At least 20 people have died after smoking synthetic cannabis, but where is the community outrage and Government action plan?

In part two of our series we speak to a grieving mum, and a former dealer who was with her son shortly before he died.

The last time Stephanie Harawira saw her stepson alive, he was off to smoke synthetic cannabis.

She was in central Henderson, West Auckland on June 13 when she spotted, Kahu James Harawira, who'd been living rough, and another man she knew, Robert Marriner, a known synthetics dealer, meeting in the street.

"I challenged them about smoking that rubbish...Robert just stood there and justified it - 'oh no Steph, it's all right'.

"They weren't getting it - all they knew is they were going off to get wasted. Within 24 hours my boy was dead."

Kahu James Harawira, whose father, Tai, is politician Hone Harawira's brother, died just a few days past his 29th birthday. The interim cause of death has been given as heart failure; coroner's inquiries are continuing.

His family believe synthetics killed him. Hone Harawira, who as leader of the Mana party has taken a hard line on drugs, says his nephew’s death is still too raw for him to talk about.

Kahu James Harawira was known as Joy growing up, because he was such a delight.

Harawira is one of at least 10 people to have died in Auckland after smoking synthetic cannabis - known on the street as "synnies" - between June and August.

Many of the victims were, like Harawira, from the vulnerable margins of society - homeless, mentally ill, unemployed - often all of the above.

And we've discovered the recent deaths were not the first - last year Hamilton man Toa Tuau - also under mental health care - collapsed and died after smoking the drug with friends. In total, at least 20 deaths are before the coroner.

Stephanie Harawira is an award-winning community worker whose Ezekiel33 Trust helps young people and families.

She'd watched as synthetics cut a swathe through the community - creating a "darkness" she'd not seen before - and was one of the leaders of a nationwide movement to ban the products.

Eventually that pressure forced the Government to revoke interim approvals under the Psychoactive Substances Act, removing all products from sale in 2014.

But Harawira was powerless to stop her stepson, whom she’d raised since age 5 and considered her own, from heading down his fatal path.

She has no doubt who she blames for his death - Peter Dunne and the politicians she believes created a market for synthetics by allowing them to be sold legally for too long.

Harawira used to run a drop-in centre for youth in the Henderson CBD and it was behind this building that Kahu, the fourth eldest of her 11 children, was found dead.

His bank statements showed he'd made a couple of small purchases - probably papers - from the nearby Shosha store, which did a roaring trade in party pills and synthetic cannabis when they were legal.

Harawira had been using synthetics for at least three or four years.

He'd only recently returned home after a decade in and out of mental health facilities.

When he was little, his nickname was Joy, because he was such a delight to have around, but that changed when he turned 18 and tried methamphetamine.

"Something in him broke when he started down the drug scene,"

"Something chemically imbalanced that boy - he was never the same.

"We lost him into the mental health system for about 10 years."

She says he was fit, strong and healthy when he went into care.

"When he came back to the family he was overweight, obese and on loads of pills."

When he tried synthetic cannabis, he quickly became "locked in, hungry for it.

"He used it as often as he could. Every Tuesday was his payday, we knew he'd be off with his friends. Wednesday to Saturday he was at the highest risk, the rest of the time he'd be broke and they'd be peddling for money."

It had a horrible effect on Kahu. "You just couldn't talk to him, he was in la-la land. All we could do was love him and try and call him home for a feed and a shower."

Harawira had only been home about a month when he suddenly announced he was going to live on the streets.

Stephanie and Tai would drive around Henderson to see if they could find him and get him home for a meal.

On the day he died, he was heading to Waitemata Community Law Centre.

"We were helping him out with some other issues," says manager Tom Harris. "He came down to see me...I wasn't here.

"He must have been holding, he walked around the back and had a smoke, that's where he passed away."

Harawira was found in a covered carpark, a popular spot for drug users and the homeless - his friends have burned his name into the concrete slab roof as a memorial.

It's the same place where staff once found a heavily pregnant young woman performing a sex act on a man in exchange for a bag of synnies.

After he died, Stephanie wanted to track down Marriner and ask him where the drugs came from, "but we knew it would have got out of hand because we were so emotionally charged".

We went looking for Marriner and found him at his flat under a rickety house in Henderson, which he found through a programme for the homeless.

It's sparse, but for a man who lived rough for 33 years, it's a palace. This is where he and Harawira smoked synthetics the day before Harawira died.

Marriner's homeless friends often stay over, and they'll sit around smoking synnies, "having a giggle".

As we arrive, two young homeless men are leaving - according to Marriner they have synnies on them; one is off to court.

Marriner, his face and body covered in tattoos, munches on toast as he matter-of-factly talks about his previous life of drug dealing.

He admits police have "hounded" him about whether he supplied the drugs which Harawira took before his death.

He says he didn't - that his mate had his own and went elsewhere for a re-supply the day he died.

"Like I said to them, 'if you've got proof then come and arrest me, if you haven't, then just leave me alone'."

Police won’t say if they are investigating Marriner but on Friday announced they had arrested three men, aged 22, 30 and 33 for supplying the drugs involved in two West Auckland deaths.

Marriner, 54, makes no secret of the fact that after psychoactive substances were banned, he would buy, sell and distribute them.

It was a "beautiful" time, he says, because he was making thousands of dollars and was debt-free.

"The stuff I was getting was from the shops, Kronic. When they made it illegal there were containers and containers of the s... around here bro. It was quite easy to get hold of."

And there was no shortage of demand.

"You walk down the road, you go past five kids...there's about $100 at $20 each.

He wouldn't sell to anyone under 18, he says.

"Do I regret any of that? No I don't. If it wasn't me it would have been someone else."

He says he no longer sells synthetics, but still smokes them.

There's nothing wrong with it, he says, it's the added "poisons" that are killing people.

"No-one knows what's in it unless you're the person that's making it.

"There's all sorts of things you hear that's been put into it, nobody really knows. Some people say it's 1080, acetone's been [mentioned]."

Synthetics are cheaper than natural cannabis, he says, and provide a far more intense high.

"You'd have to smoke about eight or nine joints to get that one hit you get off one puff of synthetics."

For homeless people, most of them mentally ill and struggling to be heard, the drug takes them away from their problems.

"It takes you to a place where you don't have to think any more...you don't have to be yourself any more.

"No-one talks to you, no-one understands you, so what's the point?

"You might as well just walk around like a zombie for the rest of the day."

He knows two other homeless synthetics users who've died. One, Bomz, was found dead on the steps of a church in Manurewa.

The deaths are sad, Marriner says, "but it's like all drugs, you take too much of it...you're responsible for yourself.

"I feel sorry for those ones that have died, but look at us ones that are still alive, still smoking the stuff.

"I think every drug does damage, but it's about educating ourselves on it.

"How can you deal with something you don't know about?

"At least P and alcohol have got counsellors. Where's the counsellors for synthetic smokers, the programmes, where's the place where people can go for help?"

Lawyer Tom Harris says synthetics have caused chaos in the community.

Harris, whose law centre helps a lot of West Auckland's homeless, says he's watched over the years as synthetics users have slowly faded away.

"I believe this is a health issue, you're not going to get rid of this by being punitive and arresting addicts."

Politicians ignored community concerns about synthetics for too long, he says.

"It dropped in our community like a bomb.

Overnight this place goes wild, people losing the plot.

"There was a full blown street rumble between two gangs who wanted to take control of Shosa.

"By the time they figured out how harmful it was it was too late, the addiction had already kicked in for many people and they were queuing up in lines outside the stores, committing petty theft, crime, prostitution.

"Then when we tried to tell the policy writers 'look what's happening', they had already hunkered down and said 'oh no, through regulation we're going to take care of this', and they didn't."

The deaths we're seeing today are a result of long-term use, he says.

"Now we're four years down the track we're seeing the...health issues, rates of heart attacks in young men. That's the pattern - they're dying of heart failure.

"We're in the middle of it - I believe we're yet to get to the end."

Harawira believes Dunne, the associate health minister who ushered in the Psychoactive Substances Act, has "blood on his hands" for trying to regulate drugs that should have been completely banned from the start.

She doesn't buy Dunne's argument that the crisis we have now is because the current ban pushed the industry underground.

"It was worse while it was 'out' because...your kids could sit there and smoke this stuff, and there was nothing you could do."

We caught up with Dunne in his office in Bowen House opposite Parliament, in his final days as an MP.

He's standing down at the election and the failure to get the Psychoactive Substances Act working properly is his biggest frustration.

He says politicians bowed to pressure in election year in 2014, even though by that stage the number of legal products had been reduced from over 300 to 41, and the number of regulated stores from over 4000 to about 150.

"Those people didn't need to die. That's an awful tragedy, there's no way you can escape that," he says.

"I think there needed to be less political grandstanding as there was from all sides, who were leaping on the clamour of what they saw as a big public health issue.

"But they didn't understand the consequences of their actions. Unfortunately these deaths have come home to roost."

He says a number of "myths" about psychoactives need to be debunked.

"The biggest myth of all is that I somehow introduced them to the market.

"They'd been around since the mid 1990s and by 2009-10 they were being widely sold in dairies...without any controls on them whatsoever.

"I'm the only person who has done anything to try and bring it under control."

He still thinks the Act can be resurrected, if an alternative for animal testing can be found.

"I've been pushing the scientists, there must be alternatives. I'm not satisfied that nearly five years down the track we're yet to come up with those.

"I think the regulated market is still the way to go because that gives you some control.

"I'll be keeping a watchful eye on it...defending my legacy because...I've not seen in any country an alternative that's better."

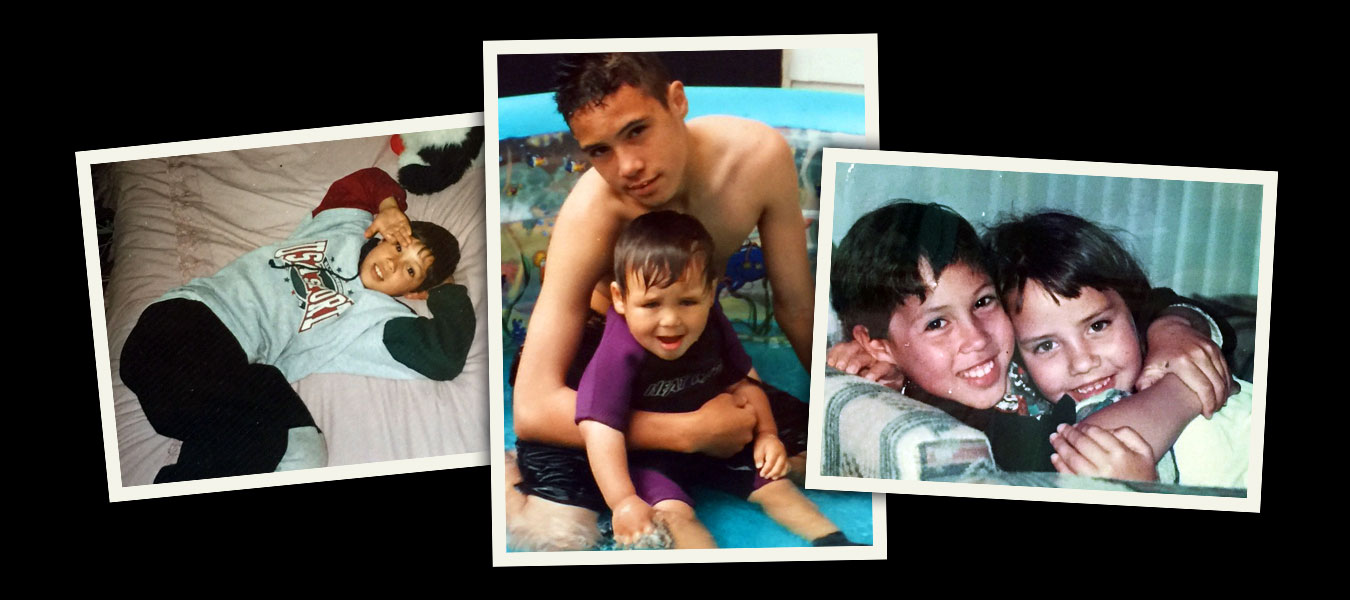

Kahu, far right, with his mum and some of his 10 siblings.

Stephanie Harawira scoffs at that. "I don't believe there is any such thing as 'safe' synthetics," she says. "They all need to be banned."

She has joined the board of Wild Side Charitable Trust, which connects addicts to treatment services, and wants to see the Government invest more in such organisations.

"What the Government is doing is not working. They need to recognise it's a problem and invest more money in centres around New Zealand where people can go and get the help they need.

"My boy's death makes me even more determined to fight this fight with synthetics. The sooner we rid our country from it the better."

Where to get help:

Alcohol Drug Helpline - 0800 787 797

Community Alcohol & Drug Services (CADS) - www.cads.org.nz

Wildside Trust - www.wildsidetrust.org

CareNZ - www.carenz.co.nz

Drughelp - www.drughelp.org.nz

Narcotics Anonymous - www.nzna.org

Salvation Army - 0800 53 00 00

Words

Tony Wall and Helen King

Further reporting

Michelle Duff

Visuals

Chris Skelton and Kevin Stent

Editor

Tony Wall

Producer/designer

Aaron Wood