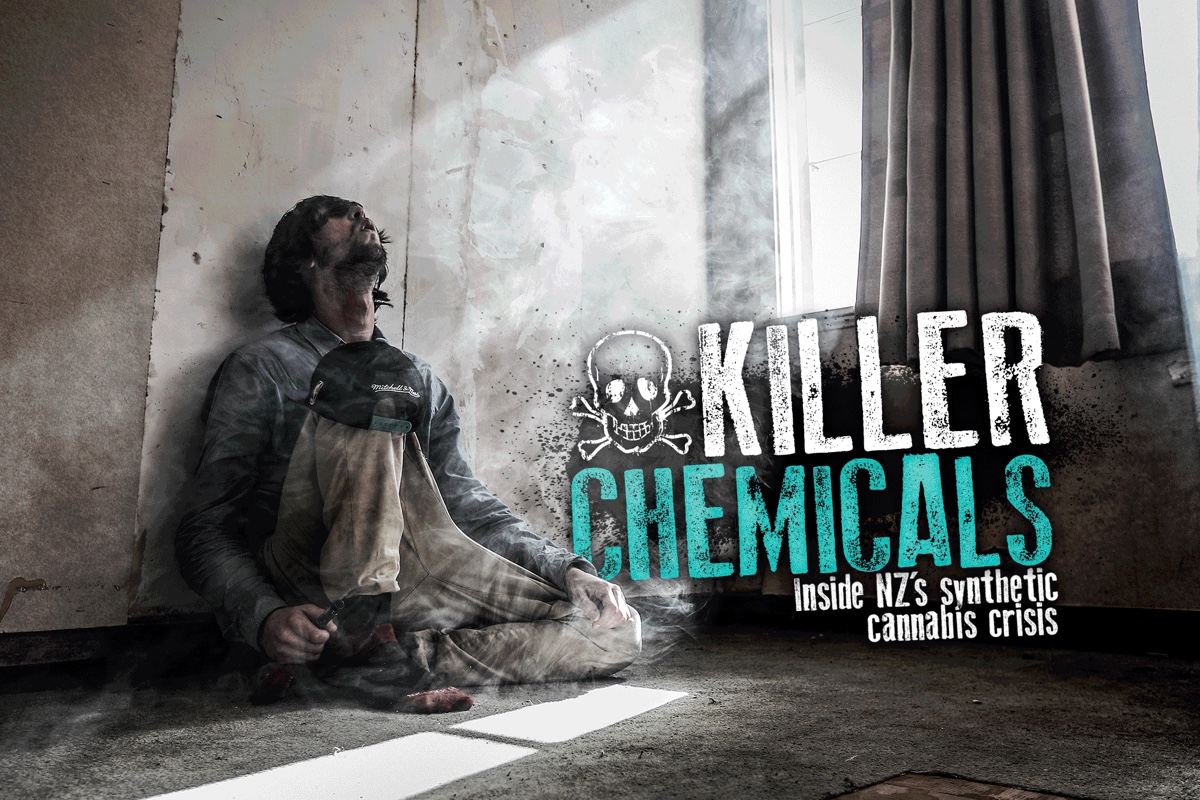

For a few weird months in 1991, Adam Dudding played piano for New Zealand’s most celebrated female impersonator. But when he went in search of memories of Diamond Lil, he found a strange, tragic tale of opera, filthy double entendres – and alleged sex crimes.

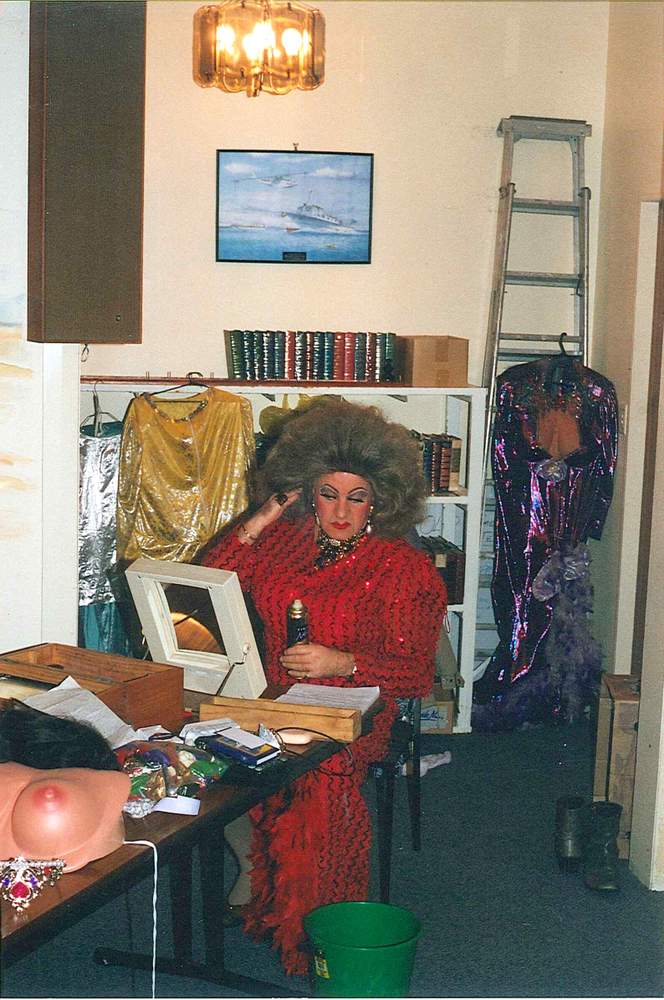

Marcus Craig adjusts his false eyelashes for the backstage transformation into the brassy, filthy-minded Diamond Lil. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

Twenty-six years ago, not long after I’d left home and moved into a Ponsonby flat with paisley wallpaper and mice in the kitchen, a musician friend asked me if I was interested in taking over one of his regular gigs – playing piano for a drag queen.

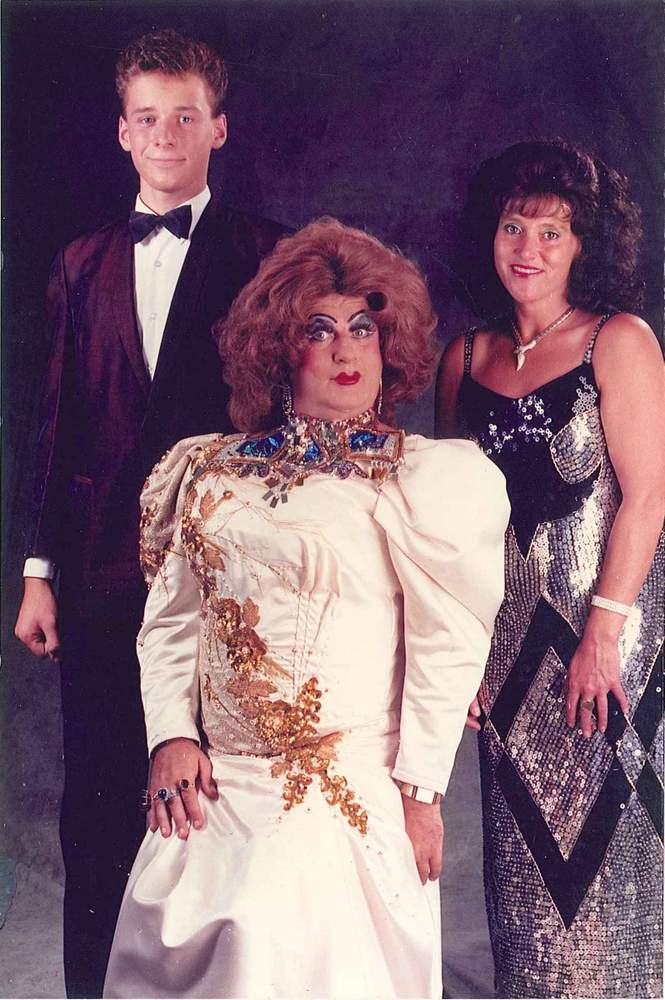

The drag queen’s stage name was Diamond Lil and his off-stage name was Marcus Craig. Both names rang a bell, but not very loudly. The friend set up an audition. The music was easy enough that I could muddle through, and my cover band’s gig calendar wasn’t exactly full. A few weeks later, armed with an electronic piano and some bass and drum sequences for backing, I became the one-man orchestra of The Diamond Lil Show.

Five months later, with little regret, I quit and got on a plane to London to begin my OE.

Marcus Craig as Diamond Lil, flanked by his touring stalwarts, singers Chris Powley and Valerie Rose. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

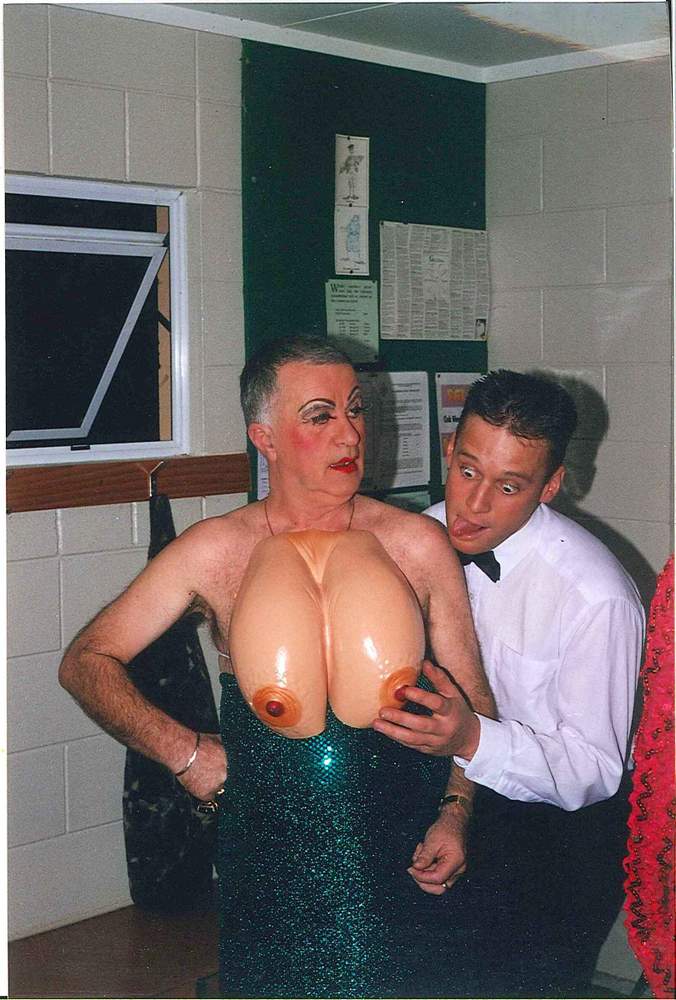

Lil’s 1991 Christmas card, featuring Chris and Marcus doing the mermaid sketch. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

Chris and seagull hat. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

The Diamond Lil Show was standup comedy with musical interludes, in which a man dressed as a balloon-boobed Mae West character delivered double (or single) entendres in a deep, gravelly drawl. Most of the jokes were based on the intrinsic hilariousness of the existence of sex, but these were leavened with brief forays into racism and the occasional rape or wife-beating gag.

Lil’s legs were superb and her costumes extraordinary – there were knicker-skimming mini-dresses and grand shiny frocks with plunging necklines, as well as fancy-dress versions of a Wild West harlot, a Queen Victoria, and a mermaid for which Marcus would waddle about in a tail and a vast pair of plastic comedy breasts.

There were up to eight costume changes per show, and while Lil tussled with her zips offstage, cabaret singers Valerie Rose and Chris Powley would entertain the audience with a repertoire that included It’s a Long Way to Tipperary, Country Roads, themes from The Muppets and Neighbours and, for the grand entrance, Hello Dolly (only they sang it “Hello Lilly”). That’s why they needed a pianist.

Back in the 1970s and ’80s, I was told, Marcus Craig had been seriously famous on the New Zealand cabaret scene. He’d been on TV, done Telethons, performed alongside Billy T James and Fred Dagg. And even though she wasn’t the household name she’d once been, Lil still had a loyal, mostly middle-aged audience all over the country.

Two or three nights a week Marcus, Valerie, Chris and I would play to packed Cosmopolitan Clubs and RSAs and Workingmen’s Clubs within striking distance of Auckland, and in December we toured the entire country, starting in Invercargill and working back north.

I was baffled by just about every aspect of the show, including why anyone would want to see it, but it was just one facet of an eventful year of new friends, flatmates, girlfriends, jobs and bands, and by the time I arrived at Heathrow, the memories were already starting to feel a little unreal – did that really happen?

After that, my Diamond Lil days barely crossed my mind, unless I was in one of those competitive pub conversations where you compare weird youthful jobs – “well I once played backing piano in a Timaru RSA for a female impersonator with a drink problem ...”

Then last year I published a memoir, which is mostly about my father but also partly about me. There’s a passage where I summarise all the half-interesting things that happened in my first 25 years: so alongside my stint as a double-glazing salesman and the time I had chicken pox but thought it might be syphilis, I expended precisely 17 words on my adventures with Diamond Lil.

A journalist interviewing me about the book said he remembered seeing Diamond Lil in the 1990s and asked me to expand on that a little. As I answered, memories started bubbling up. I remembered Marcus’s grumpiness on tour and my own resentment as the songs and jokes grew overfamiliar, and the time a performance was interrupted by an attack of Marcus’s kidney stones, and the time the tour van broke down.

But most of my memory was gaps. I knew I’d learnt the music for dozens of songs, but apart from the modified Hello Dolly I couldn’t summon the names of any of them. I knew I’d worked with two singers alongside Marcus, but I couldn’t remember Chris and Valerie’s names. I distinctly recalled that I’d soon been able to rattle off dozens of Marcus’s one-liners and dirty jokes, yet the only one I could remember was a fragment from a shaggy dog tale in which two people share a bed and lie back to back, “so they could put the wind up each other”. I’ve always enjoyed a good fart-related joke.

So I decided to see what more I could unearth. I couldn’t talk to Marcus – he died in 2013. But there were newspaper cuttings and YouTube clips and people who’d known him well. With luck there’d be enough in it for a newspaper article of my own. And my book had taught me that poking around in your own past can be surprisingly fun.

But what I learnt over the following year turned out darker than I’d expected. The story of Diamond Lil was one of opera, despair and sex crimes, of mince pies and a car crash and cops who looked the other way. And it was also a kind of accidental history of a particular moment in New Zealand culture, with cameo appearances from Howard Morrison, John Clarke and noted theatre-lover Sir Robert Muldoon.

Apart from a couple of extinct phone numbers for Marcus and Chris in a 1991 appointment diary, I had no personal paper trail to jog my memory: no photos with the crew, no sheet music, no diary entries, no posters.

I contacted my girlfriend of the time, Joelle, to ask if she could help me figure out some dates, and she Facebooked back saying she’d actually kept a diary that year, and on November 3, 1991, I’d given her a free ticket to The Diamond Lil Show at the East Coast Bays RSA in Browns Bay on the North Shore.

Her diary entry is mostly an account of the car that she’d recently bought for $25, and how it noisily expelled oil and pieces of engine just before the apex of the Harbour Bridge as we returned to the city, requiring a shove over the top from a friendly traffic cop, then a lift home. But there’s also a brief critique of the night’s performance.

“The show was dire – but the audience loved it. Adam sat behind the keyboard grinning (sometimes inanely) […] & I got bitched at by Marcus for not laughing enough.”

Joelle said she’d been struck by the audience “over-reacting to the sight of a guy in drag”, and that Marcus seemed to get increasingly angry as the night went on, “probably with me, since the only free seat had been near the front and I must have put him off his game”.

She thought the analogy with her clapped-out car limping along before dying a death “was appropriate for the way I felt about the show, but in retrospect that's very unfair. I think I was predisposed to dislike Marcus because you moaned a lot about how horrible he was to you, how demanding and diva.”

I’d forgotten about my moaning, but now she mentions it, that sounds about right.

The sole photographic proof of Adam Dudding’s 1991 stint as Diamond Lil’s pianist, taken at an unidentified venue. The one-man band is flanked by singers Chris Powley and Valerie Rose. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

Marcus Craig with a Diamond Lil cutout, posing for the Timaru Herald during a 1990s South Island tour. CREDIT: TIMARU HERALD/STUFF

My next source was the musician friend who’d gifted me the gig (he’s asked me not to name him in this piece). He played for Marcus for seven or so months, including a South Island tour. But where songs and jokes had slipped my mind, they’d lodged firmly in his, and when I rang him it all came out in a cathartic rush: the Muppets theme opening number; the mermaid sketch; the genie-in-a-lamp joke involving a thwarted wish for an enormous penis; another joke where Superman sees Wonderman spreadeagled in a room on the 110th floor of a skyscraper in “Metropolarse” and flies in to rape her only to get a shock when he finds the Invisible Man is already at it.

For days after we talked, he kept texting me gobbets of recovered memory:

“thanks to you I’m having Marcus Craig flashbacks ...

“Hello Dolly. One of his big numbers. Sung like the last gasps of a defective chainsaw …

“Pack up your troubles in your old kit bag and smile smile smile …

“How about: I don’t want to go to war mum. I don’t want a sabre up me Khyber! …

“This is so bad …

“I’ve buried this s... deep.”

Most usefully, though, he reminded me of the names of the rest of the troupe. Valerie Rose is probably still living on the Shore, he said. And Chris Powley would be easy to find because he’s performing all over the place: “He’s got a website.”

Pinning down an interview with Chris took a few months. He’s a busy guy, often abroad on ritzy cruise ships. He’s sick of the travel, but singing on the ships is “money for jam”, and where else would he get to play packed 1300-seaters with a ten-piece band every week? He’s in his 40s and has looked after his voice but reckons it won’t last forever, so he’s making hay while he can.

Chris was a core member of The Diamond Lil Show troupe for nine years and one of Marcus’s closest friends right until his death. At his home in Papakura, south Auckland, Chris had loads of old photos (including a blurry snap of me grinning inanely behind a keyboard) and a VHS of a Diamond Lil Show recorded in 1994 he could lend me. He also had Marcus’s awards and show posters and even some of the Diamond Lil dresses.

And this: in Chris’s patio garden there’s a potted pohutakawa, and in the soil beneath there’s a box holding Marcus’s ashes.

Marcus Craig was born David Charles Lennard in 1940 in Adelaide, Australia. According to a biographical sketch by the Variety Artists Club of New Zealand, his father was a railwayman who died in an accident when David was about six, and his mother was an actor who toured with a Brisbane opera company.

As a boy he sang and played piano and appeared in school plays, and as a teenager he worked in a music store before becoming an actor. He picked up theatre and TV roles and movie bit parts, including as a barman in the Mick Jagger movie Ned Kelly.

According to press interviews, around 1964 he married a woman called Penny, and they had a daughter Angela. Soon after that, Chris told me, Marcus discovered he was gay and they separated.

The VAC biography doesn’t note the timing of the name change, but by the time he arrived in Auckland in 1970 David Lennard was Marcus Craig. He appeared in Mercury and Central theatre productions and stole the show in a long-running Victorian Music Hall revue where his roles included “an unloved pantomime fairy, fat and fourtyish”, who “brought the house down”.

In 1975, with some nudging from impresario Phil Warren, he developed the character of Diamond Lil as the MC and central drawcard of Warren’s dinner-and-a-show cabaret the Ace of Clubs – “an allegedly sophisticated barn in Cook Street”, as John Clarke once described it, or the “Ace of Crabs” as Marcus usually called it. Very suddenly, at 35, Marcus and Lil became household names.

In interviews Marcus said the idea wasn’t to impersonate a female: Lil was a masculine, hairy-chested man unconvincingly pretending to be a “50-year-old mutton-dressed-as-lamb who simply adores sailors”. Lil was not, he insisted, a “drag queen”.

Whatever the definitions, audiences loved Lil. For season after season she played to packed houses at the Ace, alongside established and emerging stars. Scripts were by Doug Aston, musical arrangements by Carl Doy. There were double-bills with fellow luminaries Howard Morrison, Billy T James and Clarke’s Fred Dagg. Of the Dagg-Diamond double-bill, Clarke said later that “what Marcus most wanted to do was sing opera, so he’d get the drag schtick working and then repay himself with an aria”.

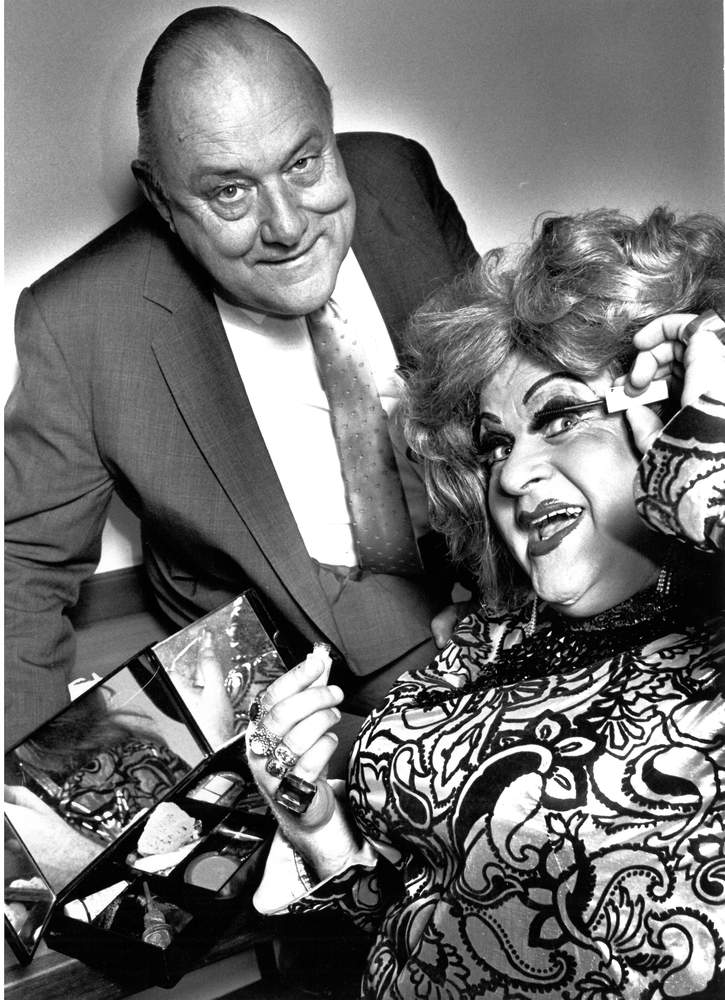

Diamond Lil with her big fan prime minister Robert Muldoon, at the height of her Ace of Clubs fame. CREDIT: GEORGE GREY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, AUCKLAND LIBRARIES

Telethon 1985: Lil gets a smooch from some guy from ‘Hill Street Blues’, as donors names run across the screen.

A live album of the Fred Dagg season was made, and the single Gumboots made the Top 20. Marcus shared his stage with Annie Whittle, Tina Cross, Ray Woolf, Rob Guest, Derek Payne, David McPhail and Jon Gadsby and visiting international stars. The VAC awarded him statuettes and scrolls. There was a TV comedy series. He did Telethons. Prime Minister Rob Muldoon was a fan. In 1979 Marcus told the Auckland Star “Mr and Mrs Muldoon have been several times. He has even asked my permission to use some of my jokes in his own speeches.”

Then In 1983, after 10 years and thousands of performances as Lil, Marcus left for Australia, saying he needed a break. He had a retail job at a sex shop in Kings Cross, Sydney, but intermittently dusted off the frocks for returns to New Zealand, including another Telethon and a wildly successful season at the Ace of Clubs in 1985, a last hurrrah before it was demolished to make way for the Aotea Centre.

With the Ace in rubble, the Diamond Lil show hit the road. By 1988 Marcus was based back in Auckland, and Valerie and Chris were the two permanent members of the touring show that I would stumble into three years later.

By popular demand: 1980s billboard for the Diamond Lil tour. CREDIT: VALERIE ROSE COLLECTION

Chris was 14 and a year off leaving school when he auditioned to be Diamond Lil’s singer in 1988. A child singing prodigy, he’d been in showbiz since 11, mentored by Lou Clauson of the 1960s comedy music duo Lou and Simon.

He remembers Marcus with affection but no illusions – there was the drinking, the sulking, the tantrums. There was the fast turnover of pianists: “I was always surprised with anyone who stayed longer than a week.”

Chris stuck with it because the pay was decent and he liked Marcus and he enjoyed the show, even if he was initially too innocent to get all the jokes, like when the doctor asks Lil how often she has sex and she replies “infrequently”, and the doctor says, “Is that one word or two?”

Chris never quite knew how much to believe of the stories Marcus told about his past. He claimed he was close friends with British comedian Dick Emery and John Inman from Are You Being Served?, and that he’d once sung with Luciano Pavarotti, who’d also been his flatmate.

There was an old vinyl disc with no label that Marcus used to play, of an impressive-sounding opera tenor, which Marcus said was a recording of himself. He told Chris he’d got cancer of the vocal cords in his late 20s “and that buggered his voice up and left him with that rough ‘’Ello dears how aaare ya’ sort of thing.”

All of these claims could be true, said Chris, but “Marcus was a bulls....er”.

Entertainer Chris Powley at his Auckland home, October 2017. CREDIT: DAVID WHITE/STUFF

Chris was looking very well. He’d filled out a bit from the rake-thin teenager I used to kill time with in a motel room in Timaru or Cambridge or Blenheim, but his voice – rich and smoky and with something of the vibrato of his idol Howard Morrison – was the same.

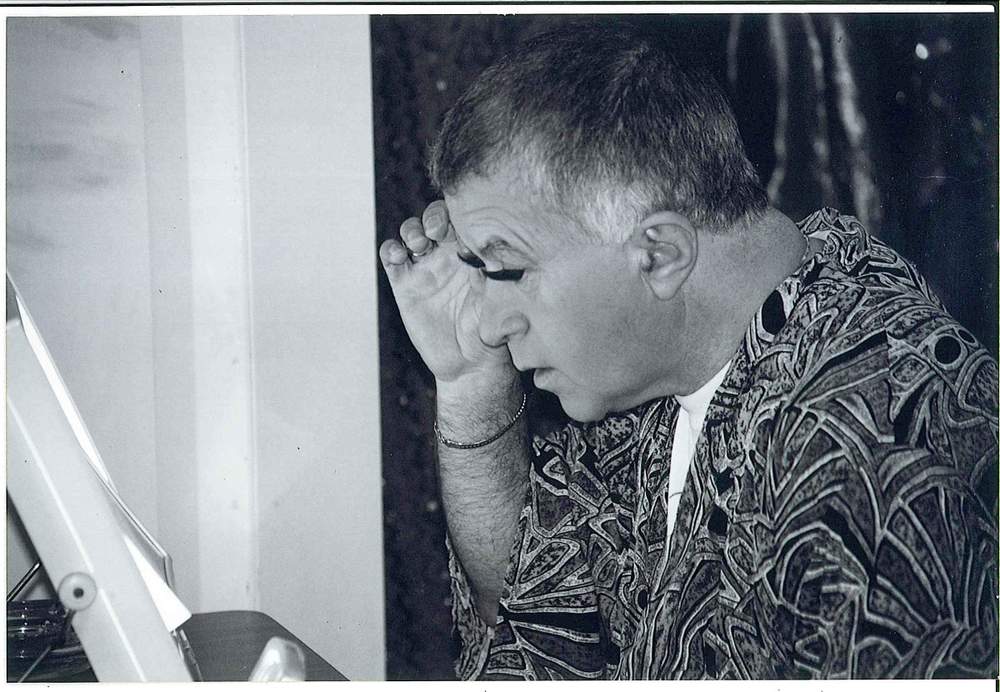

As he talked about life with Marcus, more of my own memories swam into focus. I remembered Marcus breaking into snatches of aria in a tuneful falsetto, or casually playing a difficult Mozart piano piece. I remembered that he used to wee into a bucket of water at half time and use the urine-enhanced water to wash his face before redoing his stage makeup, and that he liked crosswords and TV quiz shows, for which he always knew every answer. I remembered noticing that beneath his habitual glower Marcus was taking everything in.

I remembered squeezing into the white van with a trailer behind full of frocks and fake breasts, and Marcus at the wheel, driving atrociously. At every hill intersection he’d ride the clutch for minutes rather than use the handbrake, and you could smell and hear the van’s insides grinding toward extinction. (Valerie discovered years later that Marcus had never owned a driver’s licence.) I’d injured my lower back a couple of years earlier carrying speakers while in a short-lived rock band, so by the end of the day-long drives of our South Island leg I’d be in agony, and I remembered my fury when Marcus yelled at me to sit properly in my seat, rather than lying on the van’s floor.

I remembered walking around Invercargill with Chris, wondering what people did there. I remembered sitting in a beer-smelling RSA, bashing out the chords to Old MacDonald, which was always our most popular song.

I remembered laughing genuinely at Lil’s lip-smacking and groin-grinds and eye-rolls and wordplay and penis jokes the first time I witnessed them, then chuckling the second, then weakily smiling the third, and thereafter feeling acutely aware, as I perched behind my keyboard stand on the side of the stage, that the audience could see my face as it alternated between stony-faced boredom and a rictus of faked amusement.

Snapshots from the ad hoc dressing rooms of the touring Diamond Lil Show. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

Lil’s cheeky Queen Victoria dress always ended the first act, and always brought the house down. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

Before I started, my musician friend mentioned that Marcus had once been up in court charged with sex offences against an underage boy but he’d got off, and there had been doubts about the accuser’s claims. He’d also warned me that Marcus had an appetite for vodka, and could get through two bottles during a single show. Apparently it had little effect on his performance but after the final number he’d turn nasty and look for someone to argue with.

I was in fact spared the alcohol-related horrors, because in Petone a few weeks before I started, Marcus had collapsed to the floor mid-joke, bringing the performance to a halt. Chris took him to hospital where they said his kidneys were failing and if he didn’t stop drinking he’d die. From that day on, said Chris, Marcus laid off the vodka, “though he’d still have the odd glass of wine”.

Chris said Marcus always insisted on driving the van after gigs no matter how drunk, and if he was pulled over while weaving down the road, which happened more than once, he’d turn on the Diamond Lil charm for the cops – “’Ello mates – ’ow are ya?” – and be sent on his way.

“There were times we shouldn’t have made it home. He rolled the car once, drunk, and still had his pie in his hand at the end. He’d always say ‘Don’t eat McDonald’s, don’t eat pies and all that crap’, but after a gig when he was drunk he’d always have a pie or McDonald’s in his hand. And the next day he’d deny eating it.”

Marcus drunk could be a “nasty, horrible man”. Once, after Chris’s parents came to a show at the Lower Hutt Cossie Club, Marcus started badmouthing them.

“He disagreed with the way they were raising me with so much freedom. He thought they should be putting me into some sort of a vocal school. After they left he decided to tell me exactly what he thought, in a vulgar manner: ‘Your mother needs a good slap in the —, a good kick in the —, you know.

“I bailed him up against the wall and told him to pretty much f... off and get out of my life.”

By morning Marcus had forgotten all about it, and was mystified when Valerie told him Chris had gone home to Auckland mid-tour. There were a couple more similar bust-ups over the years, and each time Marcus would grovel and Chris would come back.

“Because he had this beautiful side to him – a heart of gold. He’d give you the shirt off his back to help you. But then he could turn – a Jekyll and Hyde sort of thing. He was a joy to work with after he stopped drinking.”

Vodka-infused or not, Marcus’s kidneys still weren’t in great shape when I joined the show. At half time of a gig in Mt Maunganui he suddenly lay on the floor and started groaning. A doctor was summoned to give him an injection for what I now presume was kidney stones, and Chris, Valerie and I treated the audience to some extra songs to kill time until Marcus lurched back onstage to thunderous applause.

* In fairness to the gag-writer, here’s the rest of that joke “… He said, ‘Firstly Madam, I’m not a sarbender, I’m a bartender. Secondly dear, you don’t want a Marconi, perhaps a martini? Thirdly love, you haven’t got heartburn – your left tit’s in the ashtray.’”

Chris Powley and Valerie Rose recall the highlights of working with Marcus Craig. CREDIT: DAVID WHITE/CHRIS MCKEEN/STUFF

When I quit in early 1992, The Diamond Lil Show already felt like it was near the end: a slowly closing window into the pinch-minded popular culture of 1970s New Zealand, performed by an ailing, unhappy old man (Marcus was in fact only 52 – but I was only 21 so forgive me.) Yet the show kept touring steadily for another two years, and there were occasional reunion tours for almost a decade after that.

The regular tours ended because Marcus’s other permanent singer, Valerie Rose, had a baby daughter and grew sick of Marcus’s lack of consideration. The last straw was after a Rotorua gig where she didn’t get back through her own front door on the North Shore till 4am, breasts leaking milk, to a hungry baby. She pulled the plug and Marcus didn’t have the heart to start from scratch with a new singer. He returned to Australia once more, and it remained his base for the rest of his life.

I visited Valerie in Browns Bay, where she lives with her husband and daughter and runs a dog-grooming company called Barking Mad. Born in London, Valerie came to New Zealand as a teenager, She first met Marcus when he and Billy T James were judges on one of the many TV talent quests she entered in the 1970s.

“I always remember Billy T saying ‘You exude a warmth that’s outstanding’, and Marcus said, ‘Ooh, you picked a difficult song, but I love the dress.’”

When she auditioned for Marcus’s post-Ace of Clubs touring troupe in 1985 he remembered her – “I loved your dress!” – and she was given a week to learn a two-hour show. In all, she worked with Marcus for 15 years, though for much of that time she also had a well-paid day-job with Telecom.

Retired cabaret singer Valerie Rose now runs a dog-grooming parlour from her home in Browns Bay, Auckland. CREDIT: CHRIS MCKEEN/STUFF

Valerie and Marcus, in the early days of the Diamond Lil tours. CREDIT: VALERIE ROSE COLLECTION

Like Chris, Valerie had fond memories of a flawed friend – someone who was ferociously bright, often kind, and generous with money. Someone with real musical talent and superb comic timing. Someone who could be self-absorbed and grouchy when sober, and vile when drunk.

Marcus could organise a show, said Valerie, but he was clueless about business and reckless with money. He accumulated no wealth despite those years at the Ace of Clubs. In the early 90s his phone was cut off for non-payment, and when she visited his Beach Haven rental she found empty cupboards and more upaid bills. She stocked the pantry, paid his debts and told him to pull himself together.

She reminded me that when Marcus’s van broke down when I was with them in Gore (as I remember it, the much-abused clutch finally quit), she bailed him out once more.

“He didn’t have any money, so Chris and I bought a van, because it was the only way we could get home. It was about six grand, and he paid me off $20 extra per gig.”

For all that, though, working with Marcus was great fun, especially on-stage. He’d veer off-script and they’d have to scramble to keep up. Like the time when Valerie was visibly pregnant and they were doing the “outer space” sketch set amid the rings of Saturn.

“One of my lines was ‘Something was in the air that night ...’ And Marcus turned around and said, ‘Yes – look at you – your legs!’ And all of a sudden the whole sketch started changing.”

Offstage he could surprise in less pleasant ways. Like when they were in Waitangi and decided to take the touristic Cream Trip island cruise on a day off. The boat was about to cast off when Marcus suddenly scuttled ashore. When they got back he was sitting by the hotel pool, red as a lobster. When Valerie asked why he’d jumped ship, “he said, ‘I’m not getting on that boat with all those bloody chinks. Bloody slant-eyed bastards.’”

She wondered if the spasm of xenophobia was actually a cover for Marcus’s sudden urge for a drink, “but it was really quite …” She tailed off. Actually, she added, he was pretty racist about Polynesians too.

Marcus’s misanthropy was a broad church.

“He had a little hate for women going on,” said Chris. “He’d make an example of women who yelled out in the show and say ‘You’re the reason there are so many gay men in the world.’”

Marcus was openly and comfortably gay, said Chris, with gay friends and some long-term relationships in New Zealand and Australia. Yet he would sneer about what he’d call “lispy” gays. He preferred those “where it wasn’t easy to tell”.

Valerie remembered playing a couple of gay clubs in Wellington, “but I don’t think Marcus felt in his comfort zone. They wanted us to come back but he wasn’t interested.”

Marcus wouldn’t have been seen dead near a gay pride event, she said, “and he hated queens – the ones that portray themselves as women and walk along K Rd. He didn’t like people dressing up as a female if they weren’t female.

“He was,” said Valerie, “a complicated man.”

Before meeting Chris and Valerie, I visited Auckland Public Library and copied all the Marcus Craig newspaper cuttings I could find. There were enthusiastic reviews of his Ace of Clubs shows and profiles of the rising 1970s star. His departures and returns from Australia were logged in celebrity gossip columns, and there was a lovely interview by Terry Snow where he dragged Marcus away from the double entendres to talk seriously about his love and knowledge of opera.

One short article from 1991 plugged a charity matinee at the Aotea Centre that I’d played and totally forgotten about. We played a short set alongside many others, including Australian Barry Crocker, singer of the original Neighbours theme. Crocker impressed me backstage by telling me the Neighbours royalties still earnt him $100 beer money a week, and he showed me how his autograph contained a caricature of his own face – a trick he’d been taught by Rolf Harris.

As I’d hoped, the library also had cuttings about Marcus’s sexual assault trial of 1988, the case my musician friend had mentioned.

The Auckland Star reported that a jury at Auckland High Court had found Marcus not guilty of three indecency charges – assault with intent to commit sexual violation, unlawful sexual connection, and indecent assault on a 14-year-old boy, one afternoon at Marcus’s Beach Haven home.

The defence successfully argued that “Craig would have had little or no time between a hairdresser’s appointment in Papakura that afternoon and a television rehearsal later to commit the alleged indecencies”, and suggested that the boy, who had previously done odd jobs around his home, had made up the allegations because Marcus had caught him stealing.

Make of that what you will.

What I hadn’t expected to find, though, was another set of clippings from 1977, at which time Marcus was really at the peak of his fame. According to the Star, the Herald and the Saturday sports tabloid 8 O’Clock, Marcus had faced an uncannily similar set of sexual assault charges 11 years before the case I already half-knew about.

He stood trial at the Supreme Court in Auckland accused of two charges – performing an indecent act on a 13-year-old boy and allowing the youth to perform an indecent act on him. In evidence, Marcus said he had never seen the boy before and described the allegations made against him as “filthy lies”.

Yet Marcus’s defence had one enormous hurdle to overcome: when police first put the accusations to him, he had given a signed statement admitting he had indeed behaved indecently with a “youngish” chap he met in the city and took to his Mt Eden home.

That’s where things get truly bizarre. I’ll quote from the Herald report of Marcus’s court evidence:

When he made his statement to Mr Farrant, he said, he was in a state of mental and physical exhaustion. He had been working up to 80 hours a week before the interview, in addition to taking part in the Telethon appeal two days earlier.

He said he was horrified when told of the accusations but did not think, because of his theatrical work, that he would be believed if he denied them.

“I said yes to everything to get out of the police station,” he said.

“I suppose I basically became Diamond Lil for a while. I was just acting. I just wanted to get out of there.”

Craig said he saw his statement again several days later and was “shattered”.

Craig’s doctor, Dr R.A. Roche, said he believed there were times when Craig was acting without knowing it.

Another report said Marcus had taken two Valium tablets before going to the police station and was “completely and utterly exhausted both mentally and physically”.

On October 13 1977 the Herald report of the verdict records that in his summing up “Mr Justice Bain said he had to warn the jury that in sexual cases it was dangerous to act on the uncorroborated evidence of the person on whom it was alleged the indecency had been perpetrated”. It noted that “Mr Justice Bain said the youth was capable of some untruths.”

The jury of six women and six men took nearly five hours to reach a verdict: not guilty on both charges.

Newspaper cuttings from Marcus Craig’s 1977 trial at the Supreme Court in Auckland, on charges of indecent assault of a 13-year-old boy.

Based on nothing more than these news cuttings, which tell us a famous entertainer walked free after claiming an initial written confession of child sexual assault was in fact a piece of accidental cabaret, you have to consider the possibility that Marcus was in fact guilty as hell. Given the five-hour deliberation, you have to presume some of the jury had similar feelings.

Then add the knowledge that a decade later Marcus would face near-identical charges concerning a boy of similar age. Think, too, about the status of Marcus Craig in 1977 – photos with the prime minister; Telethon appearances; a hit cabaret show. Think of that warning to the jury about the dangers of uncorroborated abuse claims.

Think, perhaps, about a much more recent case – the permanent name suppression granted to a “leading New Zealand entertainer” who had pleaded guilty to indecently assaulting a 16-year-old girl in 2009.

Think about what we’ve learnt about Rolf Harris and Jimmy Saville and Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey, and how blind eyes are turned on the predatory behaviour of famous men.

Listen to the familiar ring of this quote from Marcus’s employer Phil Warren after Marcus’s 1977 not-guilty verdict, when he told 8 O’Clock that in his 25 years in the entertainment industry he had many times heard of public names having allegations made against them.

“It happens to entertainers, politicians and anyone in the public eye.” Warren said. “I haven’t escaped myself. I am aware that some impressionable people fantasise…”

If you start to suspect that one or both of the allegations against Marcus were true, you also have to wonder if they were isolated incidents or not.

What should we make of a 1987 interview where Marcus talked about his time at the Pleasure Chest sex shop in Kings Cross, and how affected he’d been by the streetkids he met at the Cross, who were “into drugs and sex even at their age and the results were horrifying”.

Moved by their plight, he’d helped them as a counsellor via a local Christian charity: “I know I saved a few of them – but you always remember the failures, the ones who have died out there.”

Is this true, or was Marcus acting again for the benefit of the journalist?

I asked both Chris and Valerie what they knew about the court cases.

At the time of the 1988 trial Chris had accepted Marcus’s protestations that it was a false accusation, especially seeing the logistics of it meant the offending couldn’t have happened when the boy said it had. He knew nothing about the 1977 trial – after all, he was three at the time – but when I spelt out the flimsy-sounding defence, and asked if he thought Marcus could have been guilty, he said: “It wouldn’t surprise me. Because he liked young guys.”

Chris never knew of, nor suspected, anything involving anyone underage. But in Australia, in his 60s, Marcus had a really serious relationship with a guy in his early 20s.

Chris himself was 14 when he joined The Diamond Lil Show. Did Marcus ever hit on him?

“No,” said Chris. “I was travelling to Australia by myself at 11. I was super-confident and knew who I was. I think he was too wise to make any advance towards me.”

Valerie too knew nothing about the 1977 trial, but at the time of the 1988 trial she asked Marcus directly if he was guilty.

“I said, ‘Look Marcus. It’s got nothing to do with me, apart from the fact that if you get put inside I’m out of a job. Your sexual preferences have nothing to do with me – but did you? Because there’s no smoke without fire.’

“And he said, ‘There shouldn’t be any smoke.’

“He never said yes, he never said no, he just turned around and said, “There isn’t any smoke.”

The show’s opening number, “Well Hello Lilly”, as captured in a 1994 video recording.

CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

When I watched Chris’s video of a 1994 Diamond Lil Show I recognised all the songs and jokes. They hadn’t changed since I was on the piano. They never, ever changed.

The Ace of Clubs scripts – mostly by Doug Aston but with borrowings from the likes of Dick Emery and Danny La Rue – were recycled for decades. Marcus was a nimble ad-libber, but he had no interest in updating his material.

Valerie: “He said why fix what’s not broken, but I think it was because he wasn’t actually the writer. After he left the Ace he stagnated.”

Chris: “When Phil Warren said to Marcus I want you to jump into a dress and tell jokes, Marcus was like, forget it, that’s not me, I wanna be a singer. But when he saw how successful it was, and how much money it brought in, he thought oh, it can’t be all that bad and continued it. And leant on it. And then depended on it.

“There was a lot of deep-rooted anger there. He was successful but not by being who he wanted to be. Being the character of Diamond Lil – he hated it. He succumbed to the fact that that was all he had, and that was all he was going to have. There were no efforts from him to be anything other, not even to get new jokes.”

After leaving for Australia in 1994, Marcus never lived permanently in New Zealand again, despite the intermittent revivals. Neither Chris nor Valerie could understand why he stayed in Australia, given that all his friends and career and successes were here.

He lived in Sydney then Brisbane then the Sunshine Coast. For a time he worked at a Brisbane record store where he was the opera expert, and that led to an unpaid spot on a community access classical station in Brisbane, where twice a week he’d rave brilliantly about opera and play his favourites.

Even after all the gigs ended, Chris and Valerie stayed in touch, and both said Marcus seemed sad.

“I always phoned him on his birthday,” said Valerie, “and it was always, ‘Oh you remembered!’ You could tell he was getting old, and probably down in the dumps and fed up.”

Chris would always visit if his work took him to Australia. A few months before Christmas 2012 he rang Marcus.

“He was talking about dying: ‘I don’t have much to live for any more, and I just want to die.’”

Chris invited him over to Auckland for Christmas, offering the fare when Marcus said he couldn’t afford it, but then had to cancel when a cruise ship gig was extended over Christmas.

“I felt a bit stink about it. I had to ring up Marcus and say, ‘I’m not going to be home, sorry mate.’ It wasn’t long after that that he died.”

On August 10 2013, the diabetic, lifelong smoker and one-time hard-drinker had a massive coughing fit while in front of the TV in his flat, burst a blood vessel in his lungs and drowned in his own blood. He was 73.

When Marcus didn’t turn up for a regular Sunday coffee, a neighbour found the body. There was no next of kin to be found, but Chris’s number was the most frequently dialled in Marcus’s phone.

Chris flew to the Sunshine Coast to tidy up his affairs. He looked around Marcus’s tiny pensioner flat and thought “How did you end up here? How did you go from being where you were in New Zealand to being in this little four-by-three death cabin?”

Marcus had no money, no real assets. All his things had already gone to a charity shop, including a large collection of opera records.

“I was gutted, because there were things I’d have liked to have had, like a jewellery box that I made out of timber at school for Marcus, and a ruby ring that Danny La Rue gave him, that he treasured.”

Chris placed newspaper ads seeking family members, but no one responded so he arranged the cremation, hid the ashes in his suitcase and brought Marcus back to New Zealand, his second and true home. He and the Variety Artists Club organised a memorial at The Bays Club in Browns Bay, a frequent Diamond Lil venue. Valerie sang Thank You For Being A Friend.

The final years: Chris with Marcus in Australia a few years before his death. CREDIT: CHRIS POWLEY COLLECTION

Irang the Brisbane community radio station where Marcus had a weekly opera show until 2009.

General manager Gary Thorpe said he first knew Marcus as the opera expert at a city record store who would make extremely assertive recommendations about which CDs 4MBS Classic FM should review next. He’d also bump into Marcus at the opera.

Eventually, Thorpe invited Marcus to share his strong views and deep knowledge with his listeners. Marcus was cautious but once behind the microphone “he was a natural”.

“He was a very entertaining broadcaster. He was genuine in his enthusiasm, and very scathing about the singers he didn’t feel could do it, but in a way where you couldn’t take offence. It came from a deep love of the artform.”

Later, Thorpe saw Marcus was struggling but proud. His journey to the studio involved three buses, and when failing health made that impractical Thorpe offered to pay for a cab each time, but Marcus refused, saying he didn’t want to put anyone out.

Thorpe had no inkling whatsoever of Marcus’s former life and New Zealand fame. But there was this one thing Marcus would do occasionally that would mystify him.

He’d be talking to Marcus, especially in the record store, “and Marcus would fall back into a character, firing off a caustic remark about a singer, but I never knew what that character was”.

Then when Thorpe went to the wake in Australia, there was a screen playing clips of Marcus in a series of bright frocks, stalking the stage and grinding out the smutty jokes.

Thorpe was stunned to realise that his opera friend Marcus had once been a performer, a drag queen no less, and that the flamboyant, deep-voiced character who would occasionally take possession of Marcus when they were chatting in a Brisbane record shop actually had a name: Diamond Lil.

*Adam Dudding’s memoir My Father’s Island ($35) is published by Victoria University Press.