Detective sergeant Mark Worner was on his way to hockey practice when he saw a strange object at the side of the road.

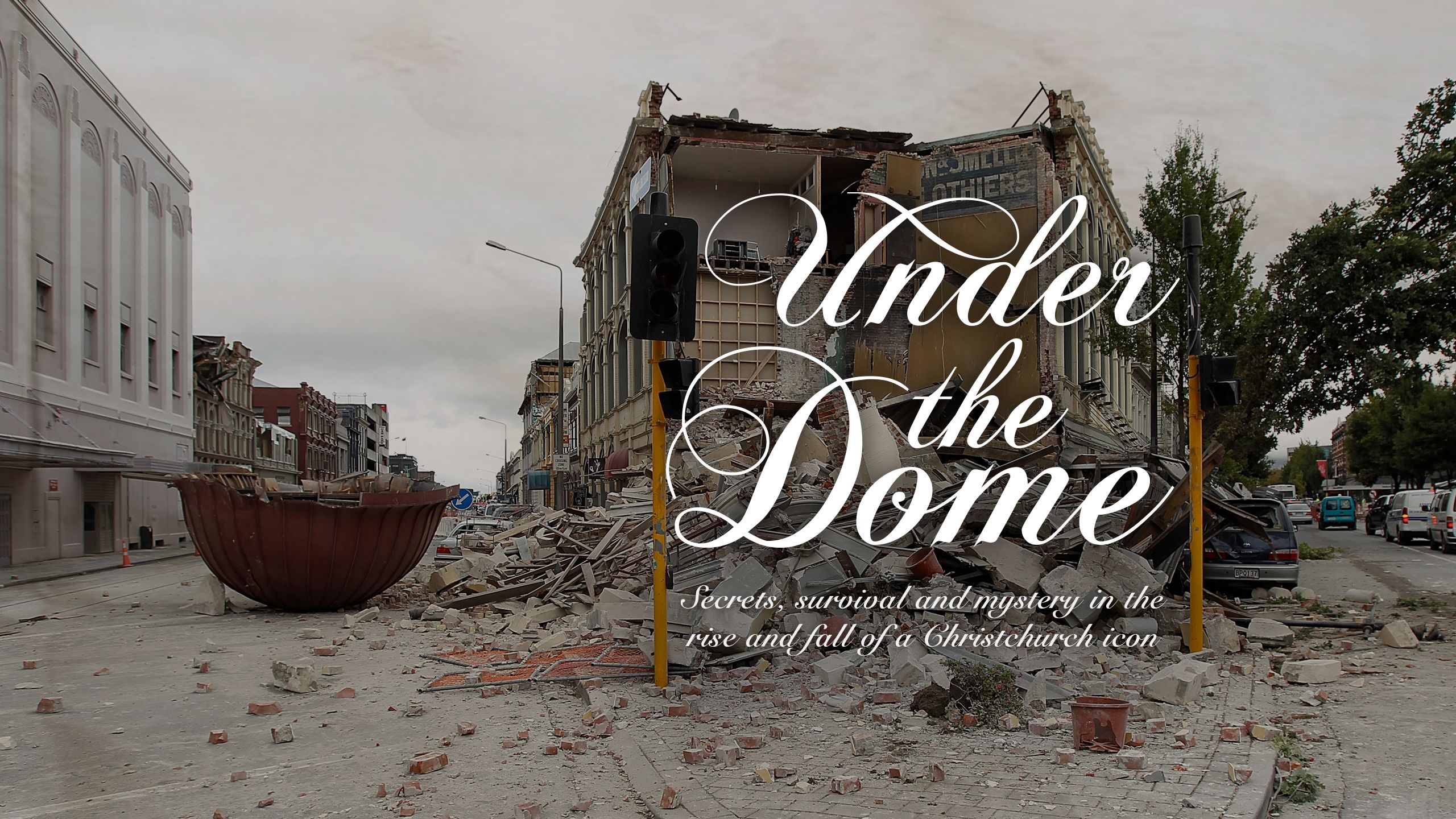

It was three months after the 2011 earthquakes and he was driving along Momorangi Crescent in the north Christchurch suburb of Redwood.

He immediately recognised the object as a copper dome that had stood above central Christchurch for nearly a century.

He didn’t know it at the time, but Worner was the last known person to see the dome.

When he passed the spot a week later, it had gone.

The dome was hoisted to its perch on the corner of Lichfield, High and Manchester Sts in about 1912. It sat atop the curved landmark that became known as the ANZ Chambers building and could be seen down High St from many blocks away.

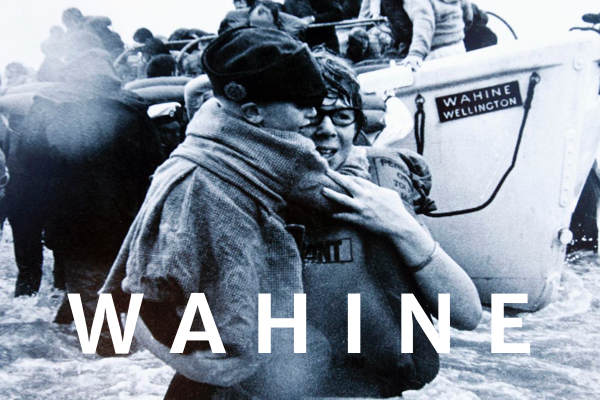

On February 22, 2011 the building collapsed in the earthquake, sending that dome plummeting into the street. The three-storey building fell on a woman working on the ground floor, burying her alive.

The dome landed upside down in the middle of Lichfield St, upturned like a giant teacup.

And then it vanished.

Police officers spent months trying to solve the mystery. Was it stolen and sold for scrap or scooped up with all the other rubble and sent to landfill?

Over the decades, the building had hosted bankers, sex workers, rock videos and architects. It was the scene of hidden secrets, miraculous survival and a final enduring mystery.

The dome was a mirror of the city’s changing fortunes over a bustling century. Through the story of the dome can be told the strange history of a place called Christchurch.

Fall

Holly White had only been working at World for a few days when the earthquake struck.

It was February 22, 2011 - the building's last day. She was the only person in the fashion boutique when the shaking started. The two storeys above her collapsed, sending her plunging into the basement and entombing her in rubble.

"I heard the sound of the whole building coming down," she told the New Zealand Herald in 2011. She declined to comment for this story.

"Something hit me on my back. On my head. And then it went black, the blackest black I have ever seen."

"I knew I wasn't unconscious but at that time I knew I was going to die. You never expect something like this to happen to you. I started crying and thought about all the people I loved. It was an out-of-body feeling."

When the shaking stopped she was trapped in the rubble and the dark. She eventually managed to free herself and found a larger space at the back of the basement.

"I went into survival mode. I knew I had to get out of the rubble."

She saw a ray of light above her, looked up and started screaming for help.

Outside was chaos. Buildings alarms rang out. The Reuben Blades building on the other corner had collapsed. Cars fled the scene, weaving through the rubble.

Jono Moran from the fashion boutique next door and David Pai from the cafe on the other side were looking for White. They asked around in the street, but no one had seen her. So they climbed on the pile of rubble that was the dome building and started shouting Holly’s name.

When they got a response they peered down through a hole in the rubble and saw White in the basement. She was covered in dust, so they could only see her eyes and teeth in the gloom below.

It was hard to reach White from the top of the rubble, so Moran lowered Pai into the hole by his ankles. White grabbed him and clambered to the light.

And then she was out, covered in dust and blinking in the daylight. She had a few bruises, but was otherwise fine. She was shocked to be alive.

"I still get emotional when I think about it," White said in 2011.

"They didn't expect to see any survivors. And there I was with arms and legs. If I had been there any longer it would have caved in. Once I got out I had this buzzing feeling."

David Pai and Jono Moran talk about their rescuing Holly White. Video: Charlie Gates/George Heard/Daniel Watson

White and Moran walked together, her in bare feet because she had lost her shoes in the building, to the medical clinic on Moorhouse Ave.

“Because a building had just collapsed on her I thought we should get her checked out,’’ said Moran.

Behind them the building was a pile of rubble.

Rise

The dome building was completed by 1912, but its landmark status in later years was thanks to the city’s founding plan.

The original plan for Christchurch was mapped out in 1850 and imposed a grid of streets across the gentle curves of the Avon River.

Grid cities had their roots in ancient Greece and Rome, but found favour among 19th century city planners. New York was laid out on a grid in 1811, while Melbourne followed suit in 1837.

The original Christchurch grid was broken by two diagonal streets. Whately Rd later became Victoria St and Sumner Rd became High St. These diagonal streets created distinctive triangular corner sites where buildings could command the streetscape and become landmarks.

The dome building was eventually built on one of these corner sites on High St. In 1909, the lease for the site was transferred to one of the city’s biggest architectural firms, Clarkson and Ballantyne. The firm had been busy since forming in 1899, making their mark on the growing city with grand houses and prestigious stone buildings.

High St was the perfect place for the thriving firm, with The Press noting in 1920 that “in recent years the business centre of Christchurch has swung steadily in this direction.’’

The firm took out an ad in May 1907 calling for tenders to build a “handsome brick and stone building’’ on the corner. They worked up a design that took advantage of the corner site, standing proudly like the prow of a ship and visible from two blocks away on Hereford St.

Like much of New Zealand’s early architecture, the building’s style was drawn from Europe. Edwardian baroque revived the decorative dome, an architectural flourish that had its roots in ancient Rome and later the Italian renaissance. The building’s copper dome originally featured a large decorative pole on top, which was still in place in 1947, but had gone by 1951. Perhaps it was removed after a couple of strong earthquakes in north Canterbury in 1948.

The new building was completed on High St by 1912, becoming a home for Clarkson and Ballantyne on the top floor, dentist Jos Francis Lewers, and tobacconist Harry Hulston on the ground floor. The building filled out the corner, extending an L-shaped building constructed a few years earlier for Graham, Wilson and Smellie drapers.

The architecture firm had grand double doors opening out to the second floor balcony on the corner. Clarkson and Ballantyne Architects was written in bold letters above the door. Clarkson was written on the glass of one door, while Ballantyne was written on the other.

Over the next few decades, the building was home to music teachers, a confectioner and a tearoom.

It’s prestige was confirmed when the ANZ Bank took up residence in 1954, but faltered when it left in 1982. By then, High St was in decline.

In 1987, a company listed as the Sunrise Health and Fitness Studio moved in to the top floor space designed for the building’s original architects.

It was a brothel.

Decline

The Sunrise brothel featured in a music video made that same year.

In one shot, the camera starts at the dome and then tracks down the tower, past the now peeling paint and the embossed stone letters reading ANZ BANK CHAMBERS, past the sign for the Sunrise Sauna and joins The Bats guitarist Robert Scott on the balcony, strumming the chords to Block of Wood. The rest of the band join him on the other balconies stretching down High and Lichfield Sts.

The Bats bass player Paul Kean said they chose the building for its striking looks.

“It was a lovely looking building and I liked that tight corner. I thought it would be great for swooping around.”

So they got some out of date 16mm film from music television show Radio with Pictures and hired a cherry picker from a friend for mate’s rates.

They raised the cherry picker on the corner of Lichfield and High Sts early one Sunday morning.

“Sunday morning in those days was pretty deserted in town, so we could set up without any permits,’’ said Kean.

“It was kind of shaky up there on the cherry picker, so the camera person was a bit nervous. It looks pretty damn deserted in town. You can see that in the video.’’

The music video captures the building at a moment when it was perhaps a little unloved. A cafe that later moved in to the ground floor captured the mood. It was called Krusty Korner.

But Anna Reed loved the building. She was a sex worker in the Sunrise Sauna and took pride in the building. She would vacuum the steep stairs that led to the brothel. She would also lug bags of coal up those stairs so she could light the original fireplaces, formerly used by the bank to dispose of unwanted documents.

The top floor now housed the brothel, featuring a large circular room with spa pools and a mural around the curving wall. Thursday nights were busy because civil servants got paid. Mondays were busy because farmers would come into town.

Reed loved the daylight that poured in through the tall, top floor windows, designed to cast light on the drawing boards of architecture firm Clarkson and Ballantyne.

“I liked the openness. Most of the massage parlours were windowless rabbit warrens.’’

The large windows also served a second purpose. She could hide her cash in the large hem of the curtains.

“You always had to worry about hiding your money.’’

It was never wise to carry large amounts of money as a sex worker in 1980s New Zealand. If you were stopped by police, they would use the cash as evidence you were soliciting sex, which was illegal.

The building remained a brothel until early 2000 when a man threw a molotov cocktail up those narrow stairs and the fate of the building changed once again.

Rebirth

Andrew Hodge and Craig McWilliams were sitting outside their gift store on the ground floor of the ANZ Chambers building one morning when they smelt smoke. It was the fire damage from the molotov cocktail.

That day, the owner of the building, Dave Kettle, approached the couple and asked if they wanted to buy it.

“He said they could no longer insure the building with a brothel in it so they couldn’t afford the mortgage anymore,’’ said Hodge.

They bought the building for about $500,000 in April 2000.

And then began an unexpected adventure as they slowly restored the building and uncovered the secrets of its past.

The first job was to remove the charred wood from the fire in the stairwell. When they removed the wooden clapboards, they discovered a painted sign for Graham, Wilson and Smellie drapers from the 1900s.

“We left it in the hallway and framed it off,’’ said Hodge.

“All those things we discovered we made into features.’’

The building held many secrets.

They discovered decorative pressed tin hidden behind false ceilings and found the bank's original glass doors nailed behind false walls. They rehung the large doors in their original place on High St and restored the tin ceilings. Large, metal vaults were still in the basement from the building's time as a bank.

On the top floor, everything from the brothel was left behind.

“There were about four rooms. One was pink. There was a bondage room and a Greek room,” said Hodge.

“We left it all up there. My mum would come round for a meal and she loved it. We had a lot of different dinner parties up there. It was so much fun.’’

They enjoyed the building’s three fireplaces on chilly evenings.

“An elderly woman came into the shop one day, she was in her 80s, and she told us her job at the bank was to burn all the paperwork in the fireplaces.’’

And then there was the dome. It was above the top floor and could be accessed by climbing a ladder and squeezing through a small hatch in the ceiling.

“We got up in the dome. We took out buckets and buckets of pigeon poo, old nests and dead birds. We got rid of all that.’’

Carved into the walls below the dome were the initials of the labourers who helped build it, along with the date.

Once they had cleaned and restored the dome, they cut a hole in the ceiling of their apartment below so it acted as a light well.

Their restoration work dispelled the myth that the dome had been used as a loft for messenger pigeons when the building was a bank. There was no door to access the dome, but pigeons roosted there because the glass windows had smashed.

They also restored the outside of the building, repainting the peeling facade and putting 92 pots of red geraniums on the balconies.

“We felt this civic responsibility to keep the geraniums looking really good,’’ said McWilliams.

“I would spend a whole day dead heading them on two floors and watering them. It took all day.”

Slowly the neighbourhood started to change around them. The Christchurch City Council had long wanted to use heritage buildings on High St to help regenerate the city centre.

The building led the rebirth.

In a 1998 report for council, architect Ian Athfield said regenerating the dome building’s block was “one of the most important initiatives for the rejuvenation of the inner city of Christchurch and cannot be compromised.’’

Council launched a project to smarten up heritage buildings on High St by removing excess wiring, signage and unsightly fire escapes. They also repainted and illuminated key buildings.

Over time, fashion boutiques and cafes began to move to High St, attracted by the characterful heritage buildings and the relatively cheap rent.

At around this time, the dome building got some hip new neighbours. Fashion boutique Indefinite Definite opened next door on High St in 2008 and a new coffee shop opened on the other side on Lichfield St in 2009. They were run by Jono Moran and David Pai, who would rescue Holly White just a few years later.

“I managed to get a cheap deal. You could see that it had the potential to become a really interesting area,’’ said Moran.

The area’s new hipster credentials attracted investment.

From 2004 to 2007, rents on the street doubled. Kensington Park Investments purchased three heritage buildings on High St around this time and invested heavily in restoring them to attract prestige tenants to the area.

Council also invested in the area, spending $11.5m in 2009 to extend the tram network down High St to Tuam St.

In 2009, World fashion boutique became part of the High St renaissance and moved into the ground floor of the dome building.

Inevitably, Hodge and McWilliams were swept up in this wave of investment.

A real estate agent approached the couple in 2007 about buying the building for a bank. Eventually they sold it for $1.3m in September 2007 to a local investment firm.

“We never planned to sell it,’’ said McWilliams.

“We had spent a lot of money and a lot of hours restoring that building, but we used to say it doesn’t matter, because the building is going to be there for another 100 years.’’

Mystery

On the afternoon of February 22, 2011, the building was a pile of rubble.

One of the geranium pots was intact on the pavement. The painted sign for Smellie drapers had been revealed by the collapsed building for the first time in over a century.

The copper dome was sitting upside down in the middle of Lichfield St. It would remain there for a few days and then mysteriously disappear.

On April 26, 2011 constable Mark Boddy was tasked with finding out what had happened to the dome.

The only information available on the investigation is the police file, released in a heavily redacted form under the Official Information Act. Bradley declined to comment. Boddy did not respond to emails and calls for comment.

The file shows that Boddy started his search by contacting scrap merchants, talking to people who had seen the dome in the days after the quake, and printing out a list of contractors authorised to work in the city centre red zone cordon, erected around the four avenues immediately after the 2011 earthquake.

“How would/could this be moved?” he wrote in his notes.

He also contacted Bradley to “put his mind at ease in respects of other items such as porcelain baths and items that could be seen in the rubble.”

He found Constable James Mason, who remembered seeing the dome upside in the street on the day of the earthquake, but crushed and moved to the side of the road by February 24.

Detective Jeremy Gunn checked to see if the dome had ended up at “Demo HQ”, a cordoned area in the city centre where demolition material was sent and logged in the weeks after the quakes.

A person “involved in the processing of demolition materials’’, whose name was redacted, told him the dome had not turned up.

“Had it come through for processing he believes that it is the sort of thing that would have been brought to his attention,’’ Gunn wrote in his notes.

Boddy viewed about 6000 photographs of the scene. The photographs appear to have given him leads to follow. His notes show him trying to track down a “green vehicle and a red truck’’ as well as “a yellow vehicle near the scene.’’

Photographs of the scene show it swarming with diggers and trucks just one day after the earthquake.

Later images show men in orange overalls and breathing masks working to clear the site in early March. The mangled dome can still be seen in the background.

The photographs allowed Boddy to track the last known whereabouts of the dome. One showed it had already been crushed and pushed aside on the day of the quake. Another taken from a police helicopter on February 27 showed the mangled dome pushed up against two cars a little further down Lichfield St. Urban Search and Rescue photographs showed it remained there until at least March 2. They are the last known photographs of the dome.

Then on May 29, 2011, Mark Worner drove to hockey practice and saw the dome at the side of the road.

“The copper dome looked identical to the copper dome seen in pictures and TV footage lying upside down in the middle of Lichfield St near the High St intersection,’’ he wrote in his statement.

When he drove to hockey the next week it was gone.

Susan Tavinor, who has lived on the stretch of Momorangi Crescent where Worner saw the dome for 40 years, had no memory of such a dramatic object appearing on her street.

“I don’t remember seeing any copper dome,’’ she said.

In October, detective sergeant Mark Reid closed the case.

“Despite numerous enquiries to contractors working in the area no firm admitted to moving the pile of scrap metal that the dome was last seen sitting on,’’ he wrote.

‘’EQC and Civil Defence staff were also unable to assist police as they had insufficient records to show who was actually removing debris in the area of interest.’’

Reid contacted Bradley and told him the news.

“I told him that I understood that this wasn’t the news he wanted to hear, but there was simply no evidence to charge anyone.’’

While police may have concluded there was no evidence of criminal activity, people in the scrap industry or associated with the building believed the dome was crushed and sold for scrap.

One of the building’s owners at the time of the quake, Lisle Hood, felt certain it was stolen.

“It is a bloody shame and it is a bloody shame about a lot of things that happened in that period.’’

Former building owner, Andrew Hodge, agreed.

“That dome was thick, thick copper. You could have paid a fair chunk off your mortgage for that.”

Estimates vary over how much the dome may have been worth. A rough estimate based on the dome’s size and 2011 copper prices puts its value at about $7000.

But the dollar value was never its true worth. The dome embodied the city’s character, history and stories, from founding plans to Edwardian architects, and 1980s sex workers to fashion boutiques.

And then it plunged into the street and was stolen from us.

The rest of the rubble was cleared by early April 2011 and the corner site has been empty ever since.

But, even as an empty site, the corner is still emblematic of the Christchurch story - the slow recovery, the empty lots and the secrecy.

The neighbouring sites show the patchy progress of the Christchurch rebuild. The dilapidated buildings of Sol Square sit on the other side of Manchester St, while on the opposite corner a sleek new glass building gleams down High St. Across Lichfield St is a transitional project where children can play basketball.

The empty dome site is now owned by a company called Summitbuild Construction, whose director is Joseph O'Donnell. He declined to comment on his plans for the site when reached by telephone and asked that questions be sent by email.

Two days later he replied.

“Sorry for the late reply but I really can’t help you and would prefer not to go into any detail.’’

WORDS & VISUALS Charlie Gates

DESIGN & LAYOUT John Cowie

DIGITAL PRODUCTION Suyeon Son