds. “So when it gets attacked, they get very defensive.”

Yet affected workers understand the need for change and are often fiercely protective of their local environment, Wallace says. “Their kids go to school there, they hunt there, they fish there. They want to retain that.”

Wallace thinks a new minister is required to oversee the green transition and other forces affecting employment.

Meetings with workers, representatives and unions is the next step, he says. “We need to have those conversations. They have been happening, but they’ve been happening sporadically.”

Trade courses are used to offering training around full-time apprenticeships and work. Once, universities did the same thing.

In the 1970s, Carr says, degree programmes started to cater to full-time students, with lectures, workshops and labs during work hours.

“That makes it more challenging if you’re a mid-career part-time student than if you are an 18-year-old school-leaver,” he says.

The issue is on tertiary providers’ minds. The University of Waikato recently launched a new Bachelor of Climate Change. Rather than focusing on climate science, the course will train up business sustainability managers, government policymakers, insurance advisors and farming consultants to implement change.

Programme leader Margaret Barbour had a eureka moment, after thinking that climate science had been taught for decades, all while the world had failed to take action.

“Science on its own can’t provide answers,” she says. “We need to reach outside science… [and] bring in the political, social and social justice issues, Mātauranga Māori and Indigenous perspectives.”

The university is also exploring shorter courses. “Doing a three-year degree might not be that appealing for [some] people.”

Carr thinks the pandemic has opened up universities’ eyes to flexible learning. “It has helped them figure out they can teach at different hours of the day and days of the week, and they can deconstruct their learning programmes into modules. They can teach substantially – but not all, and not every programme – to students who are remote and distanced from campus.”

Just as the jobs of the future may look substantially different from today, so might how we learn to do them.

Green workers today

Olivia Wannan met three employees who love their low-carbon industries.

Renewable engineer Ellie Lock started her career in the fossil fuel industry.

Renewable engineer Ellie Lock started her career in the fossil fuel industry.

Ellie Lock

Geothermal drilling engineer, Contact Energy

Nearly 3000 metres under the ground near Wairakei, a drill grinds through rock to access the heat of the Earth. It’s Lock’s job to monitor, using sensors and imaging, what’s going on down there – so the well is safely drilled, and lined with steel and specialised concrete. No one wants a fissure, which could send scalding liquids up to the surface elsewhere and do some damage.

Lock and her team will drill 11 wells – with rigs running all day and all night – to feed steam and hot water from the ground up into Tauhara station, and down again.

It’s a cyclic process. Whatever we take, we use it to produce electricity, and then we give it back.

In a previous life, Lock worked in the fossil fuel industry. After studying petroleum engineering in Perth, she joined a team in the desert drilling coal seams for gas. Discovering a talent for designing drill bits, she went all over the world on different projects – before she caught the eye of Contact, who invited the famous “Drill Bit Chick” to see their geothermal projects. By day four of her trip to New Zealand, Lock received a permanent job offer, and hasn’t looked back.

“Now I’m part of something that’s making a massive difference,” she adds. “It feels like it’s this small little baby right now, but I can see that it’s a growth industry, and you can tell that it’s going to get big.”

Lock plans to stay in renewable energy – and believes plenty of her fellow engineers could make the switch.

“My advice is to get out early, while you’re young,” she says. “I was all types of wrong on paper for what they were looking for, because I didn’t have any experience. However, I was hired based on my passion.”

Engineers like Luke Rundle of Deta Consulting are – and will continue to be – in huge demand in the coming decades as New Zealand ditches fossil fuels.

Engineers like Luke Rundle of Deta Consulting are – and will continue to be – in huge demand in the coming decades as New Zealand ditches fossil fuels.

Luke Rundle

Project manager, Deta Consulting

After the Government banned new coal boilers and offered money for companies to switch their systems to green energy, Deta’s services are in hot demand. Companies, local government and ministries are approaching the business about replacing fossil-fuelled equipment with green alternatives. Since low-carbon fuels can be more expensive, Deta aims to optimise the entire system first.

Luke Rundle’s latest project is a meat plant, trying to reduce the emissions from its hot water system, which runs on coal and electricity, and its refrigeration equipment.

Rundle completed a degree in chemical process engineering at the University of Canterbury, and worked with Deta in his third year, to complete his professional experience component. He then joined them in a graduate role.

“It’s in the right industry I want to work in,” Rundle says.

It’s an opportunity to improve New Zealand as a whole. You need more people to understand: it’s not a roadblock, it’s an opportunity.

As well as helping the environment, Rundle feels like the industry is at an exciting, innovative point. “It’s massive at the moment… We’ve seen a shift over the last two to three years especially, a lot more focus on decarbonisation.”

Carlos Kershaw calculates how much greenhouse gas a product or company creates, in his role as a lifecycle assessor.

Carlos Kershaw calculates how much greenhouse gas a product or company creates, in his role as a lifecycle assessor.

Carlos Kershaw

Lifecycle assessor, thinkstep-anz

Carlos Kershaw, 22, is self-taught. He was completing his Honours degree in mechanical engineering and working as an intern for Skope Refrigeration when he came across lifecycle assessment. The work helps companies understand the ways both large and small, they create emissions.

He’d heard it mentioned briefly during his undergrad courses, but didn’t come across dedicated courses. At this point, he was starting to realise mechanical engineering wasn’t for him. “I really enjoyed environmental consultancy.”

On an average day, Kershaw meets with clients to discuss a project, gathers data on everything the company consumes and produces, uses software to quantify environmental impacts and write reports. He sees the work as an antidote to greenwash. “We take a holistic approach, looking at the full picture.”

For an office job, there’s a lot of variety. “You’re working with different clients on different projects,” he says. “You’re constantly on your toes. But that makes it more motivating.”

Kershaw is sure he’s made a safe career bet. “There’s got to be a lot more work. If there’s not, then we’ve pretty much admitted defeat [on climate change].”

He encourages anyone interested in the field to complete a project on lifecycle assessment as part of their studies – because employers are looking for someone with a bit of experience. A degree in environmental science or engineering will also help.

Some students complete a detailed lifecycle assessment for their PhD, but Kershaw says this is optional.

If you’re trying to find a job you can feel good about doing, that’s helping with the world’s problems, it’s a good place to go.

...and we're not going to sit back and watch it burn.

Climate change articles like this one are a critical part of how we collectively respond to the crisis of this generation, and the generations to come.

Guarding against contributing to climate change is enshrined in Stuff's company kaupapa. It's our mission to make Aotearoa a better place.

If those values resonate with you, please make a contribution today.