IN THE 10 YEARS SINCE 29 MEN DIED IN THE PIKE RIVER MINE, A FAMILY HAS BEEN CREATED AMONG THOSE DEVASTATED BY THE DISASTER. EACH OF THEM HAS STRUGGLED IN THEIR OWN WAY. THEY’VE NOT ALWAYS AGREED ABOUT WHAT TO DO.

“THERE’S NOTHING MORE INTERESTING THAN A FAMILY,”

SAYS KATH MONK.

“AND WE ARE THE PIKE RIVER FAMILY.”

Trustworthy, accurate and reliable news stories are more important now than ever. Support our newsrooms by making a contribution.

Contribute Now

For Anna Osborne, the thought of her beloved husband Milt trapped in a flooded mine is unbearable.

“Why would I want to leave my husband in a s...-hole that is flooded, in the place that killed him? I want to bring him home.”

Her friend Sonya Rockhouse can’t stand the idea of her precious son Ben being burned. As a 12-year-old, he was badly burnt in an accident. It torments her to think of him burnt again.

Both women do not know what happened to their loved ones. They don’t know why or how they died - fire, water, gas. And as another chapter at Pike River mine draws to a close, they have accepted they probably never will.

The Pike River memorial garden at Atarau, on the West Coast.

The Pike River memorial garden at Atarau, on the West Coast.

Exactly 10 years ago, on November 19, 2010, the women were told an explosion had ripped through the mine where Milt and Ben were working and from which they would not return home.

In the decade that followed they, like many others who lost husbands, brothers and sons in the disaster, have gone from shock and grief to anger, an endless yearning for the remains of their loved ones and a powerful desire for justice.

But what is remarkable about Osborne and Rockhouse, is the disaster transformed them from women whose lives revolved around their families to women who are fighters, campaigners, leaders and lobbyists. They became women who, against what seemed like insurmountable hurdles and in the face of an apathetic public battled on, taking the baton from earlier fighters like Bernie Monk.

And, if winning means anything in this context, they won – to an extent anyway.

‘HELL NO’

It is 10 years today since Osborne first heard news of an explosion at the mine, about 46km northeast of Greymouth, where her husband Milt was working underground.

Ten years since she made it past the mine’s gates, the only family member to make it through that day. Ten years since she refused to leave the mine until Milt walked out. She slept with her head on a table without food or a bed for days, finally giving up her vigil when her teenage children called and begged her to come home.

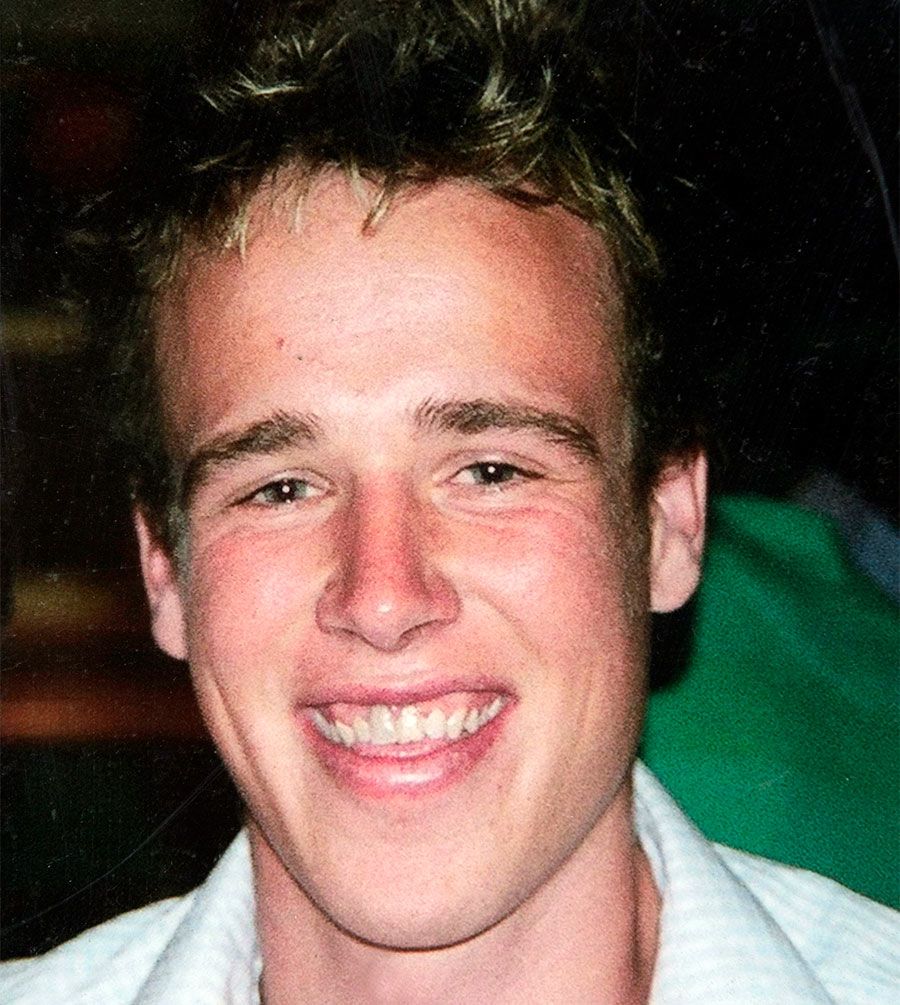

Milton Osborne

Milton Osborne

“I got told I had to leave … I said there’s no f……. way in hell I’m leaving here, not a s... show in hell. I had my arm around the table saying I am not leaving here.”

Osborne expected her husband to emerge from the mine with other miners at any moment.

“I wanted to be there for my husband when he walked out of the mine, thinking he was going to walk over the brow of the hill … Little did I know that I was 8km away from the portal entrance.

“To hear my kids say ‘we need you’, I was so torn because I love my kids but I wanted my husband so much. I stayed and I stayed. In the end I thought ‘I’ve got to go’.”

“ TO HEAR MY KIDS SAY ‘WE NEED YOU’, I WAS SO TORN BECAUSE I LOVE MY KIDS BUT I WANTED MY HUSBAND SO MUCH. I STAYED AND I STAYED. IN THE END I THOUGHT ‘I’VE GOT TO GO’. ”

ANNA OSBORNE

Before she left, she wrote a goodbye message on the whiteboard in the little prefab building where she gripped the table.

“I left a message for Milt and I thanked the miners because I said, ‘I know you're going to bring my husband home to me’ but it didn't happen … it wasn't meant to be.”

On the day she ended her prefab vigil, the mine exploded for the second time, dashing all hope the 29 missing men were alive.

Osborne’s fighting spirit, evident in those early days at the mine, did not lessen in the decade to follow.

She and her close friend Sonya Rockhouse, say they have moved mountains in their search for “truth, justice and accountability”.

Five years ago, devastated no progress had been made in re-entering the mine or recovering the bodies, the pair, both teacher aides, started their own campaign. The government showed no interest in re-entering the mine, and some families had become tired and wanted to quit.

“Anna and I said ‘hell no’,” Rockhouse says, “because nothing had been done. As a mother I felt I had let Ben down because I'm supposed to protect him and I didn’t. So for them to walk away and not even try (to enter) was just not gonna happen.”

Soon after, an upset Osborne called Rockhouse at home in Christchurch. She had heard a rumour the state-owned Solid Energy, which bought the mine in 2012, was sealing its entrance.

Osborne had recently finished chemotherapy for cancer and wasn't well. But she wanted to go to the mine and protest.

Osborne and Rockhouse, side-by-side at a months-long protest in 2012.

Osborne and Rockhouse, side-by-side at a months-long protest in 2012.

Worried about her friend’s health, Rockhouse told her not to go, but Osborne insisted.

“She’s such a worry. I told her, ‘hang on, hang on, I’m coming’.”

The women, eventually joined by hundreds of supporters, started a protest that lasted 107 days.

“We didn’t know what the hell we were doing but people came.”

The successful protest became a turning point in the women’s fight for re-entry.

Inspired by the public support and with the help of the late Helen Kelly and other lawyers who worked for free, the women took their fight for justice all the way to the Supreme Court, winning at the final obstacle.

The Supreme Court ruled in November 2017 that a deal between mine boss Peter Whittall and Worksafe, which entailed Whittall paying $3.41m provided by his insurer into court, was unlawful.

“ YOU CANNOT BUY JUSTICE IN NEW ZEALAND. WINNING WAS A HUGE TURNING POINT. WE HAVE JUMPED HURDLES AND CROSSED RIVERS AND CLIMBED MOUNTAINS TO GET WHERE WE HAVE TODAY,”

ANNA OSBORNE

“Nothing has been handed to us, nothing has been easy.

“We want the families to appreciate how much time and energy we have put into this, how we have struggled, emotionally, physically. We have been tired and drained and ready to walk away but we couldn’t because we weren't just doing this for us, we felt like every family deserved justice and accountability as well.”

The incoming Labour-led Government of 2017 proved pivotal in their fight for re-entry. Before the election, Labour had pledged to enter the mine. The Pike River Recovery Agency was established the following March.

After the “breakthrough”, the women could finally relax and let go. After years of setbacks, someone was listening and something was happening.

Osborne’s daughter Alisha, who begged her to come home from the mine all those years ago when she was only 13, has found it hard to witness her mother’s fight for justice and her struggle with cancer.

“She’s lost so much of her life. The last 10 years she's basically been working unpaid 40-plus hours a week on Pike alone. It’s huge and not fair and I really do want her to start living her life after it's finished, hopefully soon.”

Alisha credits her mum’s dogged spirit partly to her father.

“Mum picked that up along the way. He’s gone, so she’s like, ‘well if this was me, Dad would do this for me’. Dad’s character inspired her because he would do it for her; she knows that.”

After 10 years, Alisha still wants to have a funeral for her father, whom she idolised.

“I want to have a funeral, I keep saying to mum we need to do that. It won't be a normal funeral but he was such a great man that it's a real shame not to celebrate.

“He was just hilarious, everything was just funny, he was serious when he had to be - one of the funniest, most intelligent people you will ever meet. I will never meet anyone else like him in my life, ever.”

She looks forward to the last chapter at Pike River closing, when the mine is sealed after the tunnel is finally explored. She has struggled with the public nature of her father’s death and being powerless to protect her mother from scrutiny and uninformed or negative comments online.

“It's going to be exciting for Pike to finish because those two women [Anna and Sonya] deserve to not have to think about it the way they do now.

“It should be a memory and a time to remember loved ones rather than have to fight for them, so it will be a good day when that happens.”

BERNIE

The work done by Osborne and Rockhouse continued the fight started by Bernie Monk, for a long time the voice of the Pike River families. Monk’s son Michael died in the mine. He remains the leader of a families group which is separate to the effort led by Osborne and Rockhouse - both members of a group liaising directly with the Pike River Recovery Agency.

He was a member of the Pike River Families Reference Group, a body set up to liaise with the re-entry bid started in 2018, but resigned.

He can pinpoint the exact moment he lost faith in the system. Just before Easter 2011, about five months after the explosion, Monk was shown an image taken from a scan of the mine via a shaft. It showed a body lying in front of an open self-rescue box.

“ THAT’S WHEN MY TRUST OF EVERYONE WENT OUT THE WINDOW”

BERNIE MONK

The photo shocked Monk because he had been led to believe no-one could have survived the first explosion.

“This is one of the biggest homicides in New Zealand’s history. And they have not treated it in that way. We’ve been lied to. There’s been cover-ups. There’s been no sharing of information. They’ve ignored the families and it makes me sick and angry that all these people in top jobs have just disregarded the families in this way,” he says.

Monk’s wife, Kath says: “When your child is involved, when it’s your flesh and blood that’s been killed you want to know everything. You want to know the actual truth about what really happened. The truth needs to come out. It’s respect for the men. They deserve that.”

When Monk became the reluctant Pike River families spokesman, he thought it would be over by Christmas.

“Here we are 10 years on. People thought for God’s sake Pike River families move on. You’ve got nothing to get. But we know there are people to get. We’ve seen bodies. We know there is evidence down there. It’s important for this fight to carry on.”

For the first year after the blast, Monk hardly slept and was lucky to get two or three hours’ sleep a night.

Ten years, through 15 government ministers and four Prime Ministers, the fight for truth and justice has taken its toll.

Kath says while they were still grieving for their son, her husband also had to cope with the media and constant pressure.

“... He would be going over and over the same things. Day after day, week after week. And I tired of it. I’d had Pike River up and over the top of me for quite a long time,” she says.

Monk, a publican, stood alongside Pike River battlers Osborne and Rockhouse as they started a protest by blocking the mine access road. He still wants full recovery of the mine workings so he can lay Michael to rest in a place of the family’s choosing.

Michael Monk

Michael Monk

Bernie and Kath say Michael was a quiet, determined boy who blossomed after he went to boarding school at St Bede’s College in Christchurch. A keen sportsman, he developed into a quiet achiever who was in a good relationship at the time of his death. He had bought a section with the intention of building his own house and had been working at Pike River for about five months before the explosions.

“One of the things that really gets to me,” says Monk, “was he relied on those people to keep him safe. They didn’t do it.”

His goal is for the police to admit their failings in the way they handled Pike River from the very beginning; when they did not allow Mines Rescue to take control and later when they did not lay criminal charges.

“No-one has put their hand up and said ‘we did this wrong’. I want accountability. We think people should be convicted for all the wrong-doings particularly what was going on in the weeks leading up to the first explosion.

“You move forward from a disaster like this but you never move on. If the truth had been told right from the word ‘go’ we wouldn’t be in the position we are in 10 years later. Once the truth is out there, I will walk away from this.”

Monk says he withdrew from the Pike River Family Reference Group because he wanted to be able to share information with the wider families, but felt gagged by a non-disclosure document between the group and police.

“Say you’re a family member and you ask me something and I couldn’t tell you. How good of a spokesman am I? I signed a non-disclosure agreement and the only way around it was to resign,” he says.

Kath is philosophical about the differing opinions within the family group.

“There’s nothing more interesting than a family. And we are the Pike River family.”

STU’S MACHINE

Carol and Steve Rose have worked alongside Monk for many years with Carol spending countless hours as secretary of the Pike River families group.

Their deceased son Stu Mudge loved his job at the mine and Carol takes "huge comfort" from the knowledge that her son, a caver, loved being underground.

A friend, who left the mine just before the explosion, passed Stu on his way out.

Stu Mudge

Stu Mudge

“He told us Stu had a big grin on his face. He was happy sitting on a big million dollar machine which he would have loved.

“He is buried in the Paparoa Ranges. We don’t look at it as a black hole we think of it as a beautiful mountain.”

Ten years might have passed but for her, the last time she saw her son feels like yesterday.

“ I WAS JUST LOOKING AT A PHOTO OF STU AND I THOUGHT ‘HOW ON EARTH HAVE YOU BEEN GONE FOR 10 YEARS? WHEN I THINK ABOUT THE FIGHT THE FAMILIES HAVE HAD WITH PIKE RIVER, IT’S BEEN A LONG TIME. IT’S BEEN A LONG, HARD 10 YEARS.”

CAROL ROSE

Along with Monk and the group’s chairman Colin Smith, she was, in 2015, made a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her work on the group which spent almost seven years fighting the National Government and state-owned coal company Solid Energy.

“It got to the point where we couldn’t see any other way, we had hit a brick wall. We were really tired. We had been up against the government and John Key. He wielded a lot of power and it just sucked us dry,” she says.

“Stepping away from that fight was definitely the best thing we could do for us. We really felt Stu saying to us, ‘come on guys it’s time to step away, it’s time for a break’.

“Anna [Osborne] and Sonya [Rockhouse] took up the fight and it was really good timing because they did it in the lead up to the elections [in 2017] and the politicians started listening and then there was the change in Government and the Pike River Recovery Agency (PRRA) was formed. It was fantastic. That new push was a really good thing. I’m grateful Anna and Sonya picked it up when they did,” she said.

Carol and Steve Rose stepped away from the struggle for a recovery mission at the Pike River Mine. But they remain close to the site of the tragedy and involved in memorialising it.

Carol and Steve Rose stepped away from the struggle for a recovery mission at the Pike River Mine. But they remain close to the site of the tragedy and involved in memorialising it.

The couple has bought four hectares in Barrytown, where they will be only 14km from where Stu lies.

They have also been involved with the Department of Conservation to create the Paparoa Great Walk that runs from Blackball to Punakaiki and includes a Pike29 Memorial Track. It was officially opened in November 2019. A 9km stretch that memorialises the disaster will be usable when the recovery work wraps up.

“It has been absolutely amazing to work on something with positivity. It has been fantastic organising and making something really nice come out of the deaths of 29 men,” says Steve Rose.

The track will ensure the families retain access to the mine site.

The Pike29 Memorial Track.

The Pike29 Memorial Track.

“If we hadn’t got the Paparoa Track, the road and bridge access to the mine site would have been lost. The National Government and Solid Energy were going to let it all go and we wouldn’t have been able to go up there. By doing this, the story of the 29 and what they stood for and what happened since will not go away.”

Carol says the fact Osborne and Rockhouse are fighting on one front and Monk on another, can only be good for the cause.

“I feel for Bernie because he’s not had a break. He’s driven. There’s no way we would be where we are without Bernie.”

Steve Rose does not think the recovery mission will find any bodies in the drift but hopes at least one family will get their loved one back.

‘IT WAS NOT AN ACCIDENT’

One of two workers who walked out of the mine alive 10 years ago, Russell Smith is a long way from getting over the disaster.

“I try not to show emotion in front of anybody. It’s more the nights I can’t sleep thinking about it all the time. That’s when it gets you, when you’re trying to sleep.”

Smith, a coal cutter, was late for work and driving a loader with a sticky accelerator up the 2.3km drift (the tunnel to the worksite) when the blast hit him at the 1500m mark. He was helped out by fellow miner Daniel Rockhouse. But for those bits of luck, he would be dead.

Russell Smith with his loader from the explosion inside the Pike River mine.

Russell Smith with his loader from the explosion inside the Pike River mine.

In August, Smith watched the loader being removed from the mine by PRRA staff. The smell of burnt diesel brought back memories.

He remembers washing his hair over and over again trying to get the smell out after the explosion.

Smith, who now works in a meatworks, still thinks of the mine as a crime scene. He remembers a high turnover of staff, particularly managers. He also remembers reporting incidents and being ignored.

He believes the buck should have stopped with the Department of Labour whose inspectors failed to shut down the mine.

“People say the families should let it go. You would let it go if it was an accident. It was not an accident. You don’t kill 29 people and then say no one is actually accountable. That’s what gets me.”

Ten years on, Smith is transported back to the day as if it was yesterday.

“ I FELT IT FIRST. IT WAS A BIG WAVE-LIKE SMACK IN MY FACE. IT WAS EXTREMELY LOUD AND BLEW MY HELMET OFF. EVERYTHING WENT WHITE LIKE A BIG FLASH.”

RUSSELL SMITH

He ducked behind the door of his loader, heaving for breath. As the explosion sucked oxygen out of the mine he began suffocating and collapsed.

As the oxygen began to flood back, he began to come around just as Rockhouse was making his way out.

“He grabbed me by the hair and my eyes were starting to roll around in my head,” he says.

When the two emerged from the tunnel 85 minutes after the explosion, incredibly, no-one was there to meet them.

FINDING OUT

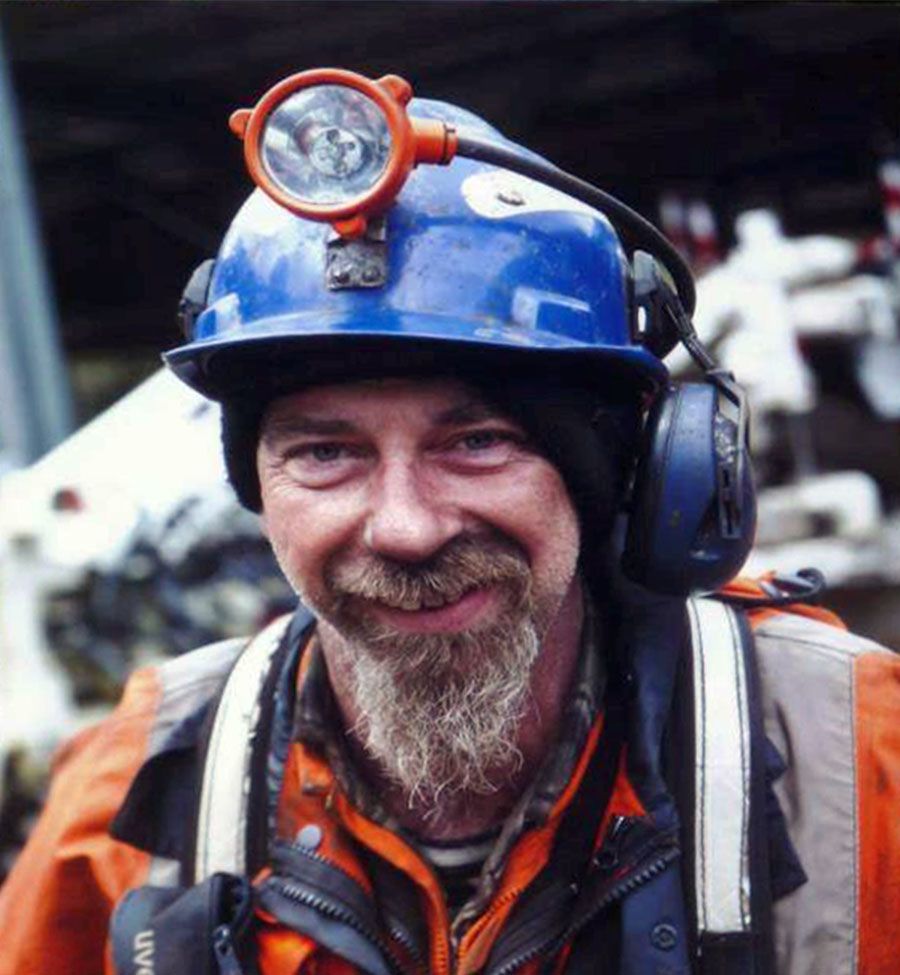

The man with the job of re-entering the Pike River mine has coal mining in the blood.

Dinghy Pattinson is a fifth generation coal-miner with personal links to West Coast mining tragedies. His great-grandfather was killed in the Brunner Mine explosion of 1896, found dead clutching a burnt bible.

His own father Dinghy (Harold) Pattinson was working at Brunner Mine in 1967 when it blew.

“I was seven, I still remember someone pulling up our driveway and saying to mum ‘the mine’s blown up’ and took off. So we waited around to see if dad was alright,” he says.

Working in a different area of the mine, his father was uninjured.

Dinghy Pattinson

Dinghy Pattinson

When Pike River exploded in November 2010, Pattinson was part of the Mines Rescue crew who spent days waiting to be allowed into the mine by police who controlled the rescue operation.

He recalls that time as “frustrating” but believes police made the right decision not to allow the crew in.

“It was a frustrating two weeks, but in saying that ... they couldn’t allow us to go in because there were no gas readings at first, we didn't know what was going on, and what you do know is, there no window of opportunity, as much as everyone says. If you’ve got a fire, you’ve got methane, you’ve got oxygen, it’s gonna explode again, it’s just a matter of when.”

Despite this, the rescue crew would have gone in if they had been told it was OK.

“ EVERY MINES RESCUE WORKER WHO WAS THERE WOULD HAVE GONE IN. THAT’S WHAT YOU DO.”

DINGHY PATTINSON

A new protocol has been introduced to the mining industry since Pike River. In the event of a mining and tunnel emergency, a mining person must be put in charge of the operation.

The whole story of Pike River and the decade since would be very different, had things been communicated better about the mens’ chances right from the first explosion, he says.

Knowing the mens’ self-rescue equipment could only keep them alive for 30 minutes, Mines Rescue was “realistic” from the start.

“My personal opinion is had they communicated better about the men’s chances, had they done that, then they should have sealed the mine. We wouldn't have got the second explosion if we’d stopped the oxygen, then we would have got back in and found out the cause, and you would have got all the bodies.

“There wouldn’t have been the four explosions, wouldn't have been the roof fall - but once someone is standing up in the public saying they are alive, they are huddled around a compressed air line, they will be wet and cold but they’re alive, who is gonna let you seal the mine – no-one.”

The mine was not sealed until November 24 when the families were finally told their men were dead.

It might have been hard for general manager Peter Whittall to be honest about the men’s survival, but it would have been better for everyone in the long-term, he says.

“Peter Whittall was a hero in the town at the time … I don’t think he would be welcome on the streets in Greymouth at the moment.”

Pattinson and geotechnical engineer Chris Lee, pictured after the first of the two airlock doors had been opened at the mine on May 21, 2019.

Pattinson and geotechnical engineer Chris Lee, pictured after the first of the two airlock doors had been opened at the mine on May 21, 2019.

Ten years on, Pattinson takes his hat off to those families for their long fight for re-entry.

“The reason I took this job is I firmly believe that 29 men should not be allowed to go to work, get killed and no-one gets held accountable. And the families have not only had no justice but they've had no closure, they don't even know what caused it (the explosion).

“We might not find out the exact cause - the Royal Commission found six possible causes - but we might be able to eliminate some of those causes and who knows, it’s probable that in the last 300 metres we are in now, we could find some human remains.

“It would be wonderful for the families, and they accept that if someone gets some remains back, that’s better than no one getting anything back.”

Acknowledging criticism of the millions spent re-entering the mine, Pattinson says the public need to think how they would feel if they had a loved one in the mine.

“To me, it’s about finding out what went wrong and trying to find evidence to hold some people accountable. It's a big thing, 29 people getting killed.

“And what we find and whatever the outcome is could prevent further tragedies, not necessarily in mining, but you could apply the same learnings to any business - bad management practices, people taking shortcuts in any business - you're going to hurt people. If we can learn from that, it's a job well done.”

Entering the Pike River drift is a fresh air recovery. The miners have been trained in forensics and are guided by police who operate from outside.

The tunnel is showing blast damage and debris. As for the mine itself, one part of the mine is flooded and underwater but the majority of the area is dry.

However, as the agency’s mandate is not to go past the rockfall that is blocking the tunnel, at this stage it is irrelevant where the bodies are and whether they are intact.

“The bodies are going to stay there unless the Government or somebody makes a decision to go further. We’ve spent $51m so far.

“Since Covid, the Government has made it clear there is no more money. Our mandate is to get to the rockfall and I'm comfortable we will get to the rockfall within our $51m.”

While Pattinson expects the drift will have been fully explored by the end of year and the whole mine sealed by the end of March 2021, the situation can change.

“We're in an area now that we've got no footage ahead of us, we don't know what’s there. If something comes up that we don’t know or don’t suspect, it could be longer.”

THE GREEN LIGHT

As the re-entry effort is in its final phase, many families will be waiting in hope of remains being found. Brenda Wilson has more cause than most to hope.

She has seen video footage of her partner John Hale, 45, at work that November day, just before the mine blew. He was the mine’s taxi driver, responsible for ferrying the workers up and down the mine’s 2.3km drift.

The footage shows him bringing 10 men out and delivering them to their changing rooms. He returns to the mine entrance for his final pick up before finishing his shift. She says she saw him sitting alone in the taxi stopped at the tunnel’s red light, unaware he was minutes from his death.

The light turns green. He drives in. Minutes later the mine explodes.

John Hale

John Hale

She wonders: how far did he get in? Is he still in the tunnel or did he make it into the mine’s workings? The tunnel is now blocked by a rockfall. Did he make it past that, could he be buried underneath it?

“I’m now thinking, are they going to come to him? I don’t want to get my hopes up though because they have been dashed in the past. He was the last one in. He will be in that drift.

“It would be good if they came across John but then, what if they get John and they didn't get the others. I need closure. I don’t want to be staying like this forever.”

Wilson lives in Dunedin where she works part-time in a cafe. She had imagined a different life.

Ten years ago, she lived in a cottage she owned near Hokitika and Hale, who lived in a neighbouring house, was helping her renovate.

Wilson has tried to put it all behind her. She has put physical distance between herself and the West Coast and the events of November 2010. But moving away has not been enough.

As a couple who lived apart, Wilson did not benefit from the money allocated to the relatives of the mine’s victims.

A creative pair who loved music and socialising, she and Hale had been friends first and slowly became a couple. Then a solo mother of three children going through a divorce, she thought she had finally found “the one”.

“I was really angry for a long time, bitter and angry, and I had to get over it. I felt robbed of our future together, I was gutted.”

After receiving counselling for her grief and anger, she realised she had to leave Hokitika.

Now she feels stuck. Unable to move forward. The Pike River mine and its morbid contents are never far from the news, or her thoughts.

3653 DAYS

The $51m cost of re-entry is one of the big ticket items in the list of costs attached to Pike River Mine.

It could easily be seen as a bottomless pit of expenditure. More than $300m was spent on the mine, said to contain $6b worth of coal, even before it failed.

Production was slow after it opened in 2008 and Pike River Coal lost about $11m in the year to June 2009 and the next year made only $3.3m at a cost of $48m.

The rescue effort supervised by the police cost about $11m and the cost of a WorkSafe and Police investigation is thought to have cost several million dollars.

The Royal Commission that reported back in 2012 saying safety measures at the mine were woefully inadequate went through a budget of about $9m.

Solid Energy bought the assets of Pike River Coal in 2012 and spent about $400,000 in maintaining the mine and preparing a re-entry plan.

The cost of the government purchasing the 3580 ha of land around the Pike River mine also needs to be factored in as does the $12m cost of developing the Paparoa Track.

Former Grey District mayor Tony Kokshoorn says Pike River was supposed to be the “jewel in the crown for the West Coast”.

Its development brought employment and downstream benefits, and helped the West Coast out of a long recession after the end of native logging in 2001.

The mine is estimated to have generated about $80m of economic benefits to the West Coast Region, about $13m of that in wages.

“ WHEN WE HAD THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS IN 2008, WE WEREN’T AFFECTED. MONEY WAS COMING IN AND THE PLACE WAS PUMPING,”

TONY KOKSHOORN

The coal price hit $300 a tonne and the mine, after early setbacks, started to look viable.

Pressure on the miners to get the coal out increased, with the company offering $10,000 bonuses and ignoring safety warnings and rising methane levels.

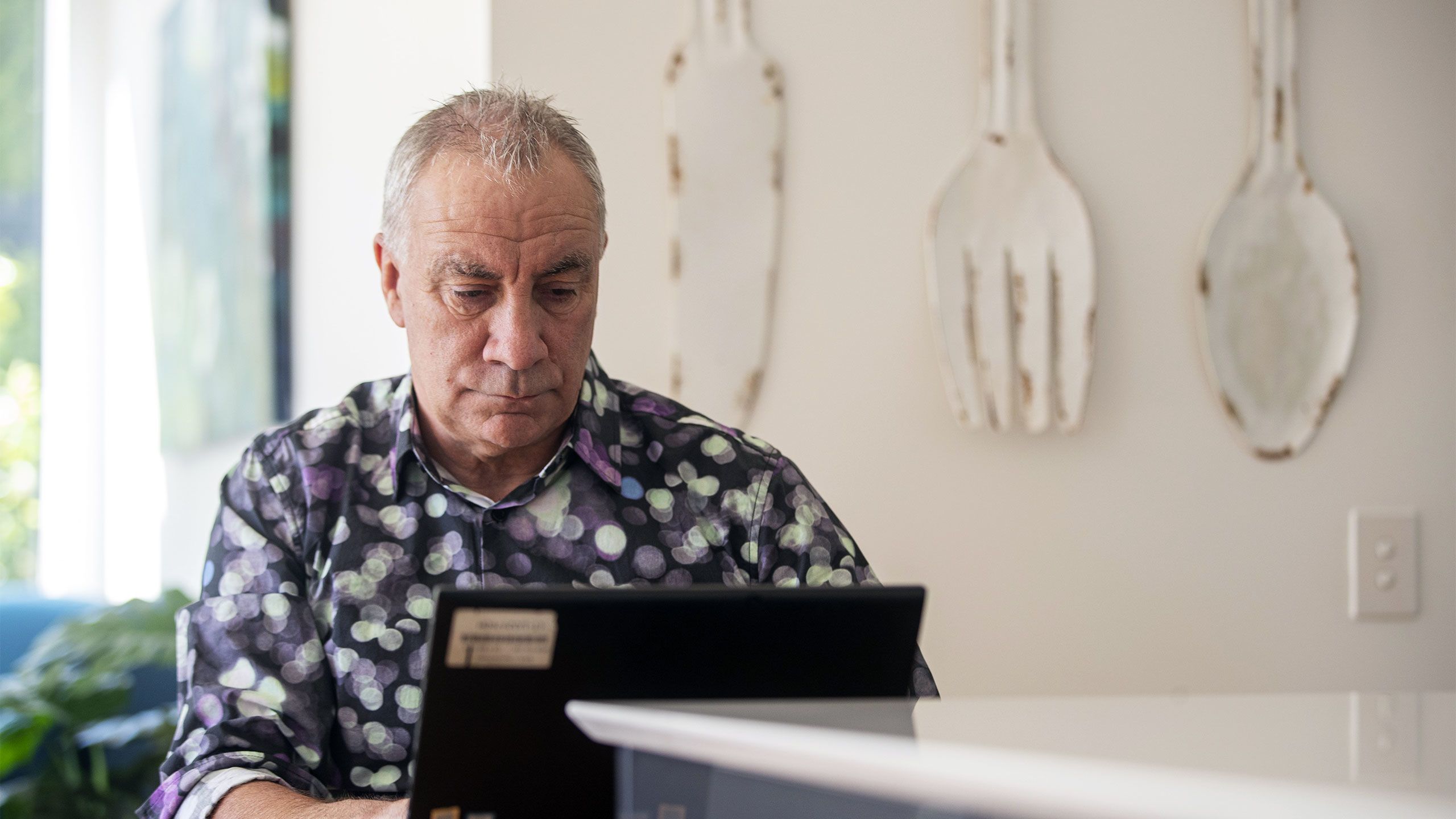

Former Grey District mayor Tony Kokshoorn reckons the struggle for re-entry to the mine took far too long to succeed.

Former Grey District mayor Tony Kokshoorn reckons the struggle for re-entry to the mine took far too long to succeed.

After the disaster, Kokshoorn set up a trust account and money began flooding in for the victims’ families.

“It was quite a nightmare at times. If you can understand the families of these miners were all different and there were marriages, defacto relationships, divorces. It became very complicated,” he says.

In the end, as he remembers it, each family got about $200,000 from the trust.

The families of the deceased and the two survivors also received about $110,000 each from a compensation package agreed between WorkSafe, Whittal and Pike River Coal Ltd.

Kokshoorn says the fight for re-entry should not have taken the families 10 long years, even if everyone had a different opinion.

“I think it did divide the community, just as it did the New Zealand public, about whether they should be going back in or not. Because it was protracted to 10 years, people did think the families should give up. But coming to the 10th anniversary now and the agency is getting to the end of the tunnel I believe $50m for re-entry is not a lot of money to do the decent thing by the families”.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern (R) is presented with a gift from Sonya Rockhouse (L) as she attends the Pike River Mine re-entry ceremony in May, 2019.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern (R) is presented with a gift from Sonya Rockhouse (L) as she attends the Pike River Mine re-entry ceremony in May, 2019.

Unless something changes, the men’s remains will stay in the mine forever.

Osborne and Rockhouse have accepted they will not be able to bring their husband and son home for much-wanted funerals and the resting place of their own choice.

Instead, they are focused on finding any evidence that could lead to a prosecution, or any human remains that may be in the tunnel.

“It’s only been a year - a year and a half - that I’ve had to accept the fact that we weren’t going to get our men back. I’d always hoped that there was going to be something that was a game changer that would make sure that the miners had to go further into the mine and get our men out,” Osborne says.

“ I’M STILL HOPING IN MY HEART OF HEARTS THAT THERE IS GOING TO BE A GAME CHANGER.”

ANNA OSBORNE

Accepting that her adored husband’s body will forever lie in the flooded mine is one of many blows Osborne has been forced to absorb in the past decade.

Her Hodgkin's lymphoma, which had been in remission twice, returned in 2018. She found tumours all through her body and was given eight to 12 months to live. Because she already had tried chemotherapy and radiation, her only option was a bone marrow transplant, a procedure that could also have killed her.

Rockhouse supported her friend through her illness and brush with death after her transplant.

“She fought bloody hard, it was awful. Three times I thought she was going to die and she wanted to, she couldn’t take much more.

“She’s not well but she’s carrying on. I won’t let her give up, if she gives up, then I'm done too. I'm not doing this without her. We started this together and I'm not doing this on my own.”

The painful transplant and recovery bought Osborne at least five more years of life - meaning she now, officially, has four years left to live. Would Milt want her to spend those years fighting for justice for his death?

“I know Milt would be very proud of what I have achieved, but I also know in my heart of hearts he’d want me to live life … I know that he would be saying ‘enough's enough, when is the end Anna, you have to live your life and carry on’.”

Osborne suffers a form of muscular dystrophy, causing her constant pain, shakes and tingles. It is eating away at her muscles and nerves and she walks with a crutch. She struggles to sleep well and cannot put on weight.

She wants more time to enjoy life with her granddaughter Amalia, who was born prematurely at 25 weeks in 2017 and spent three months in hospital.

“I feel really blessed, if I die in four years that’s OK, but I'm not going to. I've got many years ahead because that wee girl is going to keep me going.”

Anna Osborne says the fight for her husband and the other victims has given her purpose and a reason to live.

“It's not been an easy ride health-wise, but Pike has kept me alive during it because it's unfinished business. And knowing it's unfinished I don't want to go anywhere and I don't plan on going anywhere.”

In memory of the 29 men who perished at the Pike River Mine on November 19, 2010.

Conrad Adams, 43 (Greymouth)

Malcolm Campbell, 25 (Greymouth - Scottish)

Glen Cruse, 35 (Cobden)

Allan Dixon, 59 (Rununga)

Zen Drew, 21 (Greymouth)

Christopher Duggan, 31 (Greymouth)

Joseph Dunbar, 17 (Greymouth)

John Hale, 45 (Ruatapu)

Daniel Herk, 36 (Rununga)

David Hoggart, 33 (Greymouth)

Richard Holling, 41 (Blackball)

Andrew Hurren, 32 (Greymouth)

Jacobus 'Koos' Jonker, 47 (South Africa)

William Joynson, 49 (Australia)

Riki Keane, 28 (Greymouth)

Terry Kitchin, 41 (Runanga)

Samuel Mackie, 26 (Greymouth)

Francis Marden, 42 (Runanga)

Michael Monk, 23 (Greymouth)

Stuart Mudge, 31 (Rununga)

Kane Nieper, 33 (Greymouth)

Peter O'Neill, 55 (Rununga)

Milton Osborne, 54 (Ngahere)

Brendan Palmer, 27 (Cobden)

Benjamin Rockhouse, 21 (Greymouth)

Peter Rodger, 40 (Greymouth - British)

Blair Sims, 28 (Greymouth)

Joshua Ufer 25 (Australia)

Keith Valli, 62 (Winton)

Become a Stuff supporter today for as little as $1 to help our local news teams bring you reliable, independent news you can trust.

Contribute Now

Words: Amy Wright & Joanne Naish

Visuals: Chris Skelton, John Kirk-Anderson, Braden Fastier, Joseph Johnson, Iain McGregor & Getty Images

Design & layout: Aaron Wood

Editor: John Hartevelt & Martin van Beynen