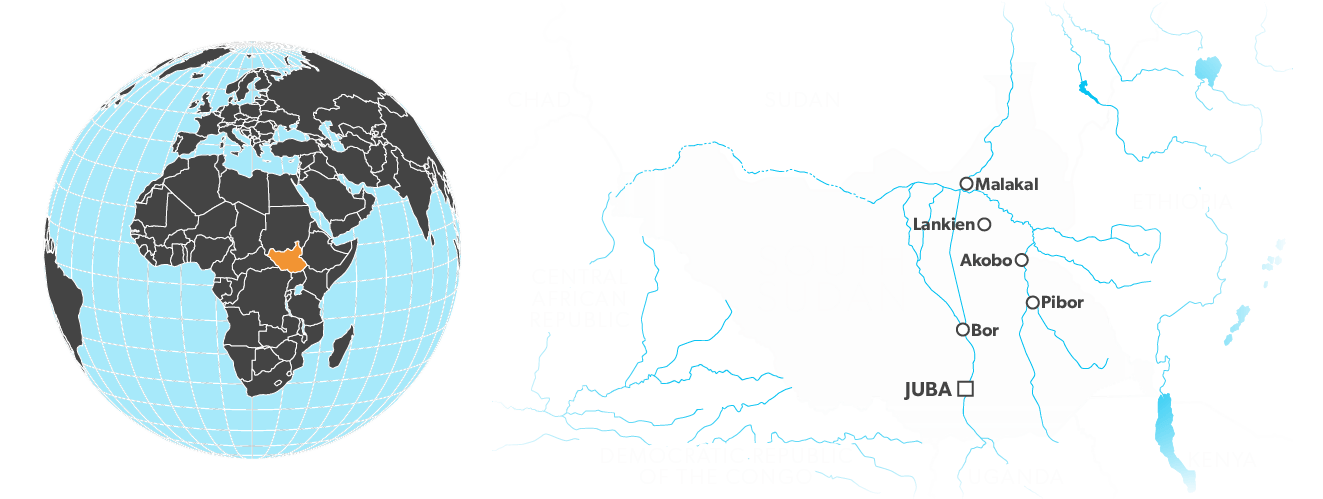

New Zealand has been sending peacekeepers to United Nations missions for 70 years, although the numbers have been scaled back in recent years. Up to four New Zealand Defence Force staff are posted to South Sudan, and military personnel are also stationed on the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, the disputed Golan Heights in south-western Syria and South Korea.

They are volatile and risky deployments - but in South Sudan, Kiwi troops are helping navigate the difficult path from war to peace, while protecting vulnerable citizens.

Andrea Vance and Iain McGregor investigate.

It rained solidly for nearly six months in Pibor, a dirt-poor town built on a flood plain. As the waters rose and rose, thousands of people gathered their things, abandoned their homes and set up camp on the highest grounds.

As the river peaked, hundreds of families crammed into a tiny area the size of a football field.

The rain finally stopped in mid-November, but Pibor’s black cotton soil is slow to absorb water, so the camp is thick with glutinous mud.

For months residents will continue to live in makeshift shelters, cobbled together from tarpaulins and children’s tents, donated from abroad.

Residents set up camp on higher ground in flood-hit Pibor.

Residents set up camp on higher ground in flood-hit Pibor.

Man-made mud walls kept back the floodwaters, but were left surrounded by puddles of stinking, stagnant green water.

The main health clinic and market were underwater, pushing food prices sky-high. Families survived on one meal a day, often river fish caught by their neighbours and displayed for sale in the baking sun, crawling with flies.

Two-thirds of water sources were contaminated and only two boreholes were usable, with long queues of women at the handmade pumps. Latrines were flooded, human excrement was visible everywhere.

The only way to move around was canoe. Children splashed and washed in the flooded brown river, but conditions were making them sick. A US Aid report in December said the prevalence of child mortality in the town was high, and 38 per cent of under-5s fell sick with suspected malaria, coughs or diarrhoea.

Children bathe and drink in a river at Pibor.

Children bathe and drink in a river at Pibor.

It was hell on earth, in a place well used to misery, sorrow and starvation.

It’s some of the worst conditions I think you’d find in South Sudan.

“It's certainly some of the worst conditions that I've seen," said Lieutenant Colonel Brent Quinn.

“All the markets are underwater, the roads are underwater and people essentially [are] living without shelter on the roads.”

Defence Force Lieutenant Colonel Brent Quinn has been stationed in South Sudan for almost a year.

Defence Force Lieutenant Colonel Brent Quinn has been stationed in South Sudan for almost a year.

The New Zealand Defence Force officer walked around the camp, assessing the humanitarian need.

It was established on the edges of the compound of David Yau Yau, Boma State governor and a former militia leader. Yau Yau said the situation was “helpless”.

“Most of the things in Boma State have been destroyed… over 78 people died. Some of the livestock, the cows in the cattle camp [were] destroyed. The belongings have been destroyed.

“The whole town… is covered with water. A lot of humanitarian [aid agencies’] private assets have been destroyed.”

Quinn’s boss, top UN official David Shearer was inside the compound, meeting Yau Yau. He would later tour the camp, and as Shearer’s military assistant Quinn was making a quick assessment.

There was no real danger - people were too weak and hungry to be a risk - but in the middle of a camp a well-maintained anti-aircraft gun was packed into the earth.

An anti-aircraft gun is positioned among tents in Pibor.

An anti-aircraft gun is positioned among tents in Pibor.

Two infants in their underwear played next to it. Another was positioned on a ute next to the dirt airfield, poorly concealed under plastic sheeting.

“There's always challenges with keeping the SRSG [special representative of the UN’s secretary general] safe,” Quinn said.

“But look, there is always allocated force protection for him and he has a close protection party.

“David travels quite a lot - it's really about getting out to those grassroots parts of the country and really understanding what's making a difference for the people of South Sudan, because that's what really counts.

And generally, everywhere we go, people receive David really well. So, we don’t feel like there is really any definitive threat to his security.

Quinn is one of four Kiwi soldiers deployed to the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS).

“When you walk around, what you'll see is everyone wearing the blue beret. Everyone is a UN peacekeeper, first and foremost. And so everything we're doing is in line with the principles and standards of the United Nations. That's what the blue beret really represents and why we all wear it.”

A soldier for 20 years, Quinn has served across the Middle East and South Pacific.

“This is my first time though to Africa. So it's a very unique experience for me.

“It's a fairly austere environment. And so it certainly is an opportunity to really challenge yourself.”

He’s been based at the UN’s main compound in Juba for just under a year, and the job involves strategic planning, organising Shearer’s multiple field trips around the country and also “making sure that what Force - the uniformed component of the mission - is doing, is aligned with the missions’ objectives".

One of those main objectives is protecting South Sudanese civilians. The signing of a peace agreement in 2018 saw 600,000 displaced people return to their homes within a year, including 20,000 from six UNMISS protection of civilian (POC) sites.

The sprawling protection of civilian site (POC) in Juba.

The sprawling protection of civilian site (POC) in Juba.

But close to 200,000 still remain sheltered by the peacekeepers, terrified by frequent inter-tribal clashes, or unsure of how to support their families.

Life in the POCs is grim.

Their ‘homes’ are makeshift and temporary - strict rules prevent residents collecting furniture other than beds and cooking equipment.

One such camp - POC3 - borders the compound where Quinn lives and works.

The peacekeepers are a familiar sight - troops from all over the world man its guard towers and enforce strict curfews. Quinn has an endearing rapport with its hundreds of children. Dozens surround him, eager to stroke the hair on his arms, a Caucasian feature they are enthralled with.

“There's obviously a lot of poverty around South Sudan, the people here live in fairly tough conditions as you see around the protection of civilian site here. [It’s] very challenging for the people of South Sudan,” he said.

But what never fails to capture me, though, is just the resilience of the people that are here. I mean, they just continue on with life, which is quite a remarkable thing when you look at what they are living in.

“The reason that we're here and the reason I think that people serve, certainly that I serve in the military, and come to places like this is because, in your own little way, you're trying to make a difference.

“This is a country where people are suffering. And any little difference that you can make gives you a real sense of self-worth and a contribution to something greater, which is the United Nations.”

The POC is divided into 10 blocks, with a main market thoroughfare. There are just shy of 30,000 residents, with 55 per cent aged under 18 and the average household holds between three and four people. Hollow-eyed men sat listlessly in plastic chairs, some playing dominoes. There were no jobs.

Life in Juba’s POC3.

The camp was cramped and filthy, but life and colour burst out of every alleyway. Music blared from speakers. The pungent stench of sewage was masked by wafts of sweet ginger coffee and turmeric from inside tin huts. Pop-up cafes advertised upcoming soccer matches, a man passed by smiling, holding two turtles under his arms and children played, everywhere.

POC3 camp chairman Joseph Matik Chuol is the community’s 46-year-old leader and works with the UN and aid agencies to help deliver emergency food, make requests and solve any problems. He has five children.

Children are born every day… they depend on aid. All the community here depends on aid. The death rate is high. Because of the situation.

“It is very hard for the children to cope with the situation. It is very hard for them, a hard life. It is not an enjoyable life. We are very worried. We are worried a lot about our safety here in the camp.”

Joseph Matik Chuol is chairman of Juba’s POC3.

Joseph Matik Chuol is chairman of Juba’s POC3.

“Even the accommodation of many people in the one place… it is very congested.

“But because of the situation [conflict] that we had in South Sudan, that's why we are here.

“It is not our wish. But what shall we do? We just bear with this situation.”

Jane Noa, 35, fled violence during the outbreak of war in 2013, running in terror across the city to the UN’s Tomping base with her eldest child, now 13.

“The soldiers they are come, they come to the home, they are getting the boys, they are killed, with the gun,” she said, in broken English.

Jane Noa has five children. “If you have children you smile,” she says.

Jane Noa has five children. “If you have children you smile,” she says.

Her husband was a civil servant, working in information technology, and she had dreams of being a lawyer. Now she lives in a mud hut with 12 other relatives. Four more children were born to her in the camp - six and three-year-old sons and year-old twins.

A lack of food means she struggles to produce enough milk to feed the babies.

“What can you do? We Africa. We like more children,” she said.

“If you have children you smile.”

If you have children you smile.

She worried about frequent bouts of violence and the effect on her children.

“In the camp, they have bad behaviours here. Because the children, they like fighting because of the war.

“Even the father don't have any work, then they don't have good food. Even the schools here, they're not good, necessarily, for children.

“The life here is not good. We are tired. You have small children. You don't have enough water. You don't have enough food.”

Jane Noa and her infant twins, born in the POC camp.

Jane Noa and her infant twins, born in the POC camp.

Conditions at the POC - and the UN base - in Malakal are much worse. A former colonial town, on the banks of the White Nile in the north, endless cycles of ethnic warfare saw it change hands a dozen times.

It was largely razed to the ground. Twisted and burnt-out cars line the roads, houses are empty, mosques looted and crop fields overgrown.

Up to 30,000 people shelter in Malakal’s POC site.

Up to 30,000 people shelter in Malakal’s POC site.

About 30,000 people shelter in the POC camp. Tensions ran high after the death of a child in an accident involving a peacekeeping truck, and it was too dangerous for Stuff to enter.

We skirted the edge of the camp, driven around by Major David McAteer, a NZDF military liaison officer stationed there.

As we passed the main POC gates, close to sunset curfew time, stones were lobbed at the vehicle. The compound’s perimeter fences were heavily guarded, with patrolmen living for long stretches in stuffy guard towers made from shipping containers.

It’s very tense at the moment just because we had a little girl die maybe three months ago, and then a kid got run over the other day, broke her arm.

“So, there were some big protests outside the Indian battalion the other day because they were the ones that were driving.

“We've had a few instances where there have been issues in the camp. Those sorts of things bubble over and they do end up coming into the camp a little bit.

“But I've never felt in danger since I've been here.”

Sunset falls over the UN base at Malakal.

McAteer plans patrols and operations, including ‘Lifeline’ which ships four weeks’ of food up the river from Juba, South Sudan’s capital.

He is also a military observer.

“We go out, we meet the local government forces, the local opposition forces as well as local community leaders.

“We head out there, talk to them about any issues they're facing, we report back to the UN. And we pass on that information so that we can get aid to the people of South Sudan.”

The White Nile is a lifeline to both UN personnel and locals.

The White Nile is a lifeline to both UN personnel and locals.

He has mixed feelings about the progress towards peace.

“Sometimes it's confusing. Sometimes, I think, that what I see in my short time here, doesn't fill me with confidence.

“Some places we are very well received, some places are really happy for the UN to be coming in.

They're very, very hospitable people. Other places, not quite as friendly. But, in my time here, it's been, it's been fairly peaceful.

Base living is very basic. McAteer lives in a tiny container - neighbouring units are pocked with bullet holes from previous battles. He gets water from a neighbouring British army camp - which is collected from the river and driven back to base. There is one canteen - which serves only chicken sandwiches, occasionally pizza and always beer.

Major David McAteer and his fellow peacekeepers have built their own shack for eating, washing and socialising.

Major David McAteer and his fellow peacekeepers have built their own shack for eating, washing and socialising.

McAteer, from Whangārei, gets most of his groceries shipped from Countdown, via NZDF headquarters, and makes sure he always has a few weeks’ surplus supplies.

“In the wet season, it rains every day. For hours a day. There's very little in the way of irrigation, of drainage,” he said.

“Both in the camp and outside. So driving is a very interesting experience.”

The roads in Malakal are unsurfaced and covered with potholes.

The roads in Malakal are unsurfaced and covered with potholes.

The weather, and incessant mud, frustrates McAteer.

“In the wet season we couldn't get out. Helicopters were cancelled because of the weather. The boats could only go sometimes because the water was too high. And we couldn't drive anywhere.

“It made it impossible to go and actually help the people. It's remarkably upsetting to live here sometimes. Some of the locations we go, they have nothing. They are living off the land. It's completely subsistence living, but they don't have much.

“The reason we're here is to help the people of South Sudan as a New Zealand Defence Force member. That's what we're doing in South Sudan.”

Malakal is South Sudan’s second-largest city but was decimated by the civil war.

Malakal is South Sudan’s second-largest city but was decimated by the civil war.

Words: Andrea Vance

Visuals: Iain McGregor

Design & layout: Aaron Wood

Editor: Warwick Rasmussen

Executive Editor: Bernadette Courtney