Losing your hearing is frightening, frustrating and lonely. Cochlear implants can be a miracle.

But the government will only pay for 40 adults to have the surgery each year with hundreds waiting for an implant, with no real hope of relief. Surgeons say it’s a silent torture and they are tired of playing God in deciding who is most in need.

Andrea Vance and Iain McGregor investigate.

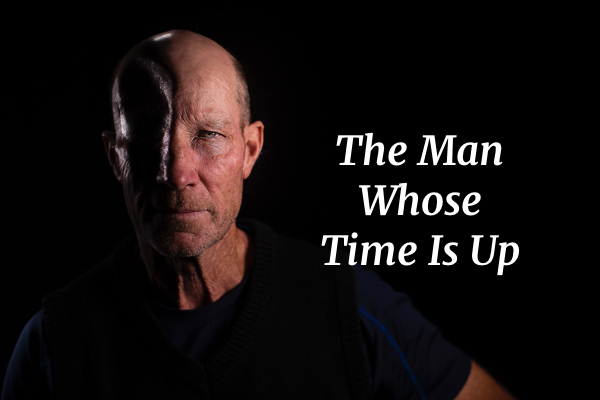

Ricky McLeod hears for the first time in more than four decades when his cochlear implant is switched on.

Ricky McLeod hears for the first time in more than four decades when his cochlear implant is switched on.

“That’s my voice. My voice,” Ricky McLeod says quietly, gently touching his left ear.

It’s been more than 40 years since he has been able to hear his own words.

Four days earlier, McLeod was fitted with a tiny electronic device, a little marvel of sound designed to help replace the hearing he lost aged 10.

With a flick of a switch on the device, he’s able to hear wind, traffic, a plane passing overhead and cicadas, the noisy sound of summer – everything we take for granted.

There are dozens of feel-good clips online showing the activation of cochlear implants, with patients breaking down and crying for joy. But, in reality, it often lacks the emotional punch as the brain tries to process the cacophony of noise it is slowly exposed to.

The first sound McLeod hears is a beep as audiologist Shirley Marshall taps lightly on her keyboard, making small adjustments to the sound processor nestled behind his ear.

A magnet inside fastens it to the implant already inside his inner ear, but McLeod moves gingerly, afraid to knock it out of place.

Marshall turns up the volume gradually. “Some people find the sound uncomfortable ... let me know if it gets too much for you,” she tells him.

“It’s bearable ... It’s awesome,” he says. She counts to 10. “It’s not clear, clear, but I can hear it.” She boosts the audio a couple of notches and recites the days of the week.

“It sort of sounds like a robot,” McLeod says and then stops as he realises he’s just heard his own voice. “My voice sounds too loud in my head. Will I get used to it? It just seems really loud,” he anxiously asks the audiologist.

Sometimes called a “bionic ear,” a cochlear implant replaces the function of the inner ear.

Sometimes called a “bionic ear,” a cochlear implant replaces the function of the inner ear.

Later, that apprehension turns to wonder as he steps out of the doors of Christchurch’s St George’s Hospital.

“I can hear something like a rattle gun,” he says, stopping in his tracks. It’s the chorus of the cicada, one of the most distinct sounds of the animal kingdom, usually imperceptible to someone just fitted with an implant.

Marshall, who also wears the device, is delighted. “Wow, that’s amazing – just amazing.

It’s strange. I can hear the wind.

McLeod tests out his new implant in Christchurch.

McLeod tests out his new implant in Christchurch.

Again, Marshall is astonished – she didn’t expect him to hear so much, so early. “Aw. Bless him,” she says.

Marshall leads McLeod out on Papanui Rd, where he stands for several moments in the bright sunshine, just listening. A bus passes, and then a woman with a pushchair.

“It’s normal,” he says, touching his ear. “It’s good. I can hear the sounds but I don’t know what they are.”

All of a sudden, his face breaks into a broad grin and points to the sky. “It’s a plane.”

“Wow,” Marshall exclaims. “Did you see it first or hear it?”

“I heard it,” he replies confidently, perfectly mimicking the low pitched whine of the engines.

McLeod lives and works in Raetihi, in the central North Island.

McLeod lives and works in Raetihi, in the central North Island.

McLeod, 52, who suffers from conductive hearing loss, has lived in silence for most of his life.

“I don’t know exactly when I went deaf, but I remember when I was about 12, 13 years old at school people started calling me an idiot and calling me names. I could read and write and I knew I wasn’t an idiot.

“I thought something else must be wrong with me. And that’s probably the first time I found out I was deaf.”

At first, he hid his impairment.

“It was embarrassing, because being young and being deaf, well, it’s not normal.

“I just wanted to be like all my other mates. Normal. So I never, ever told them.”

He retreated into a lonely world, spending most of his days in a warehouse, stripping down cars for scrap metal.

Where other mechanics listen for the “smoothness” of an engine they are fixing, McLeod places his hand on it, feeling for vibrations.

“He’s a really clever guy,” business partner Rick Horne says. “I’ve been around cars a long time and he’s taught me things.”

McLeod and his business partner Rick Horne use text messages to communicate.

McLeod and his business partner Rick Horne use text messages to communicate.

The pair have worked out a good system – when McLeod occasionally needs Horne to hear if an engine is perfectly tuned, he’ll send a text.

“Bro can’t hear or phone and I can’t spell or write, so we make a good team,” Horne jokes.

Social situations were isolating.

“Of course I’m lonely. They are all laughing and I’m sitting there like an idiot and I don’t know what they are laughing about. I do feel left out.”

“It’s alright if I’m talking to them. But once they start talking to each other I drift off. I don’t bother butting into their conversation.”

He learned to lip read, by watching television with subtitles. Hearing aids didn’t work, raising his hopes and then dashing them.

“It was too loud...It still didn’t make the sound clear, just made it a loud noise. When [my] dog barked that was hurting my ears.”

McLeod waited four years for an implant before a mystery donor stepped up.

McLeod waited four years for an implant before a mystery donor stepped up.

In 2015, McLeod was assessed for a cochlear implant and added to the waiting list. He would still be on stand-by were it not for a mystery guardian angel who stepped forward to pay for the $50,000 procedure to be done privately, after reading about his plight on Stuff.

At any one time there are 200 people in that queue – the list currently sits at 215 – and those are the ones who are lucky to be selected. They can wait five or more years.

“For every one implant that we do, we get five referrals,” says Neil Heslop, general manager of the Southern Cochlear Implant programme. It is a charity, funded by the Ministry of Health to provide public cochlear implant services to children and adults in the lower North and South Islands. It also carries out private procedures.

“People can come in over the top of people that are already on the list and they get shuffled down.

..we tell them: ‘you’re not going to be funded.’ Eighty per cent of people are being told that.

Only 40 adults will receive an implant in each year. Surgeon Phil Bird says an implant can be life-changing.

Only 40 adults will receive an implant in each year. Surgeon Phil Bird says an implant can be life-changing.

“It’s just soul destroying for the staff to communicate that message to patients. Some staff are in tears.”

Cochlear implants in New Zealand are not covered by health insurance and only 20 per cent of patients can find the money.

“People have to mortgage their house, approach family, and if they don't have that …”

Heslop says that can lead to mental health problems. “They don’t progress, they just deteriorate. Anxiety, depression, isolation.”

At $8.43 million per year, New Zealand’s national cochlear implant programme represents just 0.04 per cent of the entire health budget.

The government currently provides more than 4000 hip replacements each year at a cost of $171 million, 16,000 cataracts with a $44 million annual bill, as well as spending $199 million on knee replacements.

It pays for just 86 implants for 16 newborns, 30 children and 40 adults.

There is no waitlist for children.

Last year’s Budget brought no funding increase, although an additional 24 operations were paid for in March, with a one-off injection of $2 million.

Clinicians want an immediate boost of $6.4 million to pay for 120 adult cases each year – but that would address only the most urgent cases.

Taking the pot to $20 million would clear the waiting list.

“A waiting list is a misnomer,” says Phil Bird, the otolaryngologist who performed Ricky’s surgery. “The situation is so dire…we get referred roughly 110 people a year and we [at SCIP] have funding for 20. There is no mechanism to clear it.”

His colleagues have repeatedly criticised the disparity of access to treatment as “diabolical” and “abhorrent”.

Bird believes it is also short-sighted.

“The chances of the implant ‘not working’ is way under one per cent so it is a highly effective intervention – virtually all of our patients can benefit.

“And it’s highly cost effective. So it’s incredibly frustrating to see people that we know we can help hugely, we can change their lives, and not have the funding to do it.

“In a lot of people it’s going to help the country because they’re going to be able to pay tax because [they get] employment opportunities.“

Bird says there is also a strong, established link between hearing loss and dementia, following a study published in The Lancet medical journal in 2017.

“If they’re an older individual, it’s probably going to keep them out of a rest home longer.”

Bird implants 30-40 of the minuscule devices each year.

He makes a tiny incision, lifts up the scalp and then drills through bone to reach the inner ear, taking care not to damage the facial nerve.

He then carefully places the internal implant – roughly the size of a 50c coin – into the inner ear.

It is made up of more than 20 electrodes and a transmitting coil that curls like a fern frond.

“The cochlea itself is very slightly larger than a pea. The actual electrode, the part that goes into the cochlea, is just over 20 millimetres long,” Bird says. “So everything’s rather small.”

McLeod’s surgery takes about 90 minutes at Christchurch’s St George’s Hospital.

The cochlea – a small, spiral bony structure in the inner ear, named after the Greek word for snail – receives sound in vibrations which cause thousands of tiny hairs (stereocilia) to move.

They translate those sounds into electrical signals that are sent to the brain to be interpreted.

But the hairs can become damaged, as a result of aging, exposure to loud noise or because of a genetic condition, leading to hearing loss.

The implant bypasses the tiny hair cells and directly stimulates the auditory nerve, which sends sound signals to the brain.

“It takes a while for people to be able to turn that hearing into the ability to understand sound. Everyone’s different,” Bird says.

“Some people will say it’s a little bit like hearing a metallic Donald Duck sort of sound.

“There’s some really, really funny stories of people. I’ve heard on several occasions, people – especially women – being very embarrassed going to public toilets and hearing themselves pee.

“They haven’t heard it for decades, and become very self-aware.”

Each day McLeod and his friend perform a series of hearing tests

The first cochlear implant in New Zealand was carried out in 1986, but we now lag well behind other developed countries.

Across the ditch, in 2017 more than twice the number of Australian patients (547) received a government-funded implant than in New Zealand.

In the UK, the National Health Service has uncapped funding and if a hearing aid has no benefit over a three month period, suitable patients are entitled to an implant.

In Germany, the procedure is covered by statutory health insurance.

And in Brazil, cochlear implants are guaranteed to all ages through their national health system.

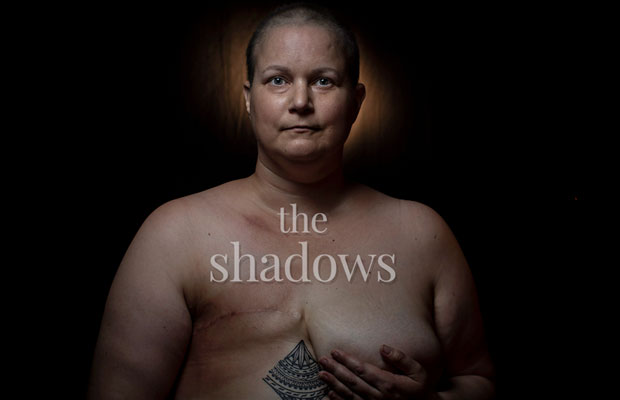

Hearing loss often sees people retreat into a “silent world”.

Hearing loss often sees people retreat into a “silent world”.

Lewis Williams, 58, says New Zealand has some of the most stringent assessment and access criteria in the world. She began losing her hearing in 1997, receding into a “silent world” before finally receiving an implant last year.

The university professor, from Tauranga, believes the Government is breaching its international obligations, under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

She has launched a petition and hopes to get it in front of MPs on Parliament’s health select committee. Currently signed by 1638 people, she’d like to boost that to 5000.

But will it help?

As chief executive of the Northern Cochlear Implant Trust (NCIT), Lee Schoushkoff has met multiple times with the Ministry of Health and ministers and was bitterly disappointed by the Government’s Wellbeing Budget.

“It just seems to us the “well-being” doesn’t apply to older adults,” he says

“These are real people who have had a quality of life that has been taken away from them and yet there is this incredible technology tantalisingly close that can enable them to get their lives back. The government has had all the cost-benefits explained to them over the years which has also been supported by international studies.

“We understand that there are competing priorities within the health budget and government cannot fully fund everything that needs support.”

These people have nowhere else to go; all avenues have been exhausted, hearing aids don’t work for them anymore ... the only hope they have for a life worth living is a cochlear implant.

NCIT, which covers patients living north of Taupo, saw a record 24 new patients in December, and Schoushkoff says the number of referrals has steadily increased in the last two years.

Ad hoc funding decisions, which see one-off boosts, put strain on the system.

“We have had a number of one-off funding injections over the years since 2005 and it is always welcomed when it happens as it does reduce the waiting list temporarily.

“However that is not an ideal long-term solution...It tends to put additional loading onto already stretched clinical staff.

“The best solution is to adequately fund 120 implants for adults per year so that the programmes have certainty and can increase the clinical capacity required to accommodate them.”

National MP Michael Woodhouse is profoundly deaf in one ear. In the future he may have to look at wearing a hearing aid.

National’s health spokesman Michael Woodhouse.

National’s health spokesman Michael Woodhouse.

“It is a very debilitating condition … I don’t think people understand quite how socially isolating.

“When I was at school, I would always sit on the right hand side of the classroom. So my good ear was out to the teacher.

“People can think I’m aloof for ignoring them. But I can function quite well and at the moment I feel like it isn’t a hindrance to my social interactions except in a large crowd, where it can be quite a problem.”

The Opposition has pledged to boost funding. During the 2017 election campaign, the National government agreed to pay for an extra 60 operations, after a campaign by 22-year-old Danielle MacKay, who spent three years on the waiting list.

Danielle MacKay fronted a campaign to increase cochlear implant funding in 2017.

Danielle MacKay fronted a campaign to increase cochlear implant funding in 2017.

The surgeries took place. But the following year, the Government discontinued the additional funding.

“It flummoxed me,” Woodhouse says.

It was callous, but it was also politically, I think, very naive.

He says National will restore the funding if elected again in September.

Associate Minister of Health Jenny Salesa says she wants to see “more significant investment” in cochlear implants and will lobby her colleagues, including Health Minister David Clark.

“It is completely inaccurate to say that National increased funding for cochlear implants, and that our Government has cut funding for this important area,” she says. “National cynically made a one-off election year spend but they didn’t lift the baseline funding to ensure their one-off hit was replicated in subsequent years.

“Disability has long been underfunded in our health system, and I acknowledge that turning around decades of underfunding will take time ... I hear from families and advocates that more is needed, including for cochlear operations.”

MacKay is now able to take on a full-time job.

MacKay is now able to take on a full-time job.

Those sentiments don’t impress MacKay, who fought hard for her implant, overcoming crippling nerves to speak to a crowd on the steps of Parliament and persuading 26,000 people to sign her petition.

She underwent the procedure in October 2017. But it has been a long and frustrating journey.

A cochlear implant is very different to a hearing aid, which simply amplify sounds. Hearing with an implant is much more active – and patients must learn to hear.

At first many just perceive noise – volume, but not speech. They often cannot understand the sound – and the brain must ‘rewire’ itself.

It can take months of hard work, speech therapy and audiology appointments before hearing becomes a reality.

“There were lots of times where I would constantly take the implant out and leave it,” she says. “The first year was the most frustrating and emotional ride ... at times I did get upset because I didn’t think it was working, and it was taking too long for my hearing to get back to normal.

“The truth is that it is still not perfect but it is a whole lot better ... Hearing the birds for the very first time, the fridge and washing machine – a weird sound to learn.

“I am now able to understand my family on the phone … it has absolutely, 100 per cent changed my life.”

MacKay chats with her co-worker Sinau Otutaha in sign language.

MacKay chats with her co-worker Sinau Otutaha in sign language.

MacKay was delighted when she landed a full time job at Turks Poultry in Foxton. “I’m fortunate enough that Turks love to have me working for them…most deaf people are stuck at home with no jobs because no-one will employ them because they can’t hear.”

She’s “sad and angry” others are being denied the same opportunities.

“Are we not important anymore? More and more people are needing a cochlear implant, and unfortunately not everyone can afford it so the waiting list just keeps getting longer.

“It’s not a luxury to us. We want a life, to be able to work for a living.”

MacKay’s campaign temporarily increased funding for 60 extra operations.

MacKay’s campaign temporarily increased funding for 60 extra operations.

At 48, Simon Baldock has given up hope of ever hearing again. He was assessed as eligible for an implant last year, but without extra funding, he will remain on the waiting list.

He says the experience is “almost cruel”.

“The impression given is that this magic wand of a cochlear implant will happen to you ... And then to receive a letter stating that you do meet the eligibility requirements comfortably [but] due to funding constraints this won’t happen. I’m still in a bit of shock processing that I won’t get one.”

A genetic condition saw his hearing begin to deteriorate as a teenager and has got progressively worse in the last 18 months.

Simon Baldock fears he will never receive an implant.

Simon Baldock fears he will never receive an implant.

A psychologist, from Picton, Baldock now fears for his job.

He says every day is “mentally and physically exhausting” and interactions with groups of people have become impossible.

“All I try to do is survive through to the end of each day as it is very tiring, physically, physiologically and emotionally.

“I used to be quite sociable, involved in football, cricket. I loved going to the theatre. Over time I have lost access to music, TV, being able to go to the cinema and conversations with more than one or two people simultaneously.

“Social gatherings I now tend to try to avoid if I can. It is really emotionally challenging to be sat there, at a family gathering, desperately wanting to be part of the conversation … but just sitting and nodding, smiling, exchanging pleasantries and not really knowing what is going on.

Do you know what it feels like to be sat at a table, surrounded by your family, wanting desperately so much to be part of the fun ... and yet feel so distant?

McLeod returns back home to Raetihi after his cochlear implant.

McLeod returns back home to Raetihi after his cochlear implant.

Almost a month after his surgery, McLeod is back at work at the garage in the small North Island town of Raetihi, adapting to life with the volume turned up.

Horne says their work days used to be punctuated by long silences, sometimes lasting two hours.

“Now he asks a lot of questions, he talks a lot more. I’ve noticed a difference.”

McLeod says he’s happier, less lonely. “I don’t feel left out anymore. I feel a lot more confident now than before … I don’t doubt myself anymore.

“Am I happier? I’ve been told I am. I feel happier too.

“I don’t have to look at a person to hear them when they talk ... I enjoy that and I enjoy hearing a phone ring, the indicators going on my car. I couldn’t hear that before.”

Sandy Brett is a close friend and travelled with McLeod to Christchurch when he underwent surgery. Each day, they carry out hearing tests together. Brett sits behind him and reads out words and sentences which Ricky repeats.

“It’s a miracle ... he’s a different person. He’s lighter. He’s more outgoing. He’s going out of his comfort zone. He’s just got a bounce to him that was never there before and he used to always be really serious ... he’d laugh but not a lot, you know, so he laughs a lot more.”

She breaks down in tears. “I would like to talk to the donor ... I want to say thank you so much for me and from McLeod because you have literally changed a man’s life for the better.

“And it’s only going to get better for him from now on.”

McLeod says he no longer feels guilt over the donation. “It works. It works for me so it must work for everyone else that needs an implant. I have still got a bit of a future ahead of me.”

WORDS Andrea Vance

VISUALS Iain McGregor

DESIGN Kathryn George

EDITOR Kathrin Goldsworthy

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bernadette Courtney