North & South writer Mike White investigates the unbelievable losses suffered by the Whatuira family - and their fight for the truth.

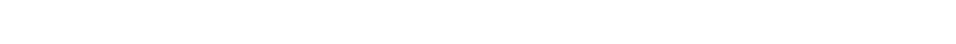

Poto Whatuira

Aged 49

Killed, Sunday January 4, 2015,

21 Ormond St, Woodville.

This is a case that probably gives rise to prejudice more than sympathy.

The shot that killed Poto Whatuira ripped into his body just behind his right armpit. It tore through his sweatshirt, scattering more than 100 pellets inside his torso - on the post-mortem X-ray they looked like a ghostly galaxy of small stars.

There was just one shot, fired from close range, knocking over Whatuira so his body lay between a log fire and armchair in the lounge of a Woodville house, surrounded by his cap and sunglasses, a broken broom, a tennis ball, and a discarded work boot. He died instantly.

Two hours after that shot, police cautiously entered the house to find it in disarray but empty, apart from Whatuira’s body and a pit bull puppy shut in a bedroom.

Everyone else who’d been there earlier had panicked, fled, sprinting to save themselves, desperate to avoid the cops and the s... storm they knew would follow the killing. The gormless, the gutless and those just caught up in something unimaginable, had all abandoned Whatuira, who lay spread-eagled across tawny carpet, the detritus of the day’s deadly events arranged chaotically around him.

Poto Whatuira was shot around 3pm on the kind of summer afternoon when kids are pleading for ice creams, and cricket is on the TV. But what led to this stretched back several hours, with some aspects still obscure.

Whatuira had left his Pahiatua home mid-morning, and driven to Woodville. With him in his silver Ford Falcon were James “Porky” Lahina, Black Power member Adam Samuels, and Christine Hickland.

Lahina’s mother had helped raise Whatuira, so the pair had known each other for years, and that day they were both wearing clothes associated with the Rebels gang, an Australian motorcycle gang that has moved into New Zealand in recent years.

Around 10am they pulled into the drive at 21 Ormond St, looking for one of its residents, Will Hartley. Hartley was away in Napier, but Whatuira and Lahina told the three other people at the house that he had been selling “chopped” drugs and owed them money. As compensation, they began taking items from the property, including guns, and loading them into their car.

There are several terms for this process, the simplest being, robbery. In gang circles it’s often called “taxing”, taking things in lieu of perceived grievances or debts, and it relies on intimidation. One of the other flatmates at Ormond St, Garry Hawker, described it as a “standover” when he texted Hartley, alerting him to what was happening.

Hartley and his mate, Danny Rei, were holidaying in the Hawke’s Bay when they got the news. Hartley quickly rang another friend, Troy “Big Block” Simmonds, in Dannevirke. Simmonds and his nephew, Scott Simmonds, picked up Dannevirke Black Power leader Michael Fiti and immediately headed to Woodville. When they arrived at Ormond St, they blocked the driveway so Whatuira and Lahina couldn’t leave, and went inside to wait for Hartley and Rei, who were speeding back from Napier. To fill in time, many of those at the house smoked methamphetamine.

At 2.15pm, Hartley marched into his house demanding, “What the f... is going on?”

Others were asked to go outside while Whatuira, Lahina, Rei and Hartley sat around the dining room table, discussing how to resolve things.

In recounting all this, it has to be understood that witnesses have told various stories, some of which conflict. Some changed their stories. Several simply refused to speak to police. Some have undoubtedly lied.

And what happened next is even murkier. But what is known is that after 45 minutes, Danny Rei got up and headed through the kitchen towards the back door. Someone at the house had by this stage stashed a loaded shotgun in the hot water cupboard beside the kitchen bench – and Rei had been told about this. So Rei flicked open the cupboard, grabbed the shotgun, and strode back into the dining room brandishing it, telling Whatuira and Lahina to “get the f... out”.

Rei claimed Whatuira and Lahina were so fried on meth, they were utterly unpredictable.

“To be perfectly clear, I could have probably pulled a unicycle out of that cupboard and rode it around the kitchen juggling bowling balls and these guys wouldn’t have seen it, they were cooked out of their minds on drugs,” he later stated. “They can’t be dealt with or quantified in lucid terms. They were insane.”

As he advanced with the shotgun, Rei claims Lahina threw a bunch of papers into the air, and Whatuira leapt up and came at him with a pistol.

“I thought he was going to kill us,” Rei said at trial. So instead, he pulled the trigger and shot Poto Whatuira, point-blank.

Porky Lahina was with Poto Whatuira on the day he died.

Porky Lahina was with Poto Whatuira on the day he died.

And then everyone ran away.

Flatmate Garry Hawker had been holed up in his bedroom but made a dash for it out the back door. As he did, Will Hartley ran into the back of him. “His eyes were like dinner plates and I guess mine were too and nothing was said, and I just bolted.”

Another flatmate, Ross Stantiall, leapt over the back fence and eventually called 111. Christine Hickland stole a car and took off back to Pahiatua. Porky Lahina, a man with “Only God Can Judge Me” tattooed across his back, ran out the front door, dumped his Rebels shirt, then collapsed on the road, eventually being taken to hospital by ambulance.

Rei claims he went to the bathroom, splashed water on his face, thinking, “What just happened? What do I do?”

Hartley, Rei and Troy Simmonds were later seen making off in Hartley’s car.

All that was left was Poto Whatuira’s body inside the house, and a bag of meth indecorously dropped on the pavement outside.

But again, this isn’t the whole story, because someone cleaned up the scene. By the time police arrived, there were no guns – not the pistol Whatuira supposedly had, not the shotgun Rei killed him with, nor any of the other guns witnesses mentioned. Mysteriously, Whatuira’s driver’s licence and cash card were discovered on a bedroom floor.

Those involved feared for their lives after the shooting. Ross Stantiall asked a mate to find him a shotgun for protection. Troy Simmonds met Poto’s nephew, Hoani Rewi, the head of Black Power in Manawatū, in an effort to apologise and clear himself of blame. Danny Rei went to his marae in Porirua, then headed back to the South Island. Will Hartley also tried to appease Poto Whatuira’s family, then went on the run, being captured by the Armed Offenders Squad and a police dog seven weeks later, wearing a wig, and hiding in bush near Hunterville.

Police charged Rei, Hartley, Scott and Troy Simmonds and Michael Fiti with murder, arguing they brought weapons to the house knowing there could be deadly consequences. But when Danny Rei took the stand at their 2016 trial, he recounted a terrifying scene of gang extortion, drugs and guns.

“They lured us in under the pretence of having a peaceable discussion and then they pulled weapons and jacked us hard out…I did not murder Poto Whatuira. I shot him in self-defence, in preservation of life, (the) life of my friend and myself.”

Because Hartley, Scott and Troy Simmonds, and Fiti declined to give evidence, it left only one other person who’d witnessed the shooting who could contest Rei’s version of events – Porky Lahina.

Lahina, 38 at the time of the trial, admitted using “the whole works” when it came to drugs, but “only the great drugs…done them all my life…no drug will ride me, I will ride the drug”. He quickly challenged suggestions they had been smoking methamphetamine for three days prior to the shooting, insisting it would have been “three weeks minimum, that’s how long we were up with no sleep.”

Claiming to be descended from Zion and Zeus, Lahina said he was “from the one-line. I’m the best at everything in the world, naturally, yes.”

But despite stating they were “New Zealand’s baddest guys”, Lahina denied Whatuira had a pistol that day.

“We were the strongest out of anyone, definitely in this country, in the world, I say. But hey, we didn’t need weapons, we always had a fair, honourable fight…The only pistol that me and the brother Poto had on every time we’ve been out together was the mouthpiece that is very strong for us, coz we know everything…I’ve been [an outlaw] all my life, I know where to play it, I know which string to pull, I know which outfit to fit, you know, it’s always custom-fitted for me, for one-liner.”

It was almost stream-of-consciousness speech, like slightly unintelligible song lyrics, and it continued for some time, as Lahina justified what they did that day and afterwards.

When defence lawyer Peter Coles asked about Poto Whatuira’s burial, when Lahina was set upon and stabbed by Black Power members for abandoning Whatuira, he revelled in the memory.

“Made me feel good, like yes, for the pain I was feeling for my lost one, yes, heal me, like, stab me, I wanted it…I’ll take that every day of my life if it was to bring my brother back.”

What the jury made of Lahina’s testimony is anyone’s guess. (Crown prosecutor Michele Wilkinson-Smith describes Lahina’s appearance in the witness box as, “terrifying.”)

But when his evidence was placed beside that of Debbie-Lee Hazelhurst, who recounted being stood-over for money by Whatuira and Lahina in 2014, and being threatened with a gun, they may have concluded it was likely Whatuira did have a pistol that day in Woodville, despite one never being found.

Whatever they thought, they concluded Danny Rei had acted in self-defence when he shot Poto Whatuira - and pronounced all five defendants not guilty.

When the jury foreman announced Rei not guilty of murder or manslaughter, “all hell broke loose”, remembers Will Hartley’s lawyer, Peter Coles.

Incensed at the verdicts, Whatuira’s family shouted and tried to get to the defendants, who stood in the dock behind glass screens. “There were serious threats made, there was yelling and screaming, as well as general accusations about a lack of justice in the system,” remembers Coles. “It was just such an uproar.”

Lawyers and court staff were ushered into the courthouse’s library for their safety, where they stayed for several hours, while police called in reinforcements and tried to quell the melee outside.

Meanwhile, the five acquitted defendants wanted to be released immediately, but to avoid a confrontation with the Whatuira family, they were let out a side door into an alleyway.

“Unfortunately that turned out not to be ideal, given that as they came out, a very angry group of people were at the end of the alleyway,” says Coles. “And the only thing between that very angry group and the defendants, were a very limited number of police officers who did a hell of a good job keeping them apart.”

Will Hartley wasn’t in any hurry though. Taking his first steps of freedom for months, he casually lit a cigarette, then challenged the Whatuira family, Coles recalls. “He was dancing on the balls of his feet, gesturing with both hands.” Eventually he and the other defendants were bundled into police cars and driven away, past the Whatuira family. Past a family again left with a sense of no justice, and no home for their anger.

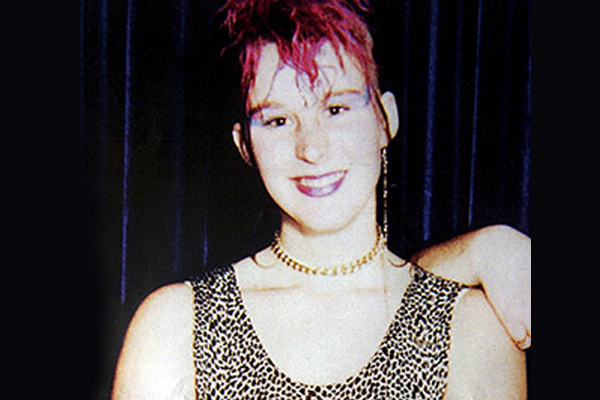

Tama Whatuira, son of Poto Whatuira, with photo of his father.

Tama Whatuira, son of Poto Whatuira, with photo of his father.

Tama Whatuira, Poto’s son, sits in the lounge of his Palmerston North home and recalls the outburst in the courtroom as Danny Rei and the others were found not guilty.

“My family kind of erupted with emotions. Everyone was crying and screaming. They couldn’t believe it, it was surreal. I thought at least Danny Rei was going to get manslaughter.” But Rei – and the Whatuira family – got nothing.

Tama says during the trial, some of the defendants were giving the family the fingers behind their backs, and Rei’s tearful testimony in court was purely an act for the jury.

“He’s a bulls... artist. He’s looking at years in jail, so of course he’s going to get up and cry and do whatever it takes to get off. And afterwards, they were laughing at us, in the family’s face, and clapping. That was just the rudest slap in the face, I just couldn’t believe it.”

For Tama, one of his greatest grievances in the whole trial process was the way every bad thing about his father could be brought out, and Poto was painted as a tattooed gangster who got what he deserved, while nobody knew about the other side of Danny Rei, or Will Hartley or the others.

How they knew nothing of Rei’s criminal past and Nomad gang connections. Or how he was on a charge of threatening to kill and castrate a prison officer while on remand for Poto’s murder – for which he was later sentenced to jail.

How they didn’t know about Hartley’s 37 previous convictions and numerous stints in prison. Or how in 2011 Hartley barricaded himself in a house and pointed a loaded and cocked rifle at police trying to arrest him, and was eventually shot twice by an officer to disarm him.

How they never knew about Michael Fiti’s five previous firearms charges, including possession of a Sig Sauer pistol stolen from Linton Military Camp.

None of this was allowed to be heard by the jury, because it was considered prejudicial – but Poto Whatuira’s life was fair game, it seemed, to be made one-dimensional and denigrated.

So here are some other things the jury didn’t hear – about Poto Whatuira, this time.

How he was born in New Plymouth, grew up in Manawatū, and didn’t discover who his birth father was until his 30s, by which time his father was dead. How his first name was James, but he was known by his middle name, Poto, meaning “little” or “short”. How his mother died when he was about 14, in his first year of college, and he was largely left to look after himself, going from place to place, sleeping in woolsheds, doing burglaries to get by, and ending up in Levin’s Kohitere boys’ home.

How he could turn his hand to anything, building, engineering, mechanics, and spent his life doing up and selling cars. How he’d been a bouncer and worked at the Takapau freezing works, worked out in the gym and kept in shape. How he bought five acres near Pahiatua, converted an old woolshed into a home, and planted 2000 native trees and bushes. How he did most of the cooking when Tama was growing up. How, when his partner of 20 years left, Poto quit his job to look after their six children, including a toddler still in nappies. How he never missed a match when his boys started playing rugby and league and basketball; how he drove the van picking up all the other kids for training when Tama and brother Hemi made Manawatū rep teams; and how, when they were older and playing senior rugby, he’d shout jugs for the players at the pub after the game.

How he’d be the first to put up his hand to help on school camps.

“He was that parent,” says Tama. “Just one of those proud as punch fathers, always your biggest supporter.”

And how he was very anti-gangs, despite being surrounded by them, despite his brother John being the head of Black Power in Manawatū, and another brother being a Nomad. So much so that, when they were living in Palmerston North’s gang heartland of Highbury and violence erupted after Wallace Whatuira’s murder, Poto shifted the family to Pahiatua, Tama says.

“He didn’t want any of that for us. Our cousins were all running around, prospects, under Uncle John, wanting to be him, wanting to be gangsters, wearing the blue rags and all that. And I was just coming to an age where I could have been quite easily influenced to follow and go down the wrong path. You are what you hang out with.”

When Poto’s oldest son, Poto Jr, joined Black Power, Poto refused to give him a 21st birthday celebration, telling him if he thought Black Power was now his family, they could put on his party.

Nobody was ever allowed in Poto’s house wearing a gang patch.

Tama can’t explain why his father seems to have hooked up with the Rebels in his last days, after a lifetime staying apart from gangs. A few months before his death, someone fired a shot through the window of Poto’s house. A week later, he turned up with Rebels gear, and his sister, Koia, thinks Poto felt joining the gang could help protect his family.

Still, Tama can’t understand why Poto was at that Woodville house, involved in a standover, when he got shot, other than being there to support Lahina.

I always knew Porky was bad news, as soon as he came into the picture, like the devil on Dad’s shoulder. All these ideas of his – bad ideas.

Despite Danny Rei’s claims Poto had a pistol, which were partly supported by Debbie-Lee Hazelhurst’s evidence from events in 2014, Tama still doesn’t believe his father had a gun when shot. He never saw his father with a gun, and says nobody, other than Rei, gave evidence Poto was armed, and no pistol was ever found.

“If he did have one, where is it? Why would Danny Rei get rid of it, when it’s the one thing that could justify him doing what he did?”

Tama also says the shot from Rei hit Poto behind his right armpit, as if Poto was holding up his arm defensively. If Poto had been advancing and pointing a pistol at Rei, this part of his body wouldn’t have been exposed.

“Why would a man, who supposedly had a gun, shield himself? That’s what I don’t get. That’s why I can’t believe the jury couldn’t see that. And even if there was a doubt, why wasn’t it manslaughter? He still pulled the trigger and killed a man. The gun (that Poto supposedly had) never existed.”

What’s more, Tama wonders how the jury didn’t deem the shooting premeditated. There were texts instructing Poto and Porky be kept at the house until Rei and Hartley arrived. And how could a loaded shotgun be deliberately placed in the hot water cupboard and Rei told about it, if there was no intention to use it?

Moreover, even Rei admits he walked into the dining room pointing the loaded shotgun at Poto and Porky Lahina. This shows Rei was the actual aggressor, Tama says, and anything his father did was in self-defence – not the other way around, as portrayed in court.

“At the end of the day an unarmed man got shot. And [the defendants] did everything they could in court to cover their own arse.”

Poto Whatuira's grave in Pahiatua

Poto Whatuira's grave in Pahiatua

Courtroom claims Poto had been on a weeks-long P bender before his death, simply don’t ring true for Tama, either. (Toxicology tests couldn’t say how much methamphetamine Poto had consumed.)

He’d been with his Dad on Christmas Day at the family homestead in Pahiatua. “Pork roast, ham – even though he was a single dad he still cooked a massive spread.” He saw Poto again on New Year’s Day when Tama had a barbecue at his house. And on January 3, Poto again dropped round for a coffee, and seemed completely normal.

The following day, Tama and his brother Hemi had just got home from the gym when their aunt phoned saying Poto had been shot. By the time they arrived in Woodville, armed officers barred them from entering the house, but after two hours, a detective confirmed their father was dead.

“And from that point, I never left him,” says Tama.

He and Hemi performed a haka as their father’s body was removed the next day; followed him to the hospital; identified him; put a mattress in a ute, bought some flowers and took him to the funeral home; bought a suit to dress him in; and led a hikoi of 30 cars for “one last ride through the hood” of Highbury where they used to live, before bringing him home to Pahiatua. From there, they took Poto to his marae in Masterton, where hundreds of mourners gathered, before a final journey to the Pahiatua cemetery where Poto’s mother and brother were buried, as well as his nephew Wallace.

But as they were filling the grave, Tama heard screaming from the distance where Black Power prospects had set on Porky Lahina for abandoning Poto the day he was shot.

“So I had to drop the shovel, and me and Hemi went flying over and ripped them off – some of them were my cousins. Like, we were laying my Dad to rest and it’s been a good day and now the biggest memory everyone’s going to take away from it is how Black Power got their boys to stab Porky, while they’re still in the cemetery. I don’t need trouble. All these guys are trouble.”

Tama knows he had a lucky escape from gang life when Poto shifted the family to Pahiatua from Highbury, where he’d seen “heaps of s..., growing up”.

Instead, Tama left school and got a job at the freezing works, then got his digger and truck licences and went drainlaying in Wellington. When he met his partner, Ashaya, they moved back to Palmerston North and Tama took a job with the Manawatū District Council. At 27, he now supervises the region’s wastewater treatment plants, and oversees five staff. He and Ashaya bought their house four years ago and have three children. Despite the image of Poto that arose during the trial, Tama insists his Dad was a good role model. He taught him to work hard, pay your bills, respect your parents, always help those in need - the things Tama hopes to pass on to his younger siblings and children.

“In my family, I’ve got a lot of mischief. But if you look at all the six kids Dad raised directly, none of them have ever had any interest in being in a gang.”

Plenty of Tama’s mates and relations did end up in Black Power or the Mongrel Mob.

“It’s just the way you grow up and the way your paths go.”

And while the path to a gang patch is one he’s determined his children and younger brothers won’t take, Tama admits in the wake of his father’s death, this conviction wavered and thoughts of revenge fleetingly surfaced.

"They were there – it’d be so easy to just go join Black Power. But I had a daughter then, and my partner, and everything we’d worked for, and I knew Dad would be looking down on me going, ‘Don’t be stupid son, don’t throw away everything you’ve got and you’ve achieved, for me. What’s done is done. You just be the best man you can be.’ I know that’s what would make him more proud. So that’s what I decided to do.”

Tama Whatuira says his dad was a good role model - he taught him to work hard, pay the bills and always help those in need.

Tama Whatuira says his dad was a good role model - he taught him to work hard, pay the bills and always help those in need.

Despite everything that happened, Tama Whatuira doesn’t blame police for the fact the five men accused of killing his father walked free. But he’s not as equable about the defence lawyers who helped them.

“I know it’s their job, but with the evidence that came forward, you think, how do you sleep at night? Some part of you has to tell you that this man you’re defending didn’t do this in self-defence.”

Danny Rei’s lawyer, Christopher Stevenson, understands the Whatuira family feeling aggrieved at the jury’s verdicts and nobody being held responsible for killing Poto.

“But what the law says is, if you find yourself in circumstances where you need to defend yourself and/or others, and you use force such is reasonable in the circumstances as you believe them to be at the time, then the action you take is justifiable.

“Our position always was that there was a response to a situation [Rei and Hartley] encountered – it’s very, very sad at the end of the day that somebody died.”

(Rei couldn’t be contacted for comment. Stevenson said he’d also been unable to contact Rei.)

Peter Coles, who defended Will Hartley, says the jury’s verdicts were “entirely correct” given the evidence, the law, and the judge’s directions to them.

The person who is responsible for Poto Whatuira’s death was Poto Whatuira.

“That may sound unduly harsh, but if you put on gang regalia, and go into someone’s house to steal their property, and things go beyond your control, you really can’t say that it’s unfair. But it’s a totally different situation for his family, I appreciate that.

“The overriding factor in this case, for me, was the methamphetamine issue. It is without doubt the most far-reaching, insidious, pernicious and dangerous drug I’ve seen in the community in the 44 years I was a practising defence lawyer. It’s wreaking massive havoc. And guns: guns were designed for one purpose. They aren’t designed to frighten, they aren’t designed to wound or maim, the primary purpose of a firearm is to kill what it’s pointed at – be it a duck or deer or person. And if you put guns and methamphetamine together, that’s beyond volatile. And if you introduce gang culture, where people think because they’re wearing a piece of cloth, or insignia, they are somehow bulletproof, then it’s just a recipe for total disaster.”

Michele Wilkinson-Smith, the Crown prosecutor at the trial, says several things may have undermined getting a conviction. Poto Whatuira wasn’t portrayed as an entirely likable or innocent victim. And the only witness other than Rei who described what happened was Porky Lahina, someone with serious drug-use and psychosis problems, making it more difficult for jurors to rely on his evidence.

The inability to counter Poto’s character failings with Rei’s criminal or gang background, also hampered Crown attempts to add balance.

But ultimately, Wilkinson-Smith says, on the evidence presented it wasn’t unreasonable for the jury to decide Rei acted legitimately.

“It’s got to be beyond reasonable doubt to get a conviction. That’s the system. That’s the system for everyone. And the evidence simply wasn’t good enough to exclude self-defence.”

Tama Whatuira has sometimes hoped he might meet Danny Rei in the street, and reckons he could have easily dealt with Rei in a fight, taken him down. When you feel there’s been no justice through official channels, such thoughts inevitably rise.

No matter what the lawyers say, no matter what the jury decided, nothing will shake Tama’s view that his father was murdered. He misses him so terribly.

Six months after his father was killed, Tama organised a party to mark what would have been Poto’s 50th birthday. They put down a hangi, got a cake with a red mustang on it (one of Poto’s favourite cars), and visited his grave in Pahiatua. They go there often. Every birthday and Christmas Day without fail. The rest of the family usually turn up. The kids ride their bikes around, the adults toast and remember Poto.

They remember how Poto would just randomly turn up, always bringing something, fish, a meat pack, a feed of paua. How when Tama’s first child was born, Poto arrived with champagne, whisky and cigars. How he gave Ashaya a gold ring with the child's name engraved on it, to mark the event. How he organised a pig on a spit and a bouncy castle for the child's first birthday. How he arrived with a big bag of dresses and a teddy bear on her second birthday, three weeks before he was shot. How she has jewellery Poto gave her that she will wear when she grows up. How he’d be so proud of all her certificates from school that cover the fridge at Tama’s home. How nobody outside their family knows anything of this. And how he hates how his father is now publicly defined by what happened in that Woodville house, that was later gutted in an arson attack.

“Because he touched the hearts of a lot of people. If he loved you, if you were in his circle, he’d do anything for you.”

Tama sometimes thinks he’ll get a tattoo of his father, behind his right shoulder, where the shotgun blast hit Poto. He doesn’t need it to remind him of his Dad, but it would point to the injustice he feels they’ve suffered.

He can’t get his father back, all he can do is make the most of his life and make sure his kids, Poto’s grandkids, are safe and loved and achieve great things. That will be the best answer for all those who have vilified Poto and stereotype the family.

“Just got to keep leaning forward - your feet will follow.”

Read part 3

Words: Mike White

Design & layout: Aaron Wood

Interactive design: John Harford