The drinking buddies who bamboozled police with their close-to-perfect bank job.

As detectives set about looking for an international crime syndicate, two local lads were crumpling their crisp new bank notes to avoid suspicion. More than 50 years on, Chloe Ranford discovers some of the money was never recovered.

Great stories don't have a use by date. So here’s a fantastic listen from the Stuff archives. Hear one of our excellent pieces of journalism told on The Long Read on your favourite podcast platform or in the player below - or have a read.

The Long Read is proudly brought to you by Auckland Museum

"Are you ready?"

"Ready? Ready for what?"

"The heist."

Ray Hancock had just been woken by his long-time drinking buddy and friend, Geoff Sergent.

The perfect bank job was something the pair had talked about in the pub with mates. They loved to plot ways to break the shackles of boredom and low pay in 1960s small town New Zealand.

But here, in the middle of an April night in 1968, was the dare to make it real.

With Sergent standing over him, Hancock was being asked to put his money where his mouth was.

"Make me a cup of coffee while I get dressed," Hancock replied.

BLENHEIM WAS ‘BORING’

Hancock was a strongly built man with blond, curly hair.

In March 1968, aged 29, he was an engineer at Simonsen's Brothers, a commercial piggery just outside Blenheim. He'd been working there for two years. He had nothing but a parking ticket to his name.

The Simonsen's Brothers commercial piggery, in Riverlands. Pictured in the 1970s.

The Simonsen's Brothers commercial piggery, in Riverlands. Pictured in the 1970s.

He liked a drink at the end of the week with his mates, including the then 23-year-old Sergent. They'd been friends for more than five years.

Blenheim pubs were given permission to serve drinks until 10pm just five months earlier, after closing at 6pm for 50 years. After a few late-night drinks, the friends would often delve into a discussion about money.

Marlborough was a low-income area, and most folks were strapped for cash. Unemployment was a part of life. An average three-bedroom house cost $8280 (now about $142,000), having risen 24.2 per cent in eight years.

Hancock recalled the 1960s being "dead boring for everyone around", as "nothing was happening" and "everyone was going nowhere". Farmers had yet to cash in on the grape rush. The first commercial vineyard wasn’t planted until 1973.

Marlborough's first commercial vines were planted in August 1973.

Marlborough's first commercial vines were planted in August 1973.

Topics of interest in the later half of the decade included the introduction of mini skirts, the changing length of boys’ hair at Marlborough Boys' College, and Blenheim being confused with Nelson three times on television.

"In the 60s, you went to work, you went home, went to the pub, moaned into your beer," Hancock said.

"It went round and round. No-one went anywhere. It was a town behind the times in a country behind the times."

One night at the pub, Hancock and his friends got onto the topic of escaped prisoner Trevor Nash, who was the central figure in a £19,000 payroll robbery in Auckland in 1956.

Nash and his gang broke into the Waterfront Industries Commission's offices, before they were arrested, escaped, and then arrested again in Australia.

Hancock was critical of how Nash executed his crime and said he hadn't been smart about it.

"You haven't got the guts to do what Nash did," Sergent said.

"Bloody oath, I could too," Hancock said.

The circle of friends joked that robbing a bank would be the only way to get out of debt. It was a fun idea; one that was easy enough to entertain during their regular pub sessions. On paper, the group decided, they had the perfect team.

The band rotunda, outside the Post Office, still remains, 50 years later.

The band rotunda, outside the Post Office, still remains, 50 years later.

Sergent once worked in the Blenheim Post Office, which connected to the Post Office Savings Bank, one of the few buildings in town that stored a large pile of cash.

He was familiar with the savings bank's layout and knew how someone could enter the building and steal the money in the strongroom without setting off the alarm. Hancock, on the other hand, knew how to use a blow torch, which could be used to get through the strongroom's door.

The group decided there would be little problem getting into the saving bank's strongroom. The door only boasted two thick plates. It shouldn't be a problem, providing of course, the alarm system could be bypassed.

Their theory was based on a 1935 incident, when the same strongroom door had to be cut with a blowtorch after its key jammed. Both Hancock and Sergent guessed the savings bank would have replaced it with the same type of door.

Hancock, self-described as a "smart b.....d who could do everything", thought the savings bank heist would be an easy in-out job.

Sergent was a "pretty laid back" but "private" man who thought it would be a laugh.

But surely this was just pub talk? A fantastical tale spun by a bunch of buddies to pass the hours. Until it wasn't.

A TWO-MAN JOB

On April 15, 1968, an Easter Monday, the men decided to rob the savings bank.

The two left in Hancock's small, dark green Chevrolet truck and drove to Sergent's house. There, Sergent hopped out and grabbed a small crowbar, a screwdriver, pliers and a box of tools.

Next stop was Hancock's work place to pick up a blow torch. Like most farms in the 60s, the piggery's barns and sheds were never locked.

When they got to the savings bank, in the centre of Blenheim, they parked in the yard next door, and went around the back.

The back door to the Post Office Savings Bank, used by staff.

The back door to the Post Office Savings Bank, used by staff.

They tried to force a window with the crowbar, but it didn't work. They were worried smashing the glass might draw attention to them.

Their attention turned to the rear door. A police report said the pair forced it with the crowbar, but Hancock said he used his shoulder. Regardless, the door gave, and the two gained entry to the savings bank section of the post office.

The pair made a couple of makeshift repairs so that the door could be locked again - preventing suspicion - before they inspected the strongroom door, just a few feet away.

It was painted a dull green and locked by a key. Its door had inside plates, a half-inch steel outside plate and an alarm over its lock.

"The electric alarm system was the tricky part," Hancock recalled.

"It was motion and heat sensored. If it went off, it would have alerted the police at the station, and we wouldn't know if we'd tripped it until it was too late."

But the blow torch should, in theory, cut a hole in the door, without triggering the alarm over the lock. A window was propped opened to provide a quick getaway, if required, and the blinds were pulled.

Hancock returned to the truck and drove it into the truck yard of the post office, before turning the truck off and unloading the blow torch equipment.

Once inside, he cut a hole about 20 inches by 16 inches into the outer plate of the door, while Sergent kept watch.

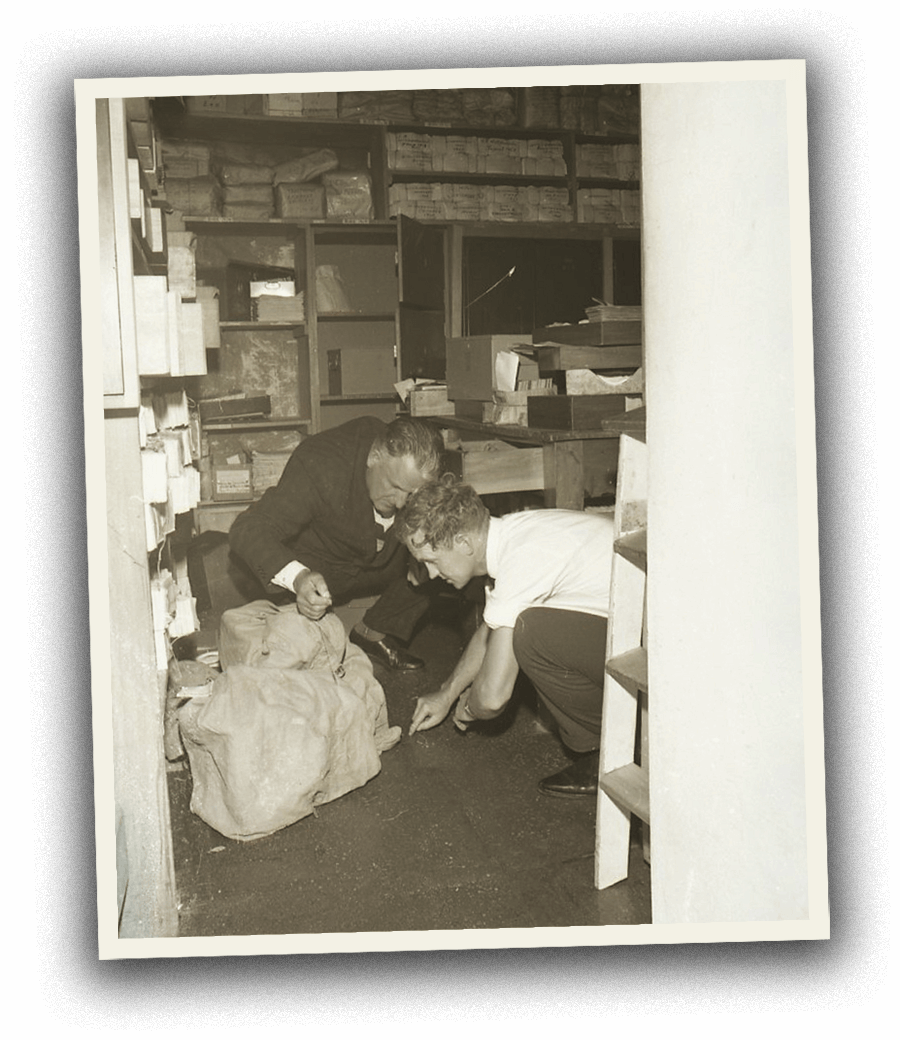

Detective Eric McLachlan, right, points out the hole in the strongroom door to Chief Postmaster J. J. Cronin, left, and savings bank manager J. D. H. Green. The white box on the left of the door is the burglar alarm 'safeguarding' the lock.

Detective Eric McLachlan, right, points out the hole in the strongroom door to Chief Postmaster J. J. Cronin, left, and savings bank manager J. D. H. Green. The white box on the left of the door is the burglar alarm 'safeguarding' the lock.

The back room had big, high windows that looked out onto a narrow road that sat nestled between the savings bank and the old Marlborough Club Hotel. The pair were worried bright flashes and sparks from the welding would catch someone's eye.

"I expected police to come in at any time and we'd have a laugh and have a beer," Hancock said. But no-one came.

A smaller hole was then cut in an inner plate, giving an opening large enough for the two to climb through. It took about 30 minutes to cut both holes.

The two crawled through the hole and into the strongroom. It held post office cash, postal notes, stamps and more cash from the Social Security Department.

JACKPOT

The strongroom had four wooden lockers, four steel lockers and several steel cabinets. Sergent pointed out the lockers that contained cash.

The friends used a screwdriver and their small crowbar to force the lockers open, revealing $21,000 in crisp banknotes.

Hancock then noticed a Gladstone bag.

"Geoff said to forget about them, but I was curious about the bag, so I had a poke around and found it had this toy lock on it," Hancock said.

"I broke the lock and found the bag had $30,000 inside. We later found out it was a social welfare payout from the Social Security Department that was left at the post office and wasn't supposed to be there."

It was the long Easter weekend. The department's Social Security funds, believed to total $30,000 (now about $535,190), were locked away for safekeeping.

At the time, the Social Security Department collected its money from the Bank of New Zealand, but its cash was kept at the post office, where social security payments were made.

In Blenheim, the department had its own steel locker in the strongroom of the savings bank where cash for paying superannuation beneficiaries and British pensioners were kept.

The two men put all their takings in the Gladstone bag and took the lot.

Hancock said there was so much money in the bag some was sticking out the top. The Gladstone bag was packed into the car, along with the blow torch and tools.

They left nothing but some steel cuttings and grit on the floor, half a dozen burnt out matches and a hole in the strongroom door.

Both Hancock and Sergent wore gloves and later destroyed the clothes they had been wearing by burning them with the blow torch.

After returning the blow torch to the workshop, the pair drove to Hancock's house and made a rough count of the cash. In the end, they weren't sure how much money they had taken or what to do with it.

Hancock buried a wad of cash under his dog kennel. The pair then packed the rest of the money into polythene bags, placed the bags into the Gladstone bag and, with rifles to make it look like they were going shooting, drove about 65 kilometres deep into the Marlborough Sounds bush.

Hancock and Sergent buried their loot deep in the Mahau Sound.

Hancock and Sergent buried their loot deep in the Mahau Sound.

The pair trekked to a remote location, where they dug a hole with a jungle knife and buried the Gladstone bag. Hancock and Sergent agreed that, if caught and interviewed, neither would give up where the money was hidden.

BEHIND THE CALM

The following morning, on April 16, savings bank custodian W. Steele arrived at work as usual, a Marlborough Express article said.

Steele found the main back door to the yard open but failed to notice the hole in the strongroom door on first inspection, due to the "good torch work".

"He was so fixated on finding the missing lock to the door, so much so that he missed the large hole we carved into the wall of the bank," Hancock said.

But eventually police were called, and word of the burglary soon spread through Blenheim and New Zealand.

Former Post Office teller Allen Diamanti holds a photograph of his 21-year-old self, taken in 1968.

Former Post Office teller Allen Diamanti holds a photograph of his 21-year-old self, taken in 1968.

Allen Diamanti was 21-years-old and working as a post office teller. The first he heard of the burglary was when he turned up to work.

"We had this supervisor who, once 8am came about, would stand there with the sign-in book and check you in as you came in, because he was a bit of a disciplinarian," he said.

"So here I am, running late and running to work, just about to barrel into the door, and this policeman who must have thought everyone had arrived yelled out, 'Hey, where are you going?'"

Diamanti was about to go into the staff quarters. He saw powder marks on the door, which he later realised was police dusting for fingerprints.

The policeman intercepted him and told him there had been a burglary and directed him to go through the post office's front entrance, which was used by the public.

"That's when I first realised, we'd been robbed," he said. "So, we did have to open that day. There wasn't any closing down."

But behind the calm facade, there was a flurry of activity.

Blenheim's two-man Criminal Investigation Branch - Detective Eric McLachlan and Detective Constable Bert Sinclair - was about to be bolstered by detectives from Christchurch, Nelson and Wellington.

From Christchurch came Detective Sergeant G. T. Dawson and Detective T. J. Gorman. Fingerprint expert Detective B. Gundesen came from Wellington, and from Nelson, Detective Sergeant A. W. Hedwig, who took over the case from McLachlan.

Shortly after 1pm, the manager of the savings bank, J. D. H. Green turned the key in the strongroom door and opened it for the first time in the presence of police.

Their worst fears were confirmed. Thousands of dollars were missing.

"It was something like what you'd see out of an old movie," Diamanti said.

"[The door] was a solid, old, iron thing, painted deep green and it had a key in it about two hand spans long. The strongroom itself was very low. It would hardly be 7-feet tall."

He said the strongroom boasted solid concrete walls "all the way around". The savings bank was built in 1878, 90 years before the heist.

"The door to the strongroom would be an age old," Diamanti said. "To modern welding equipment, even in the 60s, it would be like a hot knife going through butter."

Gundesen was the first to step into the room, in the hope of recovering some fingerprints. Nelson police photographer Constable C. R. Barron followed, taking a series of pictures, before Hedwig entered the strongroom with Green.

An audit showed $24,341.50 from the New Zealand Post Office and $26,630.42 from the Social Security Department was gone, for a total steal of $50,971.92 - about $908,420 today.

Police said at the time the heist trumped Nash’s £19,000, the same crime that sparked Hancock and Sergent’s daring escapade. New Zealand switched from the pound in July, 1967, the year before the post office heist. In reality, police were comparing $50,000 to £19,000, and hadn’t accounted for inflation. Nash’s steal would have come in at $55,000 in 1968.

People line up to switch their money from pounds to dollars on Decimal Currency Day on July 10, 1967.

People line up to switch their money from pounds to dollars on Decimal Currency Day on July 10, 1967.

Then Police Commissioner G. C. Urquhart said the heist was “probably the biggest in New Zealand's history”.

“It eclipsed the Auckland Waterfront Industries Commission burglary of 1956 in which £19,000 was taken and the burglary of a Riccarton, Christchurch bank about three years earlier when about £12,000 was stolen,” an Express article said.

"They tried not to have too much money overnight, but you've got to remember that Friday night used to be late-night shopping and the bank would stay open until 8pm," Diamanti said.

"You'd have to step off the footpath to walk past Thomas's [shopping mall] on a Friday in those days. The whole town would be chocker."

"I think it was publicised as the largest cash robbery in New Zealand at the time, which sounds like it was hoards of money," Diamanti said.

Police told media that from initial observations, it appeared the burglars knew what they were doing. They said the burglars had, in all probability, surveyed the savings bank beforehand and picked their moment carefully.

With no fingerprints, no witnesses and little evidence, police started what was the largest manhunt in New Zealand history.

As police searched far and wide for the missing money, Ray Hancock was using it to pay his bills - in the post office he had just robbed.

Police were stumped. About $50,000 had been stolen from the Blenheim Post Office Savings Bank in Blenheim - “a record for New Zealand” - but there were no witnesses and little evidence.

Someone with inside knowledge of the savings bank's layout must have committed the heist, police told the media.

Their theory was based on how the door closest to the savings bank's strongroom had been forced, and the strongroom had been broken into on April 15, an Easter Monday, when it was holding a lot more cash than usual.

Police checked the alibis of every known criminal in New Zealand capable of breaking into the savings bank over the next few days, but found that none of them had been in Blenheim over Easter.

They also ran checks on all past and present employees of the Blenheim Post Office and the Social Security Department, who would have known intimate details on the savings bank. No-one caught their eye.

A broken window from the savings bank was removed to check for fingerprints, after none were found in the strongroom.

Police issued a statement which said they were looking for a pale blue 1957 Holden station wagon, after several people reported seeing it on Monday afternoon with engineering tools in the back.

But despite numerous phone calls about the whereabouts of a car matching the description, the vehicle was never found.

Two days later, after the fingerprint check of the broken window revealed nothing, the empty cash boxes and strongroom door were taken to Wellington for further examination.

It was another dead end.

"The police said they had a huge file of evidence, but they had nothing," Hancock laughed.

On April 18, three days after the heist, businesses belonging to the Marlborough Chamber of Commerce got together to discuss the burglary.

One member accused the post office of being "exceedingly lax in its security arrangements".

Bank of New Zealand Blenheim manager J. R. Dickens expressed his "dismay" at the saving bank's security. His own bank was equipped with an anti-blow safe behind a combination safe.

"That's where the cash is kept, not in wooden boxes," Dickens said.

The economic conditions of the 1960s were causing repercussions in the criminal world, he said, giving his thoughts on the motive.

"We might count ourselves lucky that it was a government department and not a private concern that was the target," he said.

Blenheim-based Inspector A. Hunt reassured members that the culprits would not be on the run for long.

"There is a man or a group of people who have set a record for New Zealand that they won't be able to skite [boast] about," he said.

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

But Ray Hancock, one half of the duo behind New Zealand's biggest heist, was treating it as "a joke".

He started taking "shiny and new" notes from his newly acquired wealth - some of which he'd buried in his backyard - back into the post office to pay his bills. He would crinkle them and rub them in dirt first to make them look old and used.

Hancock thought it was "hilarious" he was able to use the money around town, despite the consecutive identification numbers on the notes. Nobody noticed. Most Marlburians were probably still reeling from the sinking of the Wahine less than a week earlier.

"I took them into the post office to pay off my phone bill, which was overdrawn," Hancock said.

"While I was there, I asked how the investigation was going, and the man said the hole in the bank door was the sweetest they'd ever seen, and that they had even got in an expert from Australia."

He also paid for his girlfriend's car insurance, which cost $4 (now about $115).

But not everyone was as oblivious as Hancock thought.

Ray Hancock's old boss and "close friend" Ross Simonsen. Hancock worked as an engineer/mechanic at the Simonsen's Brothers commercial piggery.

Ray Hancock's old boss and "close friend" Ross Simonsen. Hancock worked as an engineer/mechanic at the Simonsen's Brothers commercial piggery.

The piggery Hancock worked for, Simonsen Brothers, was co-owned by brothers Lloyd, Ross and Bobbie Simonsen. Ross Simonsen said it took the brothers just a few days to suspect their "polite, clean and tidy" employee Hancock.

"We figured it out before the police became involved," Simonsen said from his house in Witherlea, in Blenheim.

A description of the crime scene in the Marlborough Express tipped them off, he said

"It was the way he welded stuff, the way he dropped his matches. But we didn't confront him. We weren't sure, and you've always got to give people the benefit of the doubt," he said.

"Besides, he was a good worker and we didn't want to lose him. Good workers were hard to come by. It was hard to fill vacancies then."

Simonsen said Hancock was a brilliant engineer, building trailers, a grain system for the piggery and a stock car, which Simonsen would drive.

"He could build anything from nothing," he said. "He was just a happy-go-lucky guy. Not a care in the world."

Hancock with a rotary dial phone strapped to his hip at a Hunters, Brewers and Gatherers Society mid-winter feast. The picture featured in the July 1994 addition of 'The Picton Record'.

Hancock with a rotary dial phone strapped to his hip at a Hunters, Brewers and Gatherers Society mid-winter feast. The picture featured in the July 1994 addition of 'The Picton Record'.

On April 19, Hancock went to burn the car floor mats of his small truck, which he had placed on a rubbish pile at work, in case he had walked dust and dirt from the crime scene into his car.

But when he turned up, the floor mats were gone.

"The police had come down to check the gas plant out, which they were doing all over Marlborough with all gas plants," Hancock recalled.

"When I got down there the police had already been in and I thought, 'Oh Jesus'. And I said to Lloyd [Simonsen], I said, 'the police down there, did they take those floor mats?'

Lloyd, a close friend, said he had taken them out and burnt them.

"He had a wife and kids, and I didn't want to get him into trouble, so I told him [about carrying out the heist]," Hancock said. "He collapsed on the ground, he couldn't handle it."

It was then that Hancock called the police and turned himself in.

"I rang them up, told them I'd done it, and the police told me after about three hours they were going to book me for hindering a police investigation," he said.

"They didn't believe me. I said, 'right, I'm buggering off back to work, I've got work to do down the way'. They said, 'this is you and the warped sense of humour that you've got', because I had quite a bit of a reputation.

"And one of them said, 'no, he knows too much'. It was Dawson, the second in command."

Hancock said he didn't consult his friend and heist partner, Geoff Sergent, before turning himself in.

"I went at it alone. He was way out in the field working with Land and Survey and we had already agreed if something came unstuck, we would go in on our own," he said. "But he wouldn't let me go it alone."

Former Post Officer teller Allen Diamanti said he heard how the pair had owned up, but police kicked them out of the station.

Police had already told newspapers and television media the heist was so well carried out it had to be a national gang or someone from overseas, Diamanti said.

"And, of course, it turned out to be the complete opposite, didn't it? That was why all the locals were laughing when they found out who did it," he said. "One had the knowledge and one had the skill."

MONEY WAS MISSING

Later that night, Hancock and Sergent were arrested and interviewed by police. They admitted stealing from the savings bank.

They were charged with "breaking and entering a building" with "intent to commit a crime" by Christchurch Detective Sergeant James Dawson.

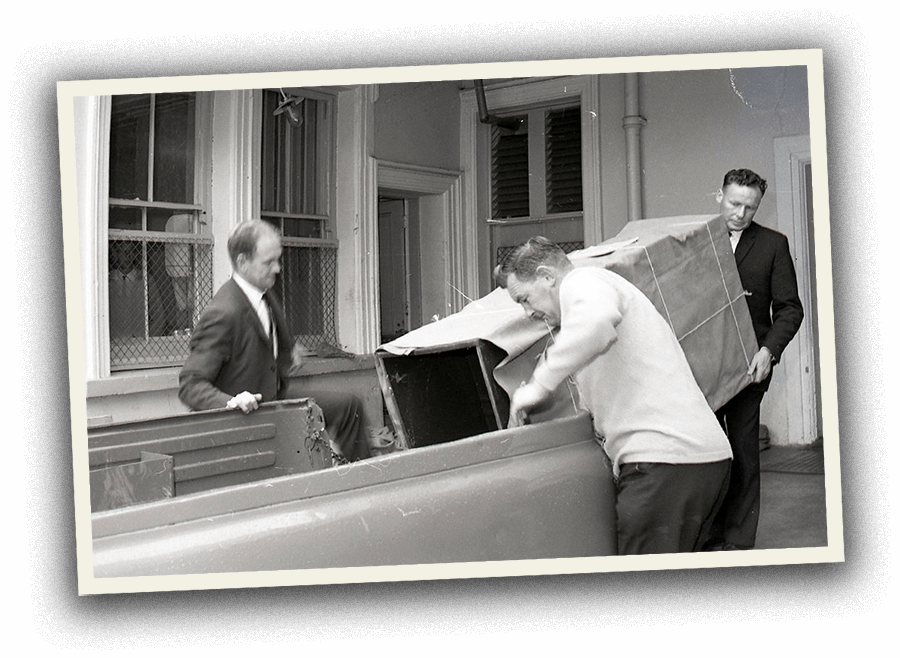

The next morning, the pair led detectives to the area in the Mahau Sound, part of the Marlborough Sounds, where they'd buried the Gladstone bag.

It took them a few hours of searching in rough scrub before they found the place where the money was buried, about 60 centimetres deep and, in spite of being packed in canvas and plastic bags, it was soaking wet with ground and rain water.

The front page of the The Marlborough Express on April 20, 1968 reported most of the $51,000 had been recovered.

The front page of the The Marlborough Express on April 20, 1968 reported most of the $51,000 had been recovered.

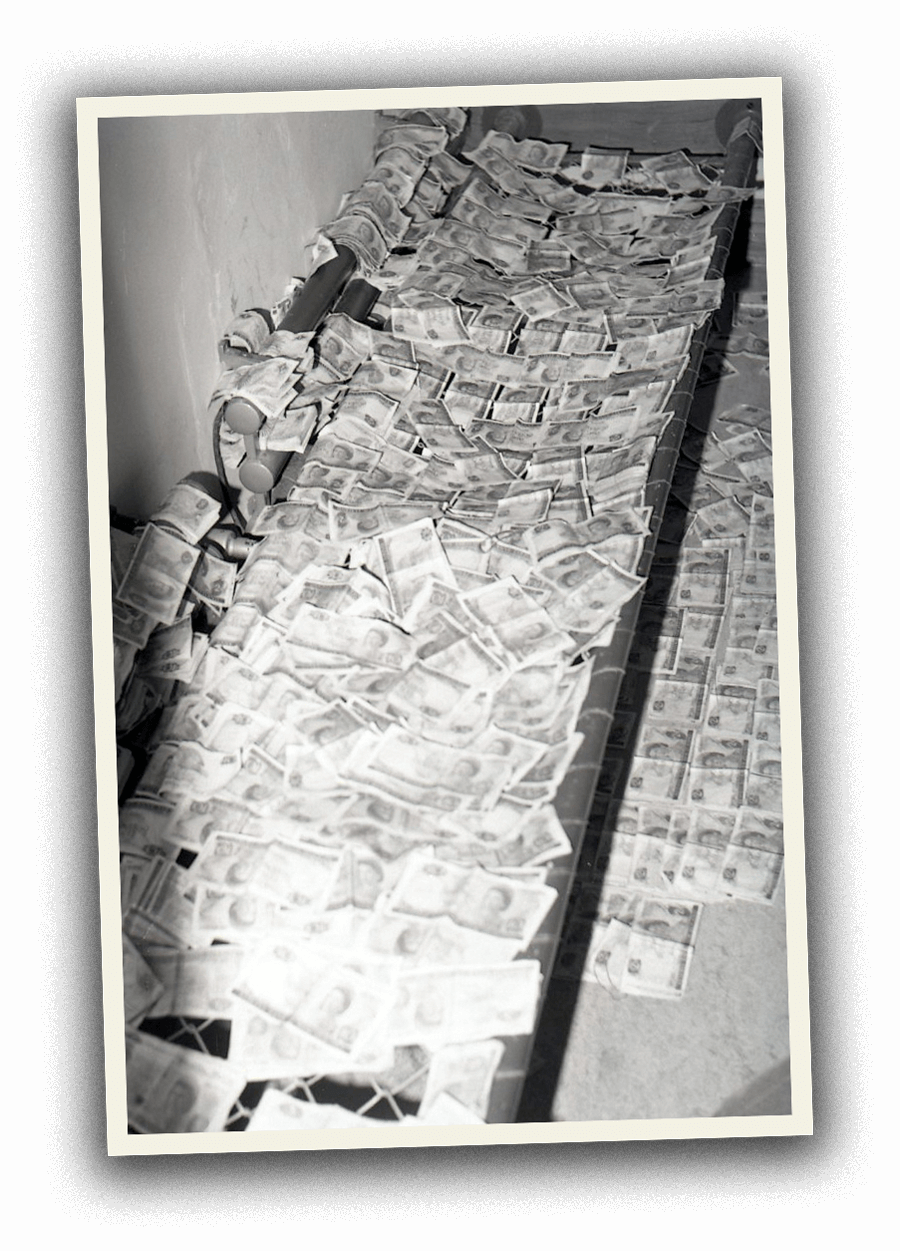

The money was taken to the Blenheim Police Station. Police left the paper notes to dry out. Hancock and Sergent were not so lucky.

The pair were taken in their wet, mud-splattered clothes to the Blenheim Court and remanded by R. A. J. Marston JP, to appear before the Blenheim Magistrate Court on April 26, 1968.

Sergent had on a red checkered shirt, neat trousers and shoes. Hancock was wearing a light blue football jersey with the number '20' on it. They were the same clothes they had on when they were arrested.

Sergent and Hancock, in his Central rugby jersey, before they appeared in the Blenheim Court, accompanied by Constables A. F. Schultz, left, and T. R. Lyttie.

Sergent and Hancock, in his Central rugby jersey, before they appeared in the Blenheim Court, accompanied by Constables A. F. Schultz, left, and T. R. Lyttie.

"[A photographer] got a photo of me with my Central jersey number on the back, which was a bit deflating for me because ... I was the fulltime centre or wing. I wasn't a reserve, but that was a reserve number," Hancock said.

A news report of the hearing said Hancock "kept smiling" as the charge was read. The pair were taken into custody until their next appearance.

The police station became a counting house when police, Post Office and Social Security Department staff banded together to tally the cash.

They found $46,722.61 in the Gladstone bag, which left $4249.31 unaccounted for.

"The missing money claims were rubbish ... neither the police nor the bank tellers were really sure how much was there to begin with," Hancock said.

"The whole damn show was wide open. There was money loose everywhere. Anyone could have seen what had happened, picked up a wad [of cash], [to] stick it in their pocket."

Police spoke with Simonsen's older brother, Lloyd, who was also Hancock's boss, about the burglary.

After speaking with him, police wanted to empty the farm's two fully stocked 100-tonne grain silos to see if there was money in them, Ross Simonsen said.

One of the two 100-tonne grain silos that used to sit on the Simonsen farm. Police considered emptying the silos to see if the cash from the savings bank had been hidden inside.

One of the two 100-tonne grain silos that used to sit on the Simonsen farm. Police considered emptying the silos to see if the cash from the savings bank had been hidden inside.

"But we said 'no' as Ray was scared of heights. It was his one fault. You had to fill the silos from the top, you see, and he would never go up there," he said.

"There was plenty of talk about it, basically about how he did it and why he did it. But he was that sort of guy, do it as a devil. A sudden impulse and he'd do it."

On April 23, police continued to search for the missing money, despite pouring rain, as they believed used notes might have been buried separately to new ones.

A small army of police searched the ridge between Mahau and Kenepuru sounds in hopes of finding the missing money, an Express article said.

But it was like searching for a needle in a haystack. The terrain was steep, gullied and overgrown, and the rain dampened spirits.

No more cash was ever found.

STANDING ROOM ONLY

Hancock and Sergent pleaded guilty in the Blenheim Magistrate's Court on April 30, almost two weeks after the heist.

The pair weren't charged with bank robbery, because that implied intimidation was used. They also weren't charged with theft, as they had, for the most part, returned the money.

The hearing attracted a lot of spectators. For the first time in years, it was standing room only in the court's public gallery.

Former solicitor Anthony Willy focused on Hancock's good character when he appeared in court.

Former solicitor Anthony Willy focused on Hancock's good character when he appeared in court.

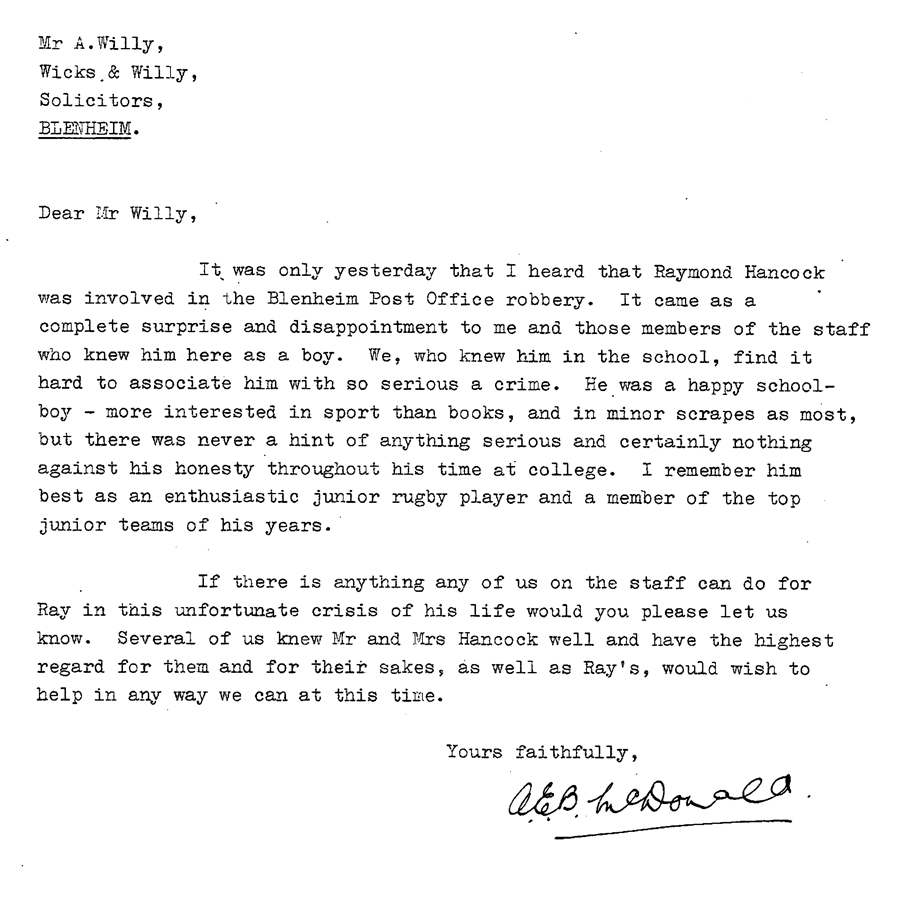

Hancock’s lawyer Anthony Willy recalled getting a letter from Hancock's former teacher and rugby coach, Upper Hutt's St Patrick's College school teacher Alec McDonald.

"We, who knew him in the school, find it hard to associate him with so serious a crime," McDonald wrote.

"He was a happy schoolboy - more interested in sport than books, and in minor scrapes [at] most, but there was never a hint of anything serious and certainly nothing against his honesty through his time at college."

While in remand the pair were put into a cell at the Nelson Police Station.

"The cell had bars on the window that previous criminals had been working on during their time in isolation," Hancock said.

Hancock said to Sergent if they pulled one corner section of the bars, the whole thing would fall apart. He was right. Police later came in to see the two men with the bars on the bench beside them.

"The police cried 'bloody hell' and laughed," Hancock said.

On May 17, the pair appeared in the Supreme Court for sentencing.

THE BIGGS CONNECTION

Hancock said the whole thing was a "lighthearted affair" until Judge Wilson got involved.

Wilson was paranoid the pair would get the same good-favoured public treatment English robber Ronnie Biggs received several years earlier, he said.

Mug shots of Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs, later displayed at the National Archives in London.

Mug shots of Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs, later displayed at the National Archives in London.

Biggs was part of the gang behind England's 'Great Train Robbery' of August 1963. He was caught, sentenced, and later escaped from Wandsworth Prison, in London, in 1965.

He escaped arrest by travelling the world and becoming a public icon in the process, with wax figures, television dramas and newspaper cartoons done in his name.

Cartoons poking fun at the Blenheim Post Office heist and the then-unknown culprits had also been published in New Zealand newspapers.

A Marlborough Express cartoon imagining Hancock or Sergent living the high-life overseas.

A Marlborough Express cartoon imagining Hancock or Sergent living the high-life overseas.

"The judge was incensed by the cartoons. He got septic, yelled about how much we were like Biggs," Hancock said.

"It was Biggs this, Biggs that, to the point where I asked the cop with me if I was at the right hearing, because there was just so much talk about Biggs.

"The judge got furious at that. He jumped over his stand and looked just about ready to hang me."

Hancock said the hearing lasted 90 minutes, but the court transcript was just three paragraphs long. Looking at the transcripts today, Hancock said: "Where's all that talk on Biggs? The screaming, the yelling?"

Judge Wilson sentenced the pair to three years in jail, saying it was one of the "saddest cases" he had seen.

"Neither of you had any real need of money, neither of you had done anything dishonest before in your lives, so far as one can make out, and I do not think either of you will ever do a dishonest thing again," he said.

"And yet there was some basic defect in your ethical makeup because you deliberately settled down and planned a burglary for the purposes of stealing money from the Post Office Savings Bank."

He said had it not been for their good character and the fact the heist was their first offence, the pair would be looking at "a very lengthy term of imprisonment". Wilson said while neither man needed a long stint in prison, prison time was "necessary" to deter others from trying their luck at robbing banks.

'HE SHOULD HAVE KEPT IT'

Hancock and Sergent served their three-year sentences in Addington Prison, Paparua, or Christchurch Men's Prison, Rolleston Prison, and Mt Crawford Prison.

"We went to bloody near every prison in the country," Hancock said. "I'd never seen so much of New Zealand."

Each time they arrived at a new prison, their reputation for pulling off one of the biggest heists in New Zealand made them "the bosses", he said.

A faded photograph of Hancock, with a large catch, captioned 'The Boss', sits above the captain's chair in his house boat.

A faded photograph of Hancock, with a large catch, captioned 'The Boss', sits above the captain's chair in his house boat.

"The lower downs had to make an appointment if they wanted to see us. People thought I was New Zealand's answer to Ned Kelly."

Sergent served two years and three months before being released, while Hancock served two years and four months.

"Looking back, I would tell my younger self not to tell [the police] and don't give back the money. It would have bought about 10 houses back in the day," he said.

"The police said we should have never given it back, the legal professions said we should have never given it back. They brought a priest that came around to see me, he said we should have never given it back."

Hancock lives on his boat in Picton Marina.

Hancock lives on his boat in Picton Marina.

But despite having "no guilt, no shame, no regrets" about the heist, Hancock said he couldn't do it now.

"The ATMs take all the skill out of it," he said.

Down at his local pub in Picton, Oxley's Bar and Kitchen duty manager Lauren Cunningham said Hancock was "definitely a character" and "someone who had lived quite a colourful life".

She said Hancock had a favourite spot at the end of the bar where he would lean himself against the wall and have a drink.

Now 80-years-old, Hancock said he was once "bulletproof", but now "full of bullet holes".

He signs his name "What's left of Ray Hancock". It's a nod to his frail legs, suspected methyl bromide poisoning and being blind in one eye, he said.

"He does enjoy his notoriety," Cunningham said.

"I didn't believe him the first time he told me [about the burglary]. He compares himself to a train robber, and old American bank robbers. He tells other customers all about his adventures."

Ray Hancock, New Zealand's own Ned Kelly or Ronnie Biggs.

Ray Hancock, New Zealand's own Ned Kelly or Ronnie Biggs.

Hancock recalled a time when he told one woman at the pub and she didn't believe him. She came up to him later and laughed, saying: "You really are a bank robber, I thought you were a load of s***."

*Sergent moved to Australia in the 1990s. He could not be reached for comment, and his family in Blenheim wanted the matter "dead and buried".

Words: Chloe Ranford

Visuals: Scott Hammond and Ricky Wilson

Design & layout: Aaron Wood

Editor: Ian Allen