On Thursday, September 19, 2019, a High Court judge found that Colin Craig sexually harassed his former press secretary Rachel MacGregor for years. This interview with MacGregor was first published in September 2018.

rdinarily it would seem an exaggeration or perhaps even an elevated sense of self-importance. But when Rachel MacGregor describes the “really bad soap opera” of her life, it’s pretty hard to disagree. That soap opera has had the most public of airings, through the courts and all over the news, for four years now. But Rachel MacGregor has never had control of any of it. And she still doesn’t. As she sits down with Stuff Circuit for an interview she'd probably rather not do, she asks for time to compose herself and her answers.

rdinarily it would seem an exaggeration or perhaps even an elevated sense of self-importance. But when Rachel MacGregor describes the “really bad soap opera” of her life, it’s pretty hard to disagree. That soap opera has had the most public of airings, through the courts and all over the news, for four years now. But Rachel MacGregor has never had control of any of it. And she still doesn’t. As she sits down with Stuff Circuit for an interview she'd probably rather not do, she asks for time to compose herself and her answers.

“Because I haven’t actually talked about this in a lot of depth with anyone, really”, she says. “And I assume you’re going to ask me questions that I actually haven’t spoken about before.”

She’s nervous because she knows Colin Craig will be watching and reading every word.

If it is a soap opera, she’s right - it’s a bad one. Tawdry and crass, with enough sense of scandal for cliffhanger after cliffhanger.

But the real life version, played out in private, is one of endless stress, staggering expense, and the impacts of a monumental imbalance of power.

“Intense stress, over a long period of time”, she says. “Stress has affected just about every area of my life, actually.”

Press secretary to Craig, the then-leader of the Conservative Party, MacGregor resigned suddenly, two days before the 2014 election, and on the very same day lodged a claim of sexual harassment against Craig, with the Human Rights Commission. (Till then, the Conservative Party had been doing quite well in the polls. Did MacGregor’s resignation contribute to it falling short on election day? Maybe. It certainly was the beginning of a slow train wreck that ultimately saw Craig stand down as leader nine months later).

At mediation, MacGregor discussed the sexual harassment claim and a financial dispute - the details of which are complicated, but important.

Following her resignation, MacGregor had filed an invoice for $47,000 for work she’d done during the election campaign, from which she expected Craig to deduct two $10,000 advances, and a loan of $18,990. The interest rate on the loan was zero for the first six months, then 4 per cent for the next six months.

After she lodged the sexual harassment claim, Craig increased the interest rate to 29 per cent.

In the settlement agreement, MacGregor withdrew her claim, and over the next two days the pair’s lawyers exchanged letters which saw MacGregor paid $16,000 and have the loan wiped. At the time, it was all covered by confidentiality, meaning that should have been the end of it.

But as we all now know, it wasn’t.

Colin Craig’s first breach of the gagging order which both parties had agreed upon, came in that now notorious interview in a sauna, with TV3’s David Farrier.

Craig then went on to breach the agreement further, repeatedly, in a series of media conferences and interviews.

Rachel MacGregor sat back and watched in horror.

And it still wasn’t over.

Because then came court cases - two of them, both defamation trials - after some details of MacGregor’s time working for Craig were published by a blogger.

She was merely a witness, roped in. But she needed legal advice, of course. And now her four-year navigation of the legal system has left her with a lawyers’ bill of $80,000 - a bill which is about to be multiplied many times, because yet again, Rachel MacGregor finds herself in court: this time being sued by Colin Craig for defamation, and she responding with a counterclaim, also of defamation.

MacGregor feels she has no choice but to defend herself. But she can’t afford it.

“I don’t have any assets”, she says. “I am just absolutely nowhere near as wealthy as Colin Craig. There’s no way I could even dream of paying for this case myself. I guess it’s sort of chalk and cheese, if you like, my financial position, and my opponent’s.”

acGregor laughs frequently, but there’s a sense that she’s sussing us out; that trust doesn’t come easily anymore.

acGregor laughs frequently, but there’s a sense that she’s sussing us out; that trust doesn’t come easily anymore.

We meet in a Takapuna cafe, her favourite, partly because they let her bring her Golden Retriever, Stanley. “The centre of my world.”

A world which has changed awfully over the past four years.

And Stuff Circuit is told by several people who know MacGregor how much she has changed herself - something she frequently acknowledges.

She speaks of how tired she’s become. She makes repeated reference to the amount of weight she’s gained. She says she rarely goes out - she’s quieter, socially withdrawn - and her relationships with her friends are altered.

Partly that’s because the strict terms of the confidentiality agreement mean she can’t even talk to her friends and family about what happened.

And because of that agreement there are often lengthy pauses in conversation. She’s thinking - over-thinking - about what she’s allowed to say, because there’s so much she’s not allowed to talk about, including, of course, all the questions people want answers to: what did actually happen when she was working for Craig? What was the basis of her sexual harassment claim?

Can she answer that? No, because of that seemingly now illogical confidentiality agreement.

“I have to honour that. That’s a legal agreement that was signed on May 4th 2015 and as a result of that, all I can say about that whole time is that Colin Craig and I met and resolved our differences.”

That’s it. We’ve met and resolved our differences. No addressing the reason for her laying the complaint in the first place, no answering his denial of any sexual harassment and claim instead that there had been “inappropriate contact”. No comeback. No nothing.

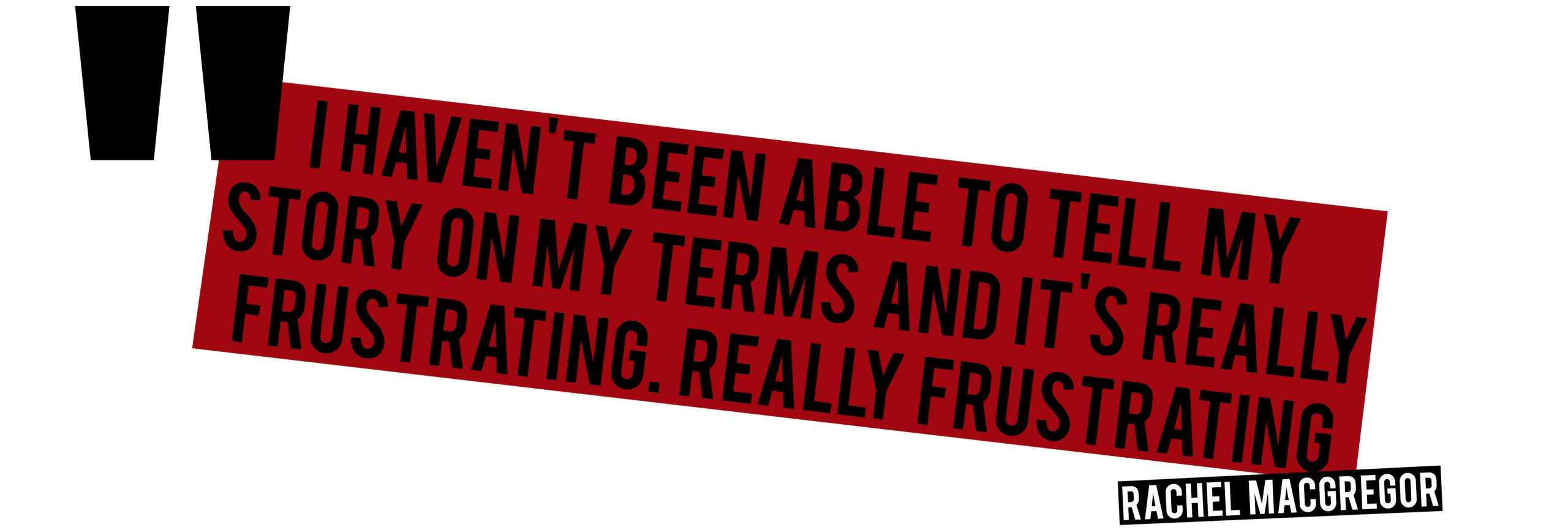

“I haven’t been able to tell my story on my terms and it’s really frustrating. Really frustrating.”

The only time she has been able to speak has been in court, but that’s brought no satisfaction, because, as a witness, “When I’ve been asked questions… they have been worded by Mr Craig or his lawyer. And so again, the narrative is very much his narrative.”

Her enforced silence has contributed to what she calls the “disaster” of her life.

Such as when she resigned from a PR job because of stress, was unable to work because of anxiety and depression, and had to apply for a sickness benefit.

With a limited income, and with Stanley in tow, it was hard to find somewhere to live.

“I had to rent this really cold and damp house and, you know, my life just completely changed.”

The role she was assigned in that bad soap opera is the character no-one would want to be.

achel MacGregor was brought up in a conservative Christian family in Auckland, her father a Presbyterian minister.

achel MacGregor was brought up in a conservative Christian family in Auckland, her father a Presbyterian minister.

It’s pretty clear she was a surprise late arrival: her parents were 63 and 43 when she was born, 12 years after the last of her three older siblings.

Which, with MacGregor now 34, makes her father 97 and her mother 77.

“They are frail”, she says, “and it’s been really difficult for them to understand, because it’s very complex, this whole process.”

A process which she says has caused them a great deal of distress.

“When I was a witness in court last time, dad went into hospital, and we were all worried that it was the stress that it had brought it on.

“Obviously like anyone, I worry about my parents. Because of their age, I just want to protect them as much as I can.”

She’s quiet when she says this.

“I mean, they just want the best for me. They don’t want me to be in this situation any more than I want to be in it.”

The impact, not just on MacGregor but on her family, is laid out in definitive language in the decision of the Human Rights Review Tribunal, to which she complained after Craig’s breaching of the terms of their confidentiality agreement.

The tribunal said, “Her elderly father has been deeply saddened by these events and Ms MacGregor feels as if she has brought shame on herself and her family.”

It went on, “Her deepest shame is that she has been identified as ‘that woman’ and will be for many years to come.”

The tribunal found Craig had caused her “severe humiliation, loss of dignity and injury to feelings”, and ordered he pay her damages of $128,000.

It was the highest sum the tribunal had awarded for emotional harm.

Rachel MacGregor is seeking no one’s pity, though, and these days, she’s finding her feet - finally. She has a new job as a public affairs manager, at a workplace where she feels valued.

“I’m really grateful to be working now, and I’ve got a really supportive workplace, who seem to appreciate me. They’re giving me leave to go to the court case.”

That case in the High Court in Auckland is set down, before a judge only, not a jury, for two weeks.

So there she’ll be again, picking her path into and out of court, seeking, probably unsuccessfully, to avoid the cameras.

The producer who in a previous life despatched cameras to film other people trying to avoid media; the hunter now the hunted.

She’ll be, no doubt, immaculately groomed, as she has been at her previous court appearances, looking every bit the television journalist she once was, gleaming in a cream suit. Clothes, it turns out, she borrowed.

It must be hell for anyone. It is hell for her.

“I never imagined in my wildest dreams - or nightmares - that I’d be the one walking into court, the one they wanted to get an image of. Trying to sneak out a back door, trying to get away.”

n June 2017, when it was revealed Colin Craig was considering suing Rachel MacGregor for defamation, journalist Alison Mau - who now works for Stuff - declared it her personal mission to make sure “Colin Craig will not be able to push his rich man’s advantage against a woman without the means to defend herself”.

n June 2017, when it was revealed Colin Craig was considering suing Rachel MacGregor for defamation, journalist Alison Mau - who now works for Stuff - declared it her personal mission to make sure “Colin Craig will not be able to push his rich man’s advantage against a woman without the means to defend herself”.

“We have crowdfunding these days”, wrote Mau, “and Colin Craig will see the women - and men - of New Zealand rise up to make sure Rachel has the money to match him head to head in court.”

A year on, a trust has been working diligently to effect just that.

Trustee Nicola Taylor, a former Russell McVeagh solicitor, now an Auckland business woman, says she and her husband Josh became involved because, “We believe all New Zealanders should have reasonable access to the mechanisms of justice, and didn’t believe Rachel would have this without some support”.

The primary role of the trust is to raise and administer funds for MacGregor’s legal defence, and so, as is the way these days when money’s needed, they’ve launched a Givealittle page. Which when you think about it is absurd: a wealthy businessman versus the hope of public generosity.

But Taylor is optimistic.

“I think most New Zealanders want to do something when they see gross inequity around them.”

Ultimately, too, Taylor wants this case to be the end of the saga for MacGregor.

“I know [Rachel] is looking to put this chapter of her life behind her and look to a future that doesn’t include Mr Craig or any further legal cases.”

For MacGregor, who frequently expresses her appreciation - and surprise - for the trust’s support, it’s still a minefield of emotion, that it’s come to this.

“It’s very humbling. It is awful to need to ask for help. It really is.”

So she too, of course, hopes she’s coming to the end of her disastrous few years.

“I’m just getting back on my feet again, and I want to be able to continue that process. I just want to live a normal life.

“I just don’t want to have to be in this awful soap opera any more.”