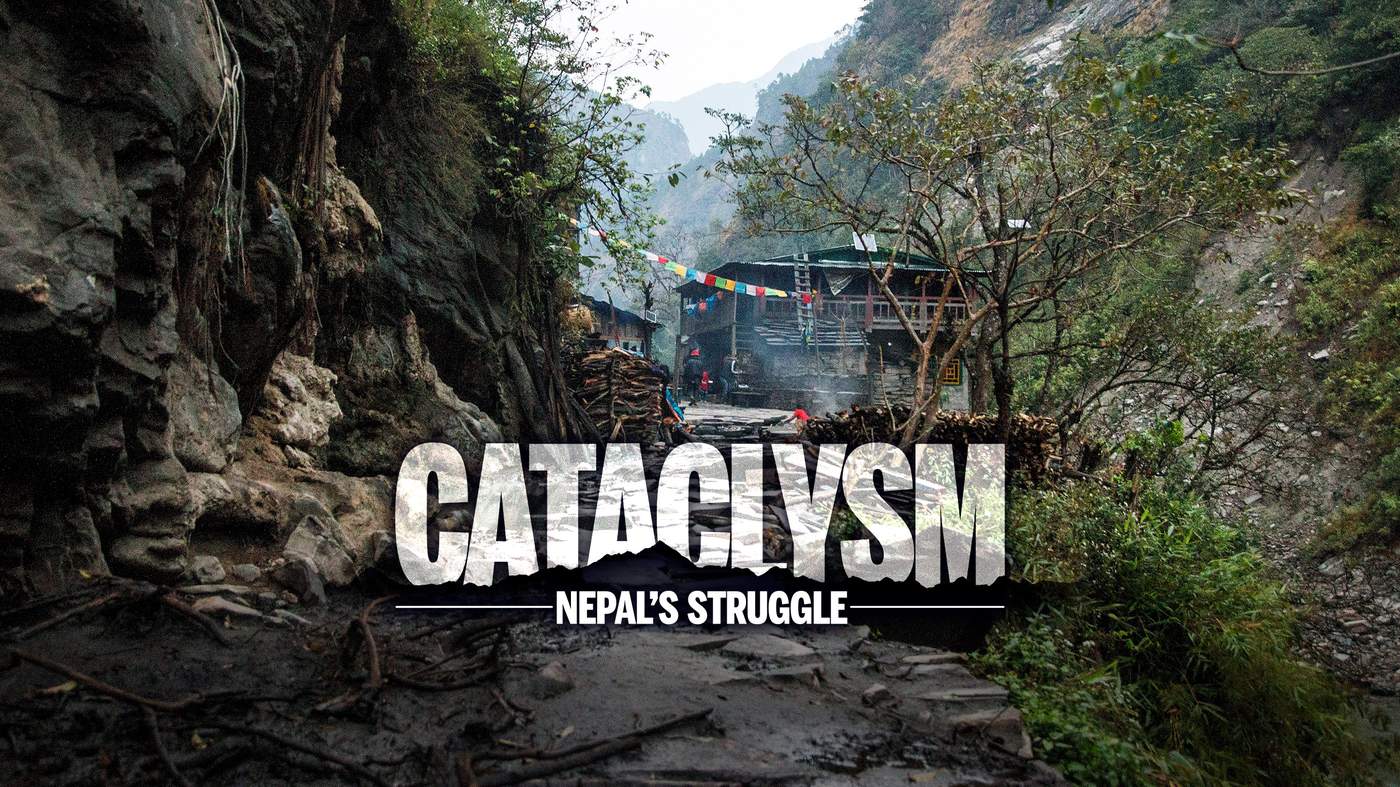

Two years after an earthquake devastated Nepal, people still live in temporary shelters, barely getting by. Kirsty Lawrence and Warwick Smith witness their struggle, after the destruction.

As the earth beneath his feet began to settle, a single thought of family dominated Sukh Gurung's mind: Are you still alive?

Working as a porter, hired to carry bags in Tsum Valley with a group of tourists, all Gurung could do was stand and watch, and worry, as his world collapsed around him.

Sukh Gurung's life has not been the same since the quake.

The 37-year-old walked back to his village through active and unstable landslides, searching for his wife, two sons and daughter.

"We had no idea, was our family alive? Was my house destroyed? I was panicking a lot."

It was almost five days before he found them. They were alive.

Fear turned to relief, but then the real hardship took hold.

Every house in the village had been destroyed, about 100 homes.

It was Gurung’s whole world.

But the village knew no help was coming. They had to help themselves.

"What we did was we took carpet and made a tent out of it," Gurung says.

"For 60 days we stayed in that tent that we made out of carpet."

This small village is like many, with large guest houses for travellers and small unstable-looking shacks for locals.

We ordered noodles and received an apology, they would take an extra 15 minutes as there was no electricity.

Prem Gurung, 36, the owner of the restaurant, said a boulder had taken out their power station during the earthquake, and the government would not fund its repair.

Instead, the community was saving what little money they earned to get the boulder broken down and electricity restored. Its impact was huge.

"At night times it's very hard to serve the guests, because we have limited power supplies with the batteries," Gurung says.

Prem Kumari Gurung's guesthouse at Lapu Besi has had no electricity since the earthquake.

Walking another two hours along winding terrain you stumble across Khorla Bensi.

Arriving at dusk, light switches are flipped. Again, no power.

Our party of eight orders dinner. A wood fire oven is all there is to cook on.

Looking out at the hills you can see where chunks were carved out by the quake.

Buildings around the guest house are missing walls. Bookings are being taken for rooms in partly-constructed buildings.

Quake-damaged buildings are everywhere in Nepal.

Sitting in a white plastic chair on a balcony that creaked as if it doubted its own assembly, guest house owner Kancha Lal Gurung, 46, looks out around the hills and sighs.

He has nowhere else to go.

"I'm staying here only for my business, otherwise there is no point staying out here."

When the earthquake struck, he ran with guests to higher ground, where they stayed for three days.

Eventually, he returned to assess the damage. It was massive.

"I had to renovate everything."

Kancha Lal Gurung stands in front of his guesthouse at Khorla Bensi. The huge slip in the background was caused by the earthquake.

Solar power was installed for main areas, but guest rooms are dark. Posters advertising hot showers still hang, their promise a mirage.

Together, with his three business partners, Gurung says they put in money and took out loans.

But getting back on their feet was difficult, as guest numbers plummeted.

"Before, I used to have an average of eight to 10 guests every day, now sometimes the number is zero."

Money is not his only concern, either. The psychological scars of what happened still remain.

"I still have trauma."

Already-ramshackle buildings were left worse-off following the 2015 earthquake.

Gurung does not expect to get financial help from the government.

"I know I'm not going to get the money.

"Access is a big challenge here, they haven't got here to assess it."

Walking to Khorla Bensi also means walking through active landslide areas, which poses some risk.

Up the trail, about an hour away, is Tatopani, where most trekkers continue onwards to complete the Tsum Valley trek.

However, we headed to the small village of Uhiya, a five-kilometre uphill climb to about 2300 metres.

It's March and bitterly cold, but this isn't even winter.

Houses that were ramshackle even before the earthquake are now a greater shambles.

Looking out across the village of Uhiya there is a sea of tarpaulins, flapping in the crisp wind.

After two years of struggling, this was the hope they had been looking for.

WFP engineering unit business support assistant Rabindra Ojha helped build the trail and says they used local villages to forge it, as they were the ones who would benefit from it.

"Plus, we were offering them employment as well."

Villagers were paid for their time and learned new skills, which could be put to use to gain employment in the future.

The trail has made life significantly easier for locals.

The trail has halved the price of rice in the village.

Gurung says it is improving their quality of life, too.

But she still worries for the safety of her children.

The school suffered extensive damage in the quake, but with no other options, children are still being sent there.

"Sending my children to that building for studies, it doesn't feel safe."

Min Bahadur Sunar teaches a class at Uhiya village.

It was going to cost about 2 million rupees (about NZ$26,900) to fix the schoolhouse, money the village doesn't have and has no sign of raising.

But like the rest of the country, they are just getting on with it, living the best they can in the in-between.

Kirsty Lawrence and Warwick Smith's trip to Nepal was funded by the Asia New Zealand Foundation.