Ngā marae mōrearea Marae at risk

Settler law gave coastal marae a fixed location – granting Māori “little triangles” of land, as one leader puts it. Now the tide is rising, and marae can’t move.

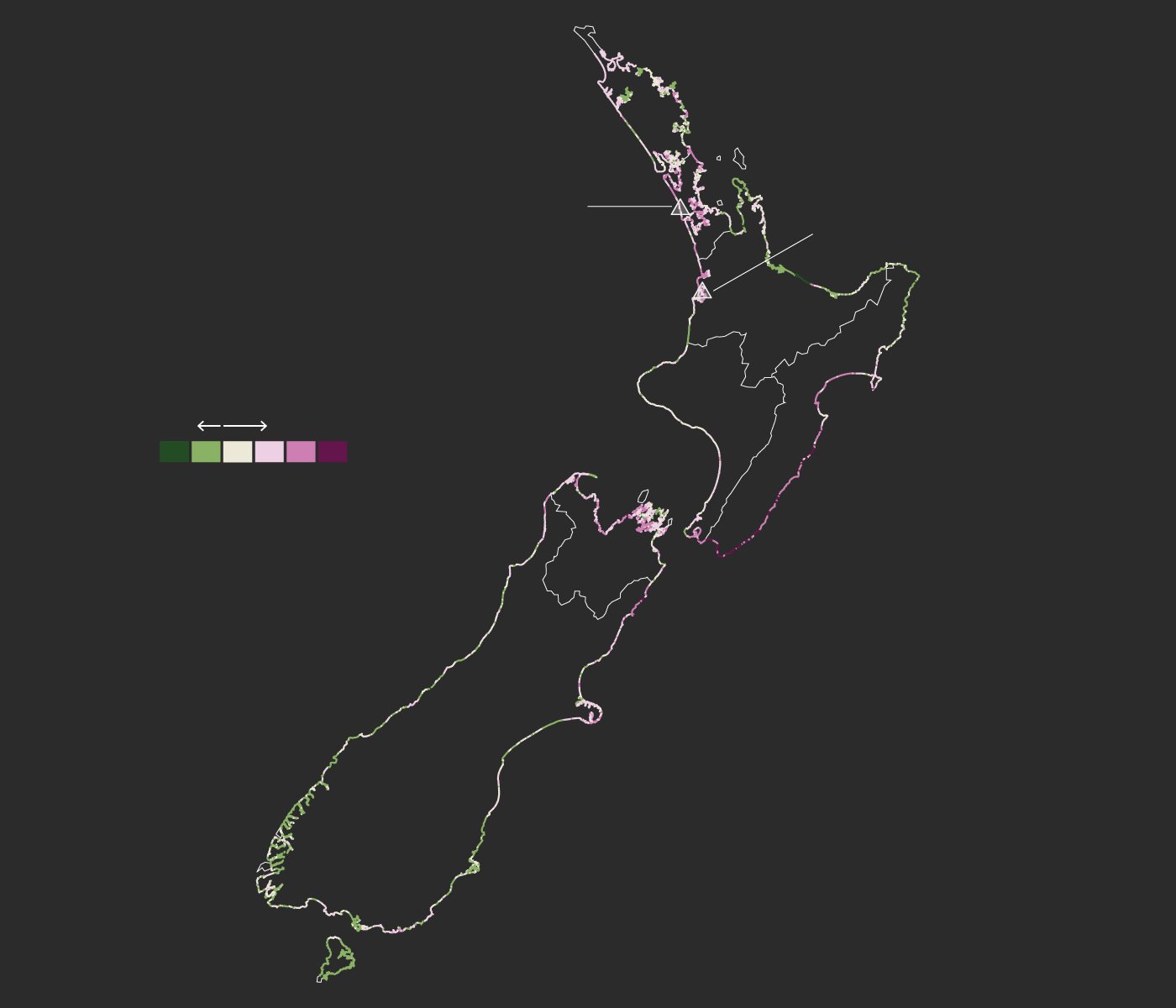

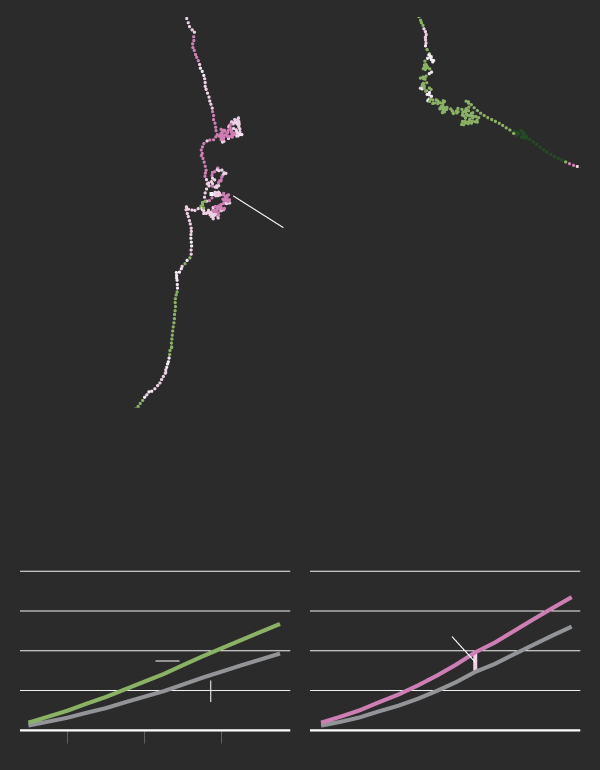

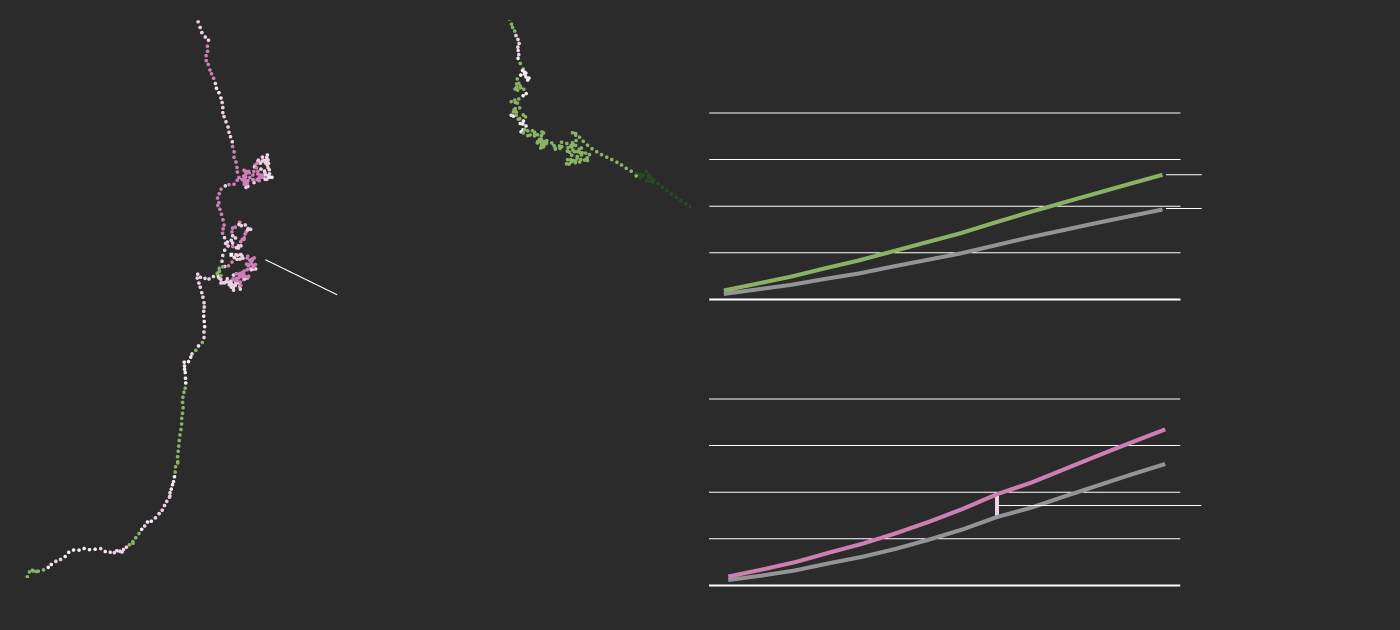

Sinking land may give Waipapa marae 25 years less to prepare for 0.5m of sea level rise

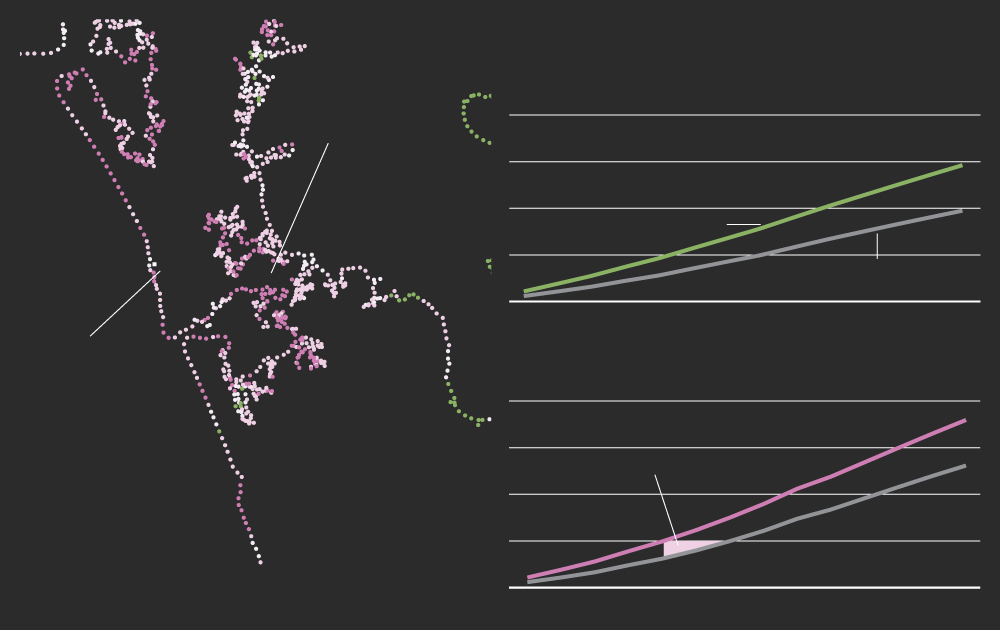

The coastline surrounding Te Henga marae could see double the effective rate of sea level rise, affecting road access

Sea level rise happens

Slower

Faster

0.5m

-0.5

0

than average by 2100 under

high emissions (SSP3-7.0)

The coastline surrounding Te Henga marae could see double the effective rate of sea level rise because of land sinking, affecting road access

Sea level rise happens

Slower

Faster

-0.5

0

0.5m

than average by 2100 under

high emissions (SSP3-7.0)

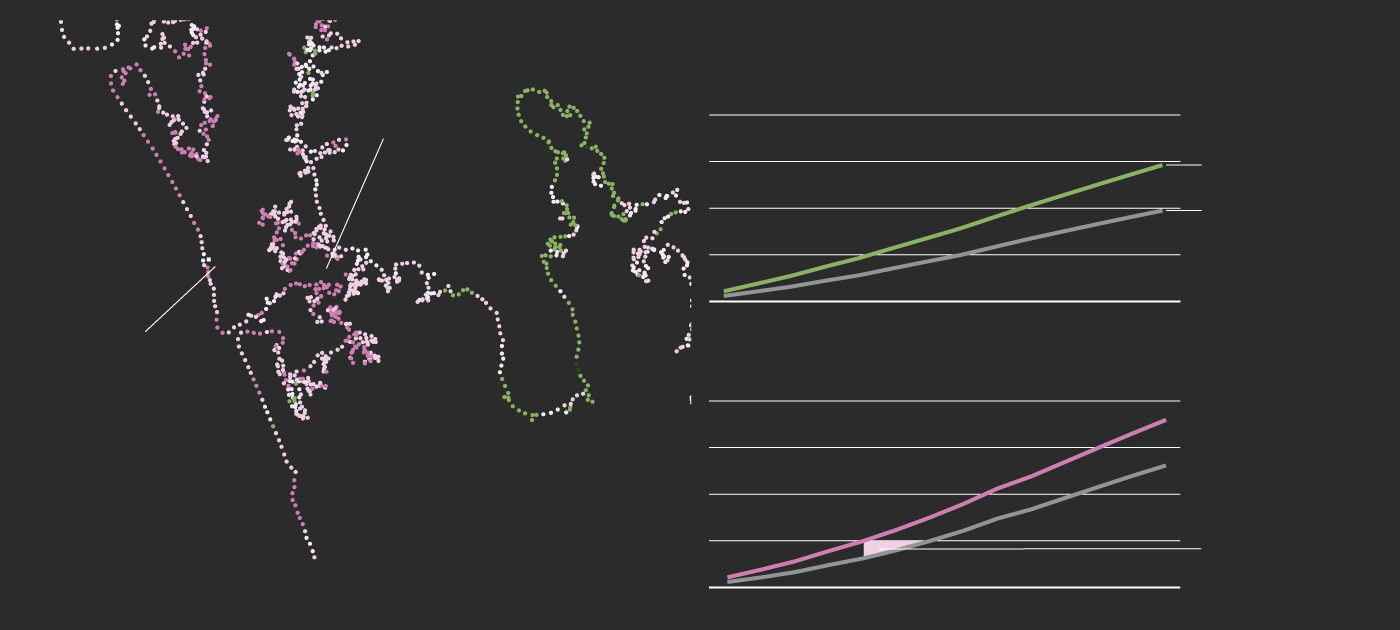

Sinking land may give people of Waipapa marae and the surrounding coastline 25 years less to prepare for 0.5m of sea level rise

Sinking land may give people of Waipapa marae and the surrounding coastline 25 years less to prepare for 0.5m of sea level rise

The coastline surrounding Te Henga marae could see double the effective rate of sea level rise because of land sinking, affecting road access

Sea level rise happens

Faster

Slower

-0.5

0

0.5m

than average by 2100 under

high emissions (SSP3-7.0)

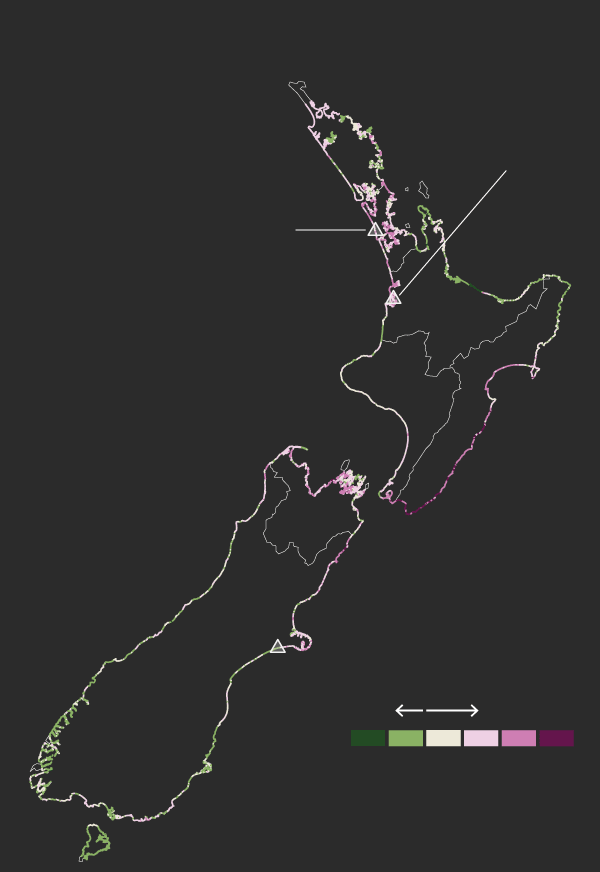

🤔 What am I looking at? The unlucky places are in pink. You might think the ocean would rise evenly around our coastline. This map shows how far from the truth that is – and how widely different the experience of sea level rise will be for different parts of the coastline and for coastal marae. Unlucky marae in parts of Auckland, Waikato, Canterbury, Northland and elsewhere could see an extra half a metre by the end of the century. Meanwhile some fortunate spots in green in the Bay of Plenty, Southland and elsewhere will experience less sea level rise than the rest of us, thanks to quirks of their geology.

Note: this map is based on high (but plausible) greenhouse gas emissions (SSP3-7.0), well above what countries are aiming for under the Paris Agreement. However, the same geographic pattern applies at lower global heating levels, even though the amounts of sea level rise are smaller.

Settler law gave coastal marae a fixed location – granting Māori “little triangles” of land, as one leader puts it. Now the tide is rising, and marae can’t move.

The empty urupā

Once, the people of Te Kawerau ā Maki held sway over everything from the cliffs of Te Henga/Bethells beach to Riverhead on the opposite harbour of what is now Auckland.

The iwi’s certificate of title (granted in the 19th Century by the Māori land court) might have covered much less land than its forebearer, Te Au o Te Whenua, had once controlled. But there was plenty of room to move with the seasons, fishing for sharks and watching as the Waitākere railway brought chainsaws to West Auckland’s kauri forests.

If that was still the case today, Te Kawerau ā Maki might be in a better position to face the ocean rising around their region.

But the Crown didn’t protect the land reserved for Te Kawerau ā Maki – and when it gave redress to the iwi, much later, it was in the form of cash and much smaller land parcels.

“Two little triangles'' is how Edward Ashby, the iwi’s environment leader, describes the pieces of land at Te Henga the iwi was given to build a new marae and urupā.

“You’re kind of left on a little island that doesn’t have much hope of sustaining you in the long term,” he says.

Not only are the two titles a fraction of the iwi’s former land area, they are coastal and (according to new research from the NZ Searise project) sited near land that is gradually sinking.

In May, Searise published the latest sea level rise projections for every 2km of New Zealand’s coastline, taking into account land movements from plate tectonics, volcanic activity, soil subsidence and more.

Based on current international emissions reduction policies, global sea levels are expected to rise about 0.6m by 2100 – or much more without emissions cuts.

An analysis by Stuff using the Searise data found seven marae located within 500m of places where the sinking land is expected to cause 20cm or more of extra sea level rise by 2100. (All those marae were also in areas previously identified by Niwa as being at risk from a severe (1-in-100 years) flood after between 0.5m and 1m of sea level rise).

The new information threatens to complicate an already difficult situation for Ashby, who is planning the new marae.

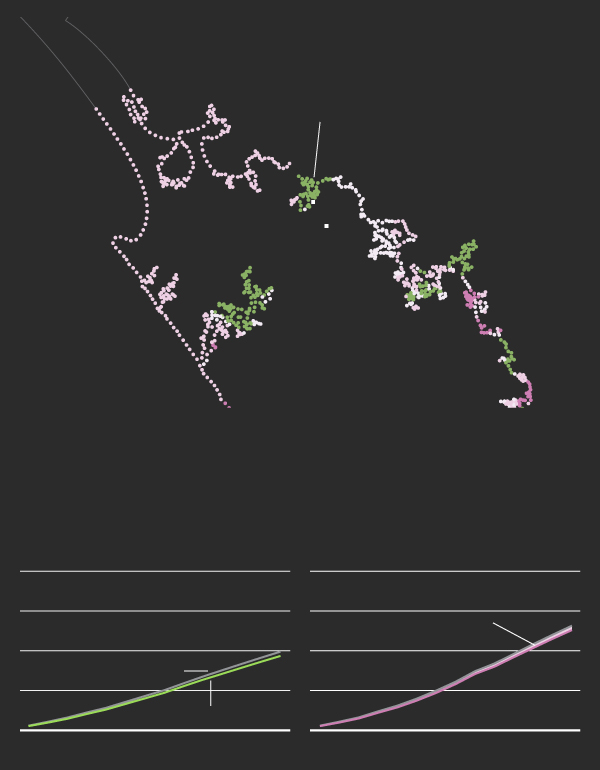

The Te Henga site is roughly 300m from a spot that is sinking at 3mm a year, which, if the marae land is similar, could approximately double the effective rate of sea level rise. That could cost the iwi and its neighbours 30 or 40 years’ of preparation time before the sea around them rises half a metre.

There’s still hope: Land movement can change over very short distances (shorter than the 2km intervals covered by the Searise data estimates). And the marae is elevated enough to stay dry for at least the rest of the century, says Ashby.

But the land meant for the urupā is a different story.

“I don’t think we’ll be burying anyone there, because they’d be under water, or at least very boggy,” says Ashby.

It’s a similar story for the only access road to the marae site. “That road will be critical,” he says. “Late last year there was a big storm that blew out the road. Folks at Bethell’s were stranded for a week.”

Te Henga, Tāmaki Makaurau

Most of Auckland

is slowly sinking

te henga

bethells beach

Sea level rise scenarios

Low emissions

High emissions

SSP2-4.5

SSP3-7.0

2m sea level rise

20 years less

to prepare

movement

no movement

2040

2080

2040

2080

2120

2120

Sea level rise scenarios

Low emissions

SSP2-4.5

Most of Auckland is slowly sinking

2m sea level rise

with movement

te henga

no movement

2080

2040

2120

Sinking land could double the effects of sea level rise

limiting road access

High emissions

SSP3-7.0

20 years less to prepare for 0.5m in 2060

2080

2040

2120

Sea level rise scenarios

Low emissions

SSP2-4.5

Most of Auckland is slowly sinking

2m sea level rise

with movement

no movement

the henga

bethells beach

2080

2040

2120

Sinking land could double the effects of sea level rise

limiting road access

SSP3-7.0

High emissions

20 years less to prepare for 0.5m

2080

2040

2120

Mobile marae

The concept of being stuck on a fixed parcel of land is relatively new to Aotearoa.

Some iwi previously had summer and winter grounds, while others moved their marae to get away from natural hazards, says Akuhata Bailey-Winiata (Ngāti Whakaue, Tūhourangi, Ngāti Tutetawha and Nāti Tāwhaki), who studies marae at risk.

“There's some research looking into the mobility of Māori, and we weren’t stationary communities. We would oftentimes move to where the resources were, we wouldn’t be stagnant and just stay in one place,” he says.

Although climate change poses a different order of risk, Bailey-Winiata hopes sharing histories of moving marae will be useful.

“Yes, the circumstances are different – we can't argue with that. [But] moving into the future, we can draw strength from those stories to understand that we can do similar things,” he says.

Today Māori land is owned in fixed titles – and those titles do not move with the tides, seasons or climate. That makes it harder to adapt, he says.

When marae have to move, Bailey-Winiata fears the Government will view compensation through a Pākehā lens.

“The people who are affiliated to that marae go back centuries, sometimes. How do we put a Western value on something which exceeds that value or sometimes has an intangible value that can’t actually be placed?”

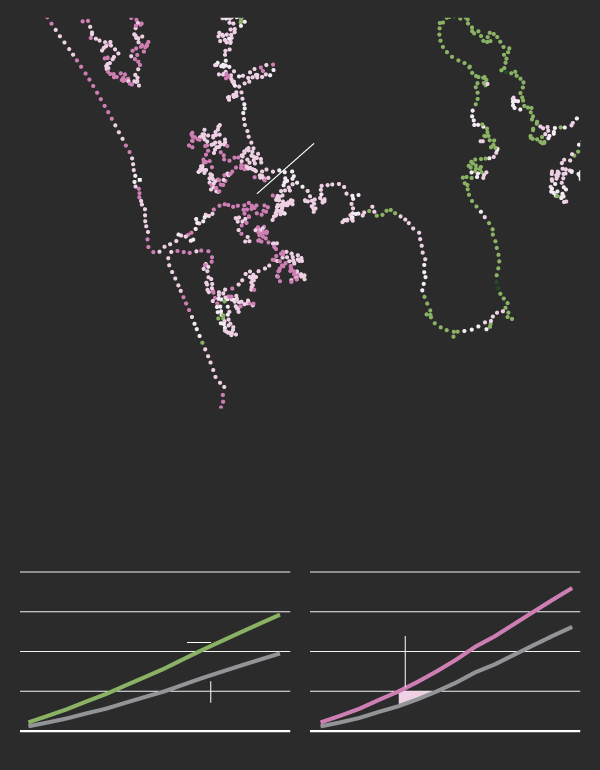

His Masters’ research at the University of Waikato found 191 marae were within a kilometre of the coastline. 41 of those marae were exposed to coastal flooding during a big, 1-in-100-year storm. For his PhD, he’s looking at what to do about it.

“Adaptation (to climate change) can actually perpetuate injustices from the past… if you have to relocate, it can reinvigorate ideas of forced relocation due to colonisation, being forced to move or forced assimilation,” Bailey-Winiata says.

“We need to be aware of the power and risk that adaptation can have in that regard.”

New urgency

South of Te Henga, on a tranquil stretch of the North Island’s otherwise wild West Coast, lie eight marae built along the Kāwhia harbour. It was the landing place of the Tainui Waka, buried on the southern end of the harbour alongside Maketū Marae.

The landing spot was a sheltered environment with water transport, fertile land, plenty of fish and kaimoana, birds and fauna for those who settled in the area. It’s not hard to see why several marae were built there.

One of these, Waipapa Marae, recently added a new wharekai. It was built to make the most of the stunning views of Kāwhia Moana and – the trustees thought – in a safe location.

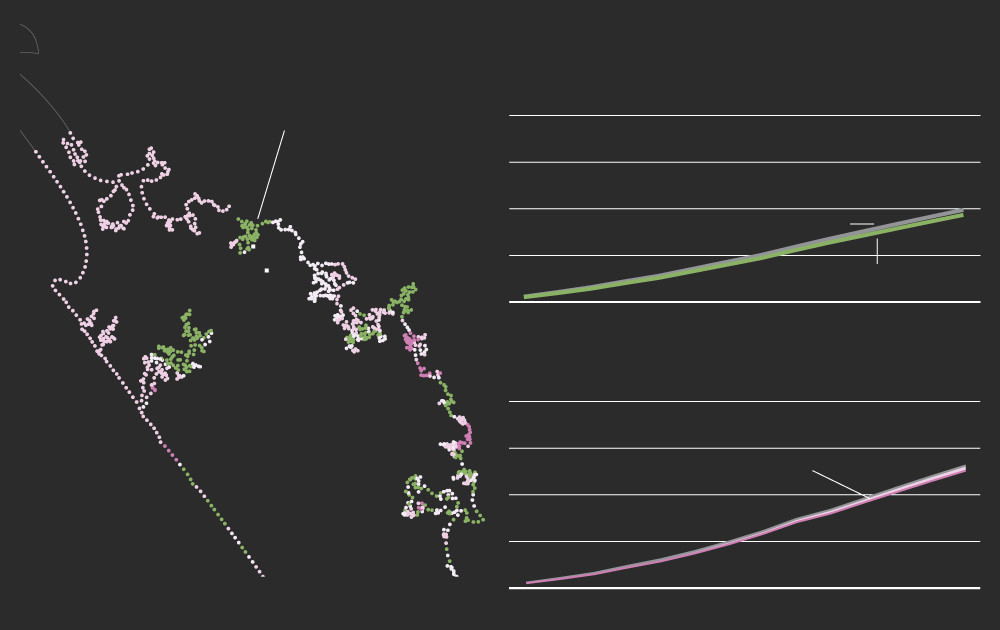

Waipapa, Waikato-Waiariki

kāwhia

Area potentially reaching 0.5m of sea level rise 25 years earlier

Sea level rise scenarios

Low emissions

High emissions

SSP2-4.5

SSP3-7.0

2m sea level rise

25 extra cm by 2100

movement

no movement

2080

2080

2040

2120

2040

2120

Sea level rise scenarios

Low emissions

SSP2-4.5

2m sea level rise

with movement

Area potentially reaching 0.5m of sea level rise 25 years earlier

kāwhia

no movement

2080

2040

2120

High emissions

SSP3-7.0

25 extra cm of sea level rise by 2100

2080

2040

2120

Sea level rise scenarios

Low emissions

SSP2-4.5

2m sea level rise

with movement

no movement

kāwhia

Area potentially reaching 0.5m of sea level rise 25 years earlier

2080

2040

2120

SSP3-7.0

High emissions

25 extra cm of sea level rise by 2100

2080

2040

2120

Yet Searise data shows land near the marae is sinking at 2.5mm a year, potentially giving people in the area 25 years less than expected to prepare for half a metre of sea level rise.

When Stuff contacts Cath Holland, the chairperson of the Waipapa Marae Trust, she takes a minute to digest the new data. She’s involved in other environmental groups and whānau land trusts in the area, and says at least six marae will be affected.

She was, she says, “probably being a bit romantic” by thinking that Waipapa was safe.

“We sit on a small hillock overlooking the harbour, but there’s a lot of wetlands down on the other side of the marae so I always thought that we were perfectly safe.

Another marae she affiliates to, further south, is already at serious risk: it will lose one of its whare into the harbour in about 10 years, she says. Whānau are discussing what to save and when to retreat from erosion and flooding.

“We’ve put in seawalls, groynes and rocks but clearly that’s not enough,” says Holland.

“When I saw the mapping, I thought instantly, Waipapa Marae is in the same situation as well. This is a really good warning for all of us.”

As with Te Henga, the Searise data isn’t a certain diagnosis of trouble – it’s a broad-level pointer, suggesting that there could be a threat worth looking into.

But her marae needs help to get the more detailed hazard mapping it needs, says Holland.

Ashby – at Te Henga – shares the same concern.

“We’re left scratching our heads because we don’t have the expertise to do a technical plan for safeguarding against sea level rise,” he says.

“It’s a bit overwhelming when you're sort of a one-person show, as many of us environment kaitiaki in hapū and marae are.”

“Funding would be great and necessary, but the Crown could also deliver some help in kind – some technical assistance and expertise,” says Ashby.

“This is a really good warning for us,” adds Holland. “We are just about to extend our urupā, and so not only is this an issue for the marae complex itself, but obviously for those of ours who are buried in an older early part of the urupā, and this new part that we’re planning to extend.”

Not too late

It is not too late to save some of these marae. But trustees need more details and support, Mike Smith, climate spokesperson for the Iwi Chairs Forum, says.

“We’re about 30 years behind where we should be. We need to be making risk assessments now for our current infrastructure – is it transportable?

“These are long conversations, and it is a major issue for governments regarding their obligations to re-settle people.”

Smith notes that flooding also comes from more extreme rain, like the storm-induced disasters that have struck the East Coast. “That could happen again this summer,” he says. “It’s not just about moving up the hill and [thinking you’ll] be OK.”

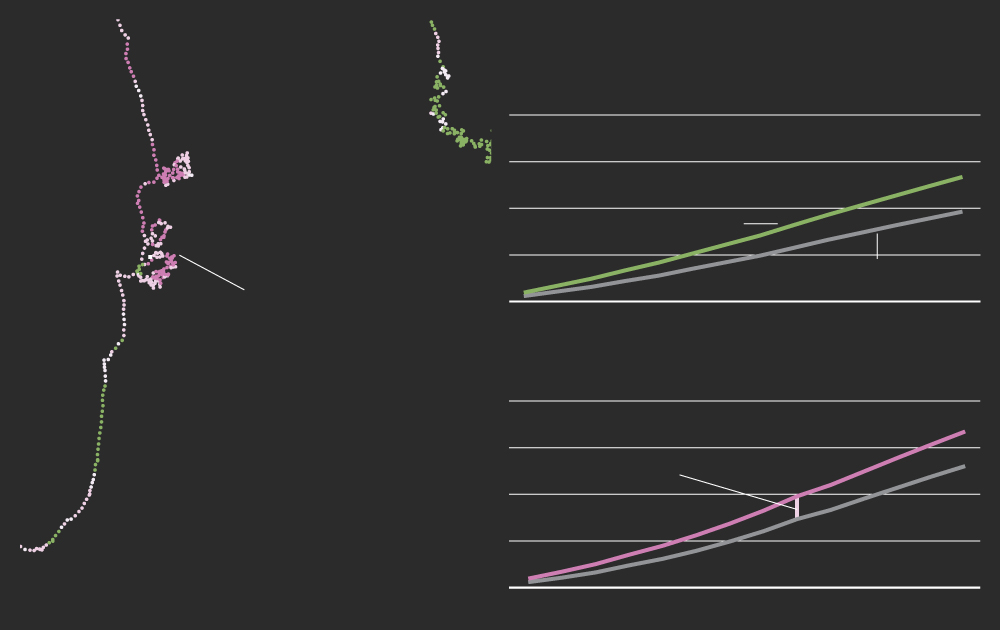

Whangaroa, Te Taitokerau

Although rising, the area is flood prone

whangaroa

kaeo

Sea level rise scenarios

Low emissions

High emissions

SSP2-4.5

SSP3-7.0

2m sea level rise

A few extra years

to prepare

no movement

movement

2080

2080

2040

2120

2040

2120

Sea level rise scenarios

Even though it is slowly rising, the land in this area is known to be flood prone

Low emissions

SSP2-4.5

2m sea level rise

no movement

whangaroa

kaeo

with movement

2080

2040

2120

SSP3-7.0

High emissions

Rising land will give the localised areas a few extra years to prepare

2080

2040

2120

Sea level rise scenarios

Even though it is slowly rising, the land in this area is known to be flood prone

Low emissions

SSP2-4.5

2m sea level rise

no movement

with movement

whangaroa

kaeo

2080

2040

2120

SSP3-7.0

High emissions

Localised areas will have a few extra years to prepare because

of rising land

2080

2040

2120

His own marae is at Whangaroa near the Bay of Islands. Fourteen marae in his local area will be affected by sea level rise or climate change, he says.

Using his rights to land at nearby Wainui Bay, Smith has launched a long-running court case against some of New Zealand’s biggest polluters, attracting support from some high profile lawyers in the process.

To him, stopping sea level rise at the root cause is the most important thing, even more important than adapting.

“Some of this is still preventable,” he says.

As the latest projections show, the difference between high and low carbon emissions could be a matter of survival for some beloved marae, as it will be for other neighbourhood gathering spots, homes and businesses.

“We can’t just move somewhere else,” says Te Henga’s Ashby. “For us, being mana whenua, it's a little more complicated.”

ℹ️ What we did: Based on current international emissions reduction policies, global sea levels are expected to rise about 0.6m by 2100. An analysis by Stuff of new public data tracking where the coast is sinking and rising found seven marae within 500m of places where the sinking land is expected to cause extra sea level rise of 20cm or more by 2100.

Not all marae located near sinking land will be at risk. To further screen marae, we overlaid the land movement data with 1-in-100 years coastal flooding data from Niwa showing areas at risk of flooding with between 0.5m and 1m of sea level rise.

Even those marae that fit within both definitions may stay dry – when we called Ōmaha Marae, north of Auckland, for example, its trustee assured us it was safe.

The locations of marae come from a public dataset from Te Puni Kokiri, which was gathered from local and central government departments, Te Kāhui Māngai, and iwi and hapū.

Stuff has not published the locations of marae unless it has spoken to a representative.

Projects like this take time and resources. Please become a Stuff supporter and help enable this type of work.

Getting to the truth takes patience and perseverance. Our reporters will spend days combing through documents, weeks cultivating delicate sources, and months – if not years – fighting through the Official Information Act, courts and red tape to deliver their stories.

By supporting Stuff you'll help our journalists keep the pressure on. Make a contribution from as little as $1 today.